Harold Evans

Sir Harold Evans | |

|---|---|

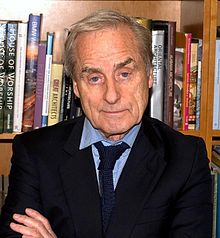

Evans in 2009 | |

| Born | Harold Matthew Evans 28 June 1928 Eccles, England |

| Died | 23 September 2020 (aged 92) New York City, U.S. |

| Nationality | British and American |

| Alma mater | University College, Durham |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Notable credit(s) | The Sunday Times The Week The Guardian BBC Radio 4 |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 5 |

Sir Harold Matthew Evans (28 June 1928 – 23 September 2020) was a British-American journalist and writer. In his career in his native Britain, he was editor of The Sunday Times from 1967 to 1981, and its sister title The Times for a year from 1981, before being forced out of the latter post by Rupert Murdoch.[3] While at The Sunday Times, he led the newspaper's campaign to seek compensation for mothers who had taken the morning sickness drug thalidomide, which led to their children having severely deformed limbs.

In 1984, he and his wife Tina Brown moved to the United States where he became an American citizen, retaining dual nationality. He held positions in journalism with U.S. News & World Report, The Atlantic Monthly, and the New York Daily News. In 1986, he founded Condé Nast Traveller.[4] He wrote books on history and journalism, such as The American Century (1998).[5] In 2000, he retired from positions in journalism to spend more time on his writing. From 2001, he served as editor-at-large of The Week magazine and, from 2005, he was a contributor to The Guardian and BBC Radio 4. Evans was invested as a Knight Bachelor in 2004, for services to journalism. On 13 June 2011, Evans was appointed editor-at-large of the Reuters news agency.[6] From 2013 until 2019, he served as chairman of the European Press Prize jury panel.

Early life and education

[edit]Evans, the eldest of four sons, was born at 39 Renshaw Street, Patricroft, Eccles, to Welsh parents, Frederick and Mary Evans (née Haselum), whom he described in his 2009 memoir as "the self-consciously respectable working class".[3][7] His father was an engine driver, while his mother ran a shop in their front room to enable the family to buy a car.[8] He failed the eleven-plus, needed to gain entry to grammar schools, and attended St Mary's Central School in Manchester and a business school for a year to learn shorthand, a requirement to become a journalist.[9]

Career

[edit]Early career

[edit]Evans began his career as a reporter for a weekly newspaper in Ashton-under-Lyne, Lancashire, at 16. During his national service in the Royal Air Force (1946–1949),[3] he passed an intelligence test to become an officer, but did not hear anything further and served as a clerk.[9] He entered University College, Durham University, after contacting every one of the fourteen universities in Great Britain at the time.[7] While a student, he edited the university's independent newspaper, Palatinate.[10] After studying economics and politics, he graduated in 1952.[3]

Following his appointment as a sub-editor on the Manchester Evening News, he was chosen by the International Press Institute to teach newspaper technique in India.[9] Evans won a Harkness Fellowship in 1956–1957 to travel and study in the United States, spending periods at the universities of Chicago and Stanford.[3][7] After his return, to the UK, he became an assistant editor on the Manchester Evening News.[9] Nicholas Lemann observed that he "joined a long line of British journalists" who did similar studies, from Alistair Cooke to Andrew Sullivan.[7] Evans was appointed editor of a regional daily, The Northern Echo, in 1961.[11] While at the Darlington title, Evans successfully campaigned for cervical smear tests to be remedied so that he could be more available for journalistic work, and he campaigned tirelessly to pardon of Timothy Evans,[12] wrongly convicted and hanged for murders in Notting Hill, London.[13] The Northern Echo was able to demonstrate that there had been a miscarriage of justice.[8]

In 1966, Harold Evans moved to London to become assistant to the editor of The Sunday Times. The owners of the newspaper, the Thomson Organisation, acquired The Times not long afterwards, and Evans' editor, Denis Hamilton was promoted to editor-in-chief of the Times group.[14] He recommended Evans to the board as the next editor of The Sunday Times.[13]

The Sunday Times and The Times

[edit]Reporting

[edit]Evans became editor of The Sunday Times in 1967.[15] Early on during his period as editor came the title's exposure of Kim Philby in that year as a member of the Cambridge Spy ring who had been involved in espionage on behalf of Russia from 1933.[16] Previously it had been claimed that Philby was a low-level diplomat at the time he fled to Moscow in 1963, whereas in actuality, he had been in charge of anti-Soviet intelligence and the chief officer responsible for maintaining contacts with the CIA.[3] Evans was warned the revelations risked national security, receiving a D-notice requesting he should not publish at the beginning of September.[17] Despite this, he went ahead with publication believing the D-notice had been issued to inoculate the government against bad publicity, rather than to maintain the country's security.[8] The official complaint was later withdrawn.[3]

A long-running issue during his tenure was thalidomide, a drug prescribed to expectant mothers suffering from morning sickness, which led to thousands of children in Britain having deformed limbs. They had not received compensation from the drug manufacturers, who in the United Kingdom were the Distillers Company. He organised a campaign by the newspaper's Insight investigative team, appointing Phillip Knightley to run the investigation.[18][19] Evans took on the drug companies responsible for the manufacture of thalidomide, pursuing them through the English courts and eventually gaining victory in the European Court of Human Rights in 1979. The British government was compelled to change the law on contempt of court which had inhibited the reporting of civil cases. While it was legal for the newspaper to campaign, it was not possible for the journalists to report its factual basis. After the ruling in the European Court, the British media was now able to report such cases without restraint.[10][11] The families of thalidomide victims eventually won compensation of £32.5 million as a consequence of Evans' Sunday Times campaign.[19] A documentary about Evans and the thalidomide campaign, Attacking The Devil: Harold Evans and the Last Nazi War Crime, appeared in 2016.[15]

The British government attempted in 1974 to prevent Evans from publishing extracts from the diaries of former Labour cabinet minister Richard Crossman, shortly after Crossman had died and ahead of the diaries publication in book form. Evans risked prosecution under the Official Secrets Act 1911 for breaking the thirty-year rule preventing disclosures of government business. Lord Chief Justice Widgery ruled that publication would not be against the public interest.[13]

Murdoch takeover

[edit]When Rupert Murdoch acquired Times Newspapers Limited in 1981, he appointed Evans as editor of The Times. He remained with the paper only a year, during which time The Times was critical of Margaret Thatcher. Over 50 journalists resigned in the first six months of Murdoch's takeover, a number of them known to dislike Evans. In March 1982, a group of Times journalists called for Evans to resign, despite the paper's increase in circulation, claiming that he had overseen an "erosion of editorial standards".[20] Evans resigned shortly afterwards, citing policy differences with Murdoch relating to editorial independence. Evans included an account of the episode in his book Good Times, Bad Times (1984). In the introduction to the 1994 edition, Evans wrote of Murdoch: "When I come across him socially in New York I find I am without any residual emotional hostility ... I have to remind myself ... that Lucifer is the most arresting character in Milton's Paradise Lost."[21]

On leaving The Times, Evans became director of Goldcrest Films and Television.[13]

Move to the United States

[edit]In 1984, Evans moved to the United States, where he taught at Duke University in North Carolina and Yale University.[3] He was appointed editor-in-chief of The Atlantic Monthly Press and became editorial director of U.S. News & World Report and worked for the New York Daily News. In 1986, he was the founding editor of Conde Nast Traveller where, unlike other publications, the staff were barred from receiving any free travel or hospitality from the organisations they wrote about.[3] Evans was appointed president and publisher of Random House from 1990 to 1997.[22] He acquired rights for $40,000 to the memoir, Dreams from My Father, by Barack Obama, then at the start of his political career.[22]

Evans was editorial director and vice-chairman of U.S. News & World Report, and The Atlantic Monthly from 1997 to January 2000, when he resigned.[23] His work The American Century was published in 1998.[24] The sequel, They Made America (2004), described the lives of some of the country's most important inventors and innovators. Fortune characterised it as one of the best books in the 75 years of that magazine's publication.[25] The book was adapted as a four-part television mini-series that same year and as a National Public Radio special in the US in 2005.[26][27]

Evans became a naturalised United States citizen in 1993.[28] On 13 June 2011, he became editor-at-large at Reuters.[29]

Personal life and death

[edit]In 1953, Evans married fellow Durham graduate Enid Parker, with whom he had a son and two daughters; the marriage was dissolved in 1978.[21] The couple remained on good terms; Enid Evans died in 2013.[30] In 1973, Evans met Tina Brown, a journalist 25 years his junior. In 1974, she was given freelance assignments with The Sunday Times in the UK, and in the U.S. by its Colour magazine.[31] When a sexual affair emerged between the married Evans and Brown, she resigned and joined the rival The Sunday Telegraph. On 20 August 1981, Evans and Brown married at Grey Gardens, in East Hampton, New York, the home of Ben Bradlee, then The Washington Post executive editor, and Sally Quinn.[31] Evans and Brown had a son and daughter.[21]

Evans died in New York City on 23 September 2020 at the age of 92.[3] The cause of death given was congestive heart failure.[32][33]

Honours

[edit]- 1980: Received the Hood Medal of the Royal Photographic Society for photography in public service[34]

- 2000: Named one of International Press Institute's 50 World Press Freedom Heroes of the past fifty years[35]

- 2004: Appointed Knight Bachelor by Queen Elizabeth II for services to journalism[36]

- 2015: Recipient of Kraszna-Krausz Foundation's Outstanding Contribution to Publishing Award[37]

Bibliography

[edit]- Editing and Design: A Five-Volume Manual of English, Typography and Layout (1972) ISBN 0-434-90550-X

- Essential English for Journalists, Editors and Writers (1972) ISBN 0-7126-6447-5[38]

- Newsman's English (1972) ISBN 0-434-90549-6

- Newspaper Design (1973) ISBN 0-434-90554-2

- Editing and Design (1974) ISBN 0-434-90552-6

- Handling Newspaper Text (1974) ISBN 0-03-012041-1

- News Headlines (1974) ISBN 0-03-007501-7

- Downing Street Diary: The Macmillan Years 1957-1963 (1981) ISBN 0-34025-897-7

- Front Page History: Events of Our Century That Shook the World (1984) ISBN 0-88162-051-3

- Good Times, Bad Times (1983) London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson ISBN 0-297-78295-9

- Editing and Design: Book 2: Handling Newspaper Text (1986) ISBN 0-434-90548-8

- Assignments: The Press Photographers' Association Yearbook (Assignments) (1988) by Harold Evans (commentary), Anna Tait (editor) ISBN 0-7148-2501-8

- Makers of Photographic History (1990) ISBN 0-948489-09-X

- Eyewitness 2: 3 Decades Through World Press Photos (1992) ISBN 0-907621-55-4

- Pictures on a Page: Photo-Journalism, Graphics and Picture Editing (1997) ISBN 0-7126-7388-1

- The American Century (1998) ISBN 0-679-41070-8

- War of Words: Memoirs of a South African Journalist (2000) by Benjamin Pogrund, Harold Evans ISBN 1-888363-71-1

- Shots in the Dark: True Crime Pictures (2001) by Gail Buckland, Harold Evans ISBN 0-8212-2775-0

- The Best American Magazine Writing 2001 (2001) Harold Evans (editor) ISBN 1-58648-088-X

- The BBC Reports: On America, Its Allies and Enemies, and the Counterattack on Terrorism (2002) ISBN 1-58567-299-8

- Best American Magazine Writing 2002 (2002) ISBN 1-58648-137-1

- War Stories: Reporting in the Time of Conflict from the Crimea to Iraq (2003) ISBN 1-59373-005-5

- Evans, Harold; Buckland, Gail; Lefer, David (2004). They Made America: From the Steam Engine to the Search Engine: Two Centuries of Innovators. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-27766-2.

- We the People (2007) ISBN 0-316-27717-7

- My Paper Chase: True Stories of Vanished Times (2009) ISBN 978-0-316-03142-4

- Do I Make Myself Clear?: Why Writing Well Matters, New York: Back Bay Books, 2018, ISBN 978-0-316-27717-4[39]

References

[edit]- ^ Emma Youle (14 June 2013), "Obituary: Distinguished Highgate teacher and magistrate Enid Evans dies after a long illness", Ham & High.

- ^ Robert Chalmers (12 June 2010), "Harold Evans: 'All I tried to do was shed a little light'", The Independent.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j McFadden, Robert D. (24 September 2020). "Harold Evans, Crusading Newspaperman With a Second Act, Dies at 92". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ "Remembering Sir Harold Evans, Founding Editor of Condé Nast Traveler".

- ^ A Word on Words; 2719; Harold Evans, December 1998, retrieved 24 September 2020

- ^ "Sir Harold Evans Appointed Reuters Editor-at-Large". Reuters. 13 June 2011. Archived from the original on 22 January 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d Nicholas Lemann, "The Power and the Glory", The New Yorker, 7 December 2009, accessed 3 January 2013

- ^ a b c Hodgson, Godfrey (24 September 2020). "Sir Harold Evans obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d "From the archive: Profile: Harold Evans". New Statesman. 24 September 2020 [1975]. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ a b Luckhurst, Tim (24 September 2020). "Harold Evans was a titan among the greats of British journalism". The Conversation. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ a b Lederman, Marsha (17 April 2015). "Film explores Harold Evans's work to expose the truth about thalidomide". The Globe & Mail. Toronto, Canada. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Mill, The. "The never-ending editor: What drove Harry Evans?". manchestermill.co.uk. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Sir Harold Evans obituary". The Times. London. 24 September 2020. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 24 September 2020. (subscription required)

- ^ Hodgson, Godfrey (24 September 2020). "Sir Harold Evans obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Sir Harold Evans, trailblazing newspaper editor, dies aged 92 from heart failure". The Daily Telegraph. Reuters. 24 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Richard (12 October 2012). "8. British journalism's greatest ever scoops: Philby: I spied for Russia from 1933 (Sunday Times, 1967)". Press Gazette. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Evans, Harold (2009). My Paper Chase: True Stories of Vanished Times: An Autobiography. London: Little, Brown. p. 367. ISBN 9780748114719.

- ^ Sambrook, Richard; Evans, Harold (7 December 2015). "In Conversation with journalist, author and thalidomide campaigner, Harold Evans". The Conversation. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ a b Fay, Stephen (11 December 2016). "He nailed traitors and thalidomide". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 24 September 2020. (subscription required)

- ^ Temple, Mick (2008). The British Press. McGraw-Hill International. p. 67. ISBN 9780335222971.

- ^ a b c Harris, Paul (15 May 2005). "A man of letters". The Observer. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ a b Smith, Harrison (24 September 2020). "Harold Evans, crusading editor on both sides of the Atlantic, dies at 92". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ "Sir Harold Evans, crusading publisher and author, dies at 92". AP NEWS. 24 September 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ "The March of Time". movies2.nytimes.com. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ "The Smartest Books We Know - March 21, 2005". archive.fortune.com. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ "They Made America | Film & More | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ "Book Looks at Inventors and Obscure Geniuses". NPR.org. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ Embedded RealPlayer file BBC News "UK Journalist legend calls it a day", BBC News, 22 October 1999

- ^ Sir Harold Evans Appointed Reuters Editor-at-Large Archived 22 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine Erin Kurtz, Reuters, 13 June 2011

- ^ Youle, Emma (14 June 2013). "Obituary: Distinguished Highgate teacher and magistrate Enid Evans dies after a long illness". Ham & High. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ a b Evans, Harold (2010). My Paper Chase: True Stories of Vanished Times. New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-03142-4.

- ^ Hill, Amelia (24 September 2020). "Thalidomide survivors mourn Harold Evans, their hero and friend". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ "Sir Harold Evans: Crusading editor who exposed Thalidomide impact dies aged 92". BBC News. 24 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Hood Medal of the ROyal Photographic Society. https://rps.org/about/past-recipients/hood-medal/ Archived 19 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 24 September 2020.

- ^ Michael Kudlak, IPI World Press Freedom Heroes: Harold Evans Archived 25 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, IPI Report, June 2000

- ^ United Kingdom: "No. 57155". The London Gazette (1st supplement). 31 December 2003. p. 2.

- ^ "Sir Harold Evans and David Goldblatt recognised by Kraszna-Krausz Book Awards | First Book Award shortlist announced". National Media Museum. 1 March 2015. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ Evans, Harold (2000). "Essential English for journalists, editors and writers". shp2.amsab.be. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ Evans, Harold (2017). "Do I make myself clear? Why writing well matters". shp2.amsab.be. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

External links

[edit]- Sir Harold Evans official website

- Column archive at The Daily Beast

- Column archive at The Huffington Post

- Column archive at The Guardian

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Harold Evans on Charlie Rose

- Harold Evans at The Daily Beast

- Harold Evans collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Harold Evans at Reuters

- Portraits of Harold Evans at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Radio and television programmes

[edit]- BBC Radio 4 – A Point of View 13-week series from 29 July 2005

- Love Letter to America BBC News, 29 July 2005

- BBC audio interview 16 May 2005

- They Made America PBS

- “A Word on Words; 2719; Harold Evans,” 1998-12-01, Nashville Public Television, American Archive of Public Broadcasting

Interviews

[edit]- Harold Evans: They Made America from Bill Thompson's Eye on Books, audio of Harold Evans interview

- The American Century from CNN Book News, 13 November 1998, includes audio clips from Harold Evans

- The American Century Archived 3 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine transcript of Harold Evans interview from PBS NewsHour, 8 June 1999

- Media Giants: Harry Evans profile on Media Circus, July 2007

- Harold Evans Sees Bright Future for Print-on-Demand Newspapers Archived 21 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine from PBS MediaShift, 29 October 2009, interview includes audio clips

- Reuters Editor-at-Large Harry Evans interviews former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and 2012 Republican presidential candidate Jon Huntsman on YouTube, Reuters, 14 June 2011

- 1928 births

- 2020 deaths

- 20th-century American journalists

- 20th-century British journalists

- 20th-century Royal Air Force personnel

- 21st-century American journalists

- 21st-century British journalists

- Alumni of University College, Durham

- American male journalists

- British foreign policy writers

- Deaths from congestive heart failure

- Duke University faculty

- English emigrants to the United States

- English historians

- English male journalists

- English newspaper editors

- English people of Welsh descent

- Foreign policy writers

- The Guardian journalists

- Harkness Fellows

- Knights Bachelor

- Military personnel from Manchester

- Naturalized citizens of the United States

- Palatinate (newspaper) editors

- People from Eccles, Greater Manchester

- People from Newton Heath

- Royal Air Force airmen

- Stanford University alumni

- The Sunday Times people

- The Times people

- University of Chicago alumni