Recruitment to the British Army during World War I

At the beginning of 1914 the British Army had a reported strength of 710,000 men including reserves, of which around 80,000 were professional soldiers ready for war. By the end of the First World War almost 25 percent of the total male population of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland had joined up, over five million men. Of these, 2.67 million joined as volunteers and 2.77 million as conscripts (although some volunteered after conscription was introduced and would most likely have been conscripted anyway). Monthly recruiting rates for the army varied dramatically.

August 1914

[edit]At the outbreak of war on 4 August 1914, the British regular army numbered 247,432 serving officers and other ranks.[1][2] This did not include reservists liable to be recalled to the colours upon general mobilization or the part-time volunteers of the Territorial Force. About one-third of the peace-time regulars were stationed in India[1] and were not immediately available for service in Europe.

For a century British governmental policy and public opinion were against conscription for foreign wars. At the start of World War I the British Army consisted of six infantry divisions,[3] one cavalry division in the United Kingdom formed shortly after the outbreak of the war,[4] and four divisions located overseas. Fourteen Territorial Force divisions also existed, and 300,000 soldiers were in the Reserve Army. Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, considered the Territorial Force untrained and useless. He believed that the regular army must not be wasted in immediate battle, but instead used to help train a new army with 70 divisions—the size of the French and German armies—that he foresaw would be needed to fight a war lasting many years.[3]

British Army medical categories

[edit]All recruits underwent a physical exam by Army medical officers to ascertain whether they would be suitable for military service which used a number and lettering system to categorise the health of each recruit. The following list are the categories used by the British Army in 1914.[5]

- A Able to march, see to shoot, hear well and stand active service conditions.

- A1 Fit for dispatching overseas, as regards physical and mental health, and training

- A2 As A1, except for training

- A3 Returned Expeditionary Force men, ready except for physical condition

- A4 Men under 19 who would be A1 or A2 when aged 19

- B Free from serious organic diseases, able to stand service on lines of communication in France, or in garrisons in the tropics.

- B1 Able to march 5 miles, see to shoot with glasses, and hear well

- B2 Able to walk 5 miles, see and hear sufficiently for ordinary purposes

- B3 Only suitable for sedentary work

- C Free from serious organic diseases, able to stand service in garrisons at home.

- C1 Able to march 5 miles, see to shoot with glasses, and hear well

- C2 Able to walk 5 miles, see and hear sufficiently for ordinary purposes

- C3 Only suitable for sedentary work

- D Unfit but could be fit within 6 months.

- D1 Regular Royal Artillery (RA), Royal Engineers (RE), infantry in Command Depots

- D2 Regular RA, RE, infantry in Regimental Depots

- D3 Men in any depot or unit awaiting treatment

Examinations

[edit]Medical examinations were conducted in a very specific way according to War Office Instructions issued within the Regulations for the Medical Services of the Army, the Regulations for Recruiting, and the regulations for the Territorial Force on 1 August 1914. Basic requirements for a recruit was that their height, weight, chest measurement and age all correlated with a standard table. Medical examiners were given the discretion to decide a recruit's "apparent age," based on their appearance and physical stature, when they did not bring satisfactory documentation for proof of age.[6]

Detailed body examinations would include looking for signs of sexually transmitted diseases, vaccination marks, lesions and rashes; the scrotum and anus would also be checked; there would be a stethoscopic examination of the heart, lung and abdomen; the hands and feet, elbows and knees would be studied for lameness, weakness and deformities; teeth (for loss and decay as being unable to chew because of poor oral hygiene was a common cause for failing the medical examination); eyesight and hearing.[6]

Aside from the physical tests, examiners would also the note the intelligence, voice, and character of the recruit in response to questions they would ask him. This would be used to create a psychological profile that would help determine the fitness of the candidate.[6]

Medical rejections and deferments

[edit]There were numerous medical reasons why recruits might be deemed unfit for service.[6]

- Any signs or symptoms of tuberculosis

- Syphilis

- Any respiratory tract infections

- Palpitations or heart disease

- Generally impaired constitution

- Poor eyesight

- Hearing loss

- Stammering

- Tooth decay that inhibited eating

- Deformity of chest or joints

- Abnormal curvature of spine

- Intelligence

- Hernia

- Haemorrhoids

- Varicose veins or varicocele

- Chronic skin conditions

- Chronic ulcers

- Fistula

- Any other disease or physical defect that would prevent military service

Volunteer Army, 1914–15

[edit]

In 1914, the British had about 5.5 million men of military age, with another 500,000 reaching the age of 18 each year.[8][page needed] The first call was for 100,000 volunteers, made on 11 August, followed by another 100,000 on 28 August.[9] By 12 September, almost half a million men had enlisted. At the end of October, 898,005 men had enlisted,[10][11] of whom approximately 640,000 were non-TF enlistments.[12][13] Around 250,000 underage boys also volunteered, either by lying about their age or giving false names. These were always rejected if the lie was discovered.[14]

The standard Regular terms of service in the British Army were 7 years service with the colours, and 5 years in the reserve. To facilitate recruitment, supplementary Regular terms of service were announced by Army Order 296 dated 6 August 1914. Recruits to the New Army could serve for “three years or the duration of the war, whichever the longer”. These "General Service" terms were changed by Army Order 470 dated 7 November, simplified to "the duration of the war." The recruit had the right to choose the regiment they joined.[15]

To address the short-term need for trained men to replenish the originally deployed BEF units, supplementary Special Reserve terms of service were announced by Army Order 295 dated 6 August 1914, rescinded 7 November 1914. Ex-military men could reenlist for “one year or the duration of the war, whichever the longer”.[16]

It was believed that former NCOs may be reticent to reenlist, having to serve as Privates. Given the need not only for former privates to enlist, but also experienced NCOs to play a part in the expansion of the army, Army Order 315 dated 17 August 1914 clarified matters. It states that 'an ex-non-commissioned officer of the regular army who enlists [under the supplemental terms of service announced on 6 August 1914].. [will be] promoted forthwith to the rank held on discharge.'[8][page needed]

One early peculiarity was the formation of 'pals battalions': groups of men from the same factory, football team, bank or similar, joining and fighting together. The idea was first suggested at a public meeting by Lord Derby. Within three days, he had enough volunteers for three battalions. Lord Kitchener gave official approval for the measure almost instantly and the response was impressive. Manchester raised nine specific pals battalions (plus three reserve battalions); one of the smallest was Accrington, in Lancashire, which raised one. One consequence of pals battalions was that a whole town could suffer a severe impact on its military-aged menfolk in a single day of fierce battle.[17][page needed]

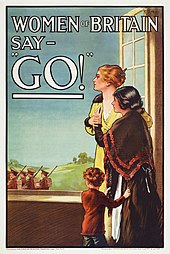

The women's suffrage movement was sharply divided, the slight majority becoming very enthusiastic patriots and asking their members to give white feathers (the sign of the coward) in the streets to men who appeared to be of military age to shame them into service. After assaults became prevalent the Silver War Badge was issued to men who were not eligible or had been medically discharged.

The available pool was diminished by roughly 1.5 million men who were "starred": kept in essential occupations. Almost 40 percent of the men who volunteered were rejected for medical reasons. Malnutrition was widespread in U.K. society; working class 15‑year‑olds had an average height of only 5 feet 2 inches (157 cm) while the upper class was 5 feet 6 inches (168 cm).[19][page needed]

From the start Kitchener insisted that the British must build a massive army for a long war, arguing that the British were obliged to mobilise to the same extent as the French and Germans. His goal was 70 divisions, and the Adjutant General asked for 92,000 recruits per month, well above the number volunteering (see the graph). The obvious remedy was conscription, which was a hotly debated political issue. Many Liberals, including Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, were ideologically opposed to compulsion, but by 1915 they were wavering.

15 July 1915 the National Registration Act was passed by the British Government, exactly one month later there was a census of every citizen aged 15 to 65, approximately 29 million forms completed.[20] A pink coloured registration card was issued to each registree, listing pertinent data.[21] These records were ordered to be destroyed in 1921, yet some did survive, including the lately discovered forms of 2,409 women living in Cirencester, since transcribed and made publicly available.[22]

The Cabinet were given a strong warning in September 1915 in a paper presented by their only Labour member, Minister of Education Arthur Henderson.[23] He argued many working men would strongly resist serving a nation in which they did not have a legitimate share in governing. They resented the idea of being dragooned to face possible death by a Parliament they had no part in electing—forty percent of men over 21 were denied the vote by the franchise and registration laws (until the Representation of the People Act of 1918). To them conscription was yet another theft of working men's rights by rich capitalists. The only counter-argument the Government could offer was it was of absolute necessity. Workers must be convinced that there were too few volunteers to meet the need, meaning the loss of the war and the end of Britain! Army leaders should convince Union leaders by stating military facts. Henderson's own son was killed in the war a year later.[24]

The Derby Scheme

[edit]

The Derby Scheme was launched in Autumn 1915 by the Earl of Derby, Kitchener's new Director General of Recruiting, to determine how many new recruits could be signed up, using appointed canvassers visiting eligible men at home to persuade them to 'volunteer' for war service.[25][26]

The scheme announcement caused an initial rise in recruitment, as some preferred to go to the recruiting office rather than wait for the inevitable. The process began with each eligible man's registry card, from the August 1915 National Registry, being copied onto another card which was sent to his local constituency's Parliamentary recruiting committee. This Committee appointed 'canvassers' who they considered "tactful and influential men", and not themselves liable for service, to visit the men in their homes.[27] Many canvassers were experienced in politics, though discharged veterans and the fathers of serving soldiers proved the most effective, while some just used threats to persuade. Although women were not allowed to canvas, they did contribute by tracking men who had moved address.[28][failed verification]

Every man would be given a copy of a letter from the Earl of Derby, explaining the programme and stating that they were in "a country fighting, as ours is, for its very existence".[29][failed verification] and had to state whether or not he was willing to attest to enlist.

Those who did agree to attest had to promise to present themselves at their recruiting office within 48 hours, while some were accompanied there immediately. If they passed a medical examination, they were sworn in and paid a 'signing bonus' of 2s 9d. The next day they were transferred to Army Reserve B. A khaki armband bearing the Royal Crown [30] was provided to all who had enlisted, or officially rejected, as well as to starred and discharged men. (This ceased once conscription was introduced, Jan.1916).

The enlistee's data was copied onto another card and used to assign him to one of 46 married or unmarried age groups, and promised that only entire groups would be called for active service, after 14 days prior notice. Single men's groups would be called before married, any who wed after the day the scheme began were still classified as single. Married men were assured their group would not be called if too few single men attested – unless conscription was introduced.

The scheme was undertaken during November–December 1915 and obtained 318,553 medically fit single men.[31] However, 38% of single men and 54% of married men had resisted the orchestrated pressure to enlist in the war, so the British Government, determined to ensure a supply of replacements for mounting casualties overseas, instead passed The Military Service Act of compulsory conscription, 27 January 1916.[32]

Conscription 1916–1918

[edit]As there were too few volunteers to fill the ranks, the Military Service Bill was introduced in January 1916, with compulsory conscription for the first time in Britain's history. Every unmarried man and childless widower between 18 and 41 was offered three choices:

- Enlist at once.

- Attest at once under Derby's system.

- Or on 2 March 1916 be automatically deemed to have enlisted.

In May 1916 the bill was extended to married men and in April 1918 the upper age was raised to 50 (or 56 if need arose). Ireland was excluded due to the 1916 Easter Uprising, yet many Irish men still volunteered to enlist.[32]

One of the immediate effects of conscription was the biggest protest demonstration Britain had seen since the 1914 anti-war protests.[33] Thousands marched from London's East End to Trafalgar Square, where they listened to speeches from Sylvia Pankhurst and a Glasgow councillor who reported that engineers had come out on strike along the Clyde. The event ended in violence when a group of soldiers and sailors charged the crowd, ripped their banners and threw dye in their faces. Some of the assailants were arrested, but Bow Street magistrates let them off with nominal fines and a warning to "leave these idiots alone in future".[34]

As Arthur Henderson had warned, compulsion was unpopular, by July 1916, 93,000 (30%) of those called up for military service had failed to appear (In reality they had little chance of escape, although a lucky few were hidden by sympathisers) [35][page needed] and 748,587 had claimed an exemption – the men, or their employers, could appeal to a civilian Military Service Tribunal in their district on the grounds of work of national importance, business or domestic hardship, medical unfitness or conscientious objection.[36][37] Dealing with these cases filled the judicial courts, although the standards of appeal tribunals were dubious: in York a case was determined in an average of eleven minutes, while two minutes was typical at Paddington, London.[38] In addition to those objecting to enlisting, there were 1,433,827 already starred as being in a war occupation, ill or already discharged from service due to illness; the enforced conscription act ultimately failed to satisfy Government demand for lives.[15]

Although it has been the focus of the tribunals' image since the war, only two percent of those appealing were conscientious objectors. Around 7,000 of them were granted non-combatant duties, while a further 3,000 ended up in special work camps. 6,000 were imprisoned. Forty-two were sent to France to potentially face a firing squad. Thirty five were formally sentenced to death, but immediately reprieved, with ten years penal servitude substituted.

Many of those appealing were given some kind of exemption, usually temporary (between a few weeks and six months) or conditional on their situation at work or home remaining serious enough to warrant their staying at home. In October 1916 1.12 million men held tribunal exemption or had cases pending,[40] by May 1917 this had fallen to 780,000 exempt and 110,000 pending. At this point 1.8 million men were exempted, more men than were serving overseas with the British Army.[41][failed verification] Some men were exempted on the condition that they joined the Volunteer Training Corps for part-time training and home defence duties; by February 1918, 101,000 men had been directed to the Corps by the tribunals.[42]

A newspaper report on 17 February 1916 listed five sample appeals for exemption from conscription, and their results.[43][failed verification]

| Appealer(s) | On behalf of | Plea | Result of plea |

|---|---|---|---|

| a firm of art dealers | their clerk | busy with a big export trade | appeal rejected |

| Royal Academy | W. R. H. Lamb (its secretary) | busy with 12,000 incoming works; no available replacement | his conscription was delayed 3 months |

| a tobacco and cigarette manufacturers | their blender | "we supply army officers" | appeal rejected |

| Oswald Stoll | J. P. Seaborn (artist and photographer) | busy making images, etc. for Mr. Stoll's theatres | wait while accumulating a list of about 40 appealed employees |

| Mr. Brenman (clog dancer, member of the music hall act Five Dorinos) | needed to hold group together | his conscription was delayed 1 month | |

In 1917 the Commons passed a bill to give the vote to all males over 21 (and to many women as well), but it did not become law until 6 February 1918. In the same month occupational exemptions were withdrawn for men 18 to 23, in October 1918 there were 2,574,860 men in reserved occupations. Men aged 18½ were sent to the fronts starting in March 1918, violating a pledge to keep them safe until 19. There were also problems with men's suitability for active service. The healthy manpower was simply not there – recruits were sorted into three classes, A, B, and C, in order of fitness for front-line service. In 1918, 75 percent were classed as A, some B men also had to be sent into the trenches.

The upper limit on the number of men conscripted is usually calculated by assuming that all recruits after 1 March 1916 were conscripts: 1,542,807 men, 43.7% of those who served in the Army during the war. However, Derby had enlisted 318,553 single men in Special Reserve B, who were called up in spring 1916, which reduces the conscripted to 37%. The married men who had attested in the Derby plan are harder to categorize because they were not called up from the Reserve but swept up with the rest. It seems that somewhat less than 35% of the men in the army were compelled to serve.

Ireland

[edit]In 1918, legislation intended to extend conscription to Ireland was opposed by a broad movement of Irish nationalists and the Catholic Church in Ireland. The central role of Sinn Féin in this movement boosted its popularity in the buildup to the November general election.

Advertising for recruitment

[edit]

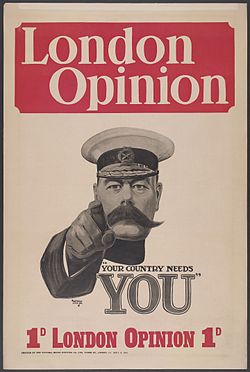

Official advertising for recruits was in the control of the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee (PRC), but private efforts such as that by the London Opinion with the now iconic image of Kitchener were also produced. Posters were prepared in different sizes according to where they would be used; two sizes 40 and 20 by 15 in (1,020 and 510 by 380 mm) were common. The PRC was formed of the Prime Minister and heads of political parties later joined by other representatives such as for the Trades Union Congress; its sub-committees handled the preparation and publishing of recruiting materials.

Over the course of the war the PRC was responsible for 164 poster designs and 65 pamphlets. Between those and other advertising materials a total of over 54 million pieces were produced at a cost of £40,000. According to numbers of posters produced, the most popular official PRC posters were:

- "Lord Kitchener", 1915. Posters No. 113 and 117, 145,000 copies

- "Remember Belgium", 1914–1915. PRC16 and PRC 19, a British soldier on guard while a woman flees her burning home. 140,000 copies

- "Take Up The Sword of Justice", September 1915 PRC 105, 106, 11. By Bernard Partridge featuring the sinking of the Lusitania in the background with a figure offering a sword, 105,000 copies

- "Serve The Guns" May 1915. PRC 85a, 85b, 85c. Soldier and munitions worker shaking hands. 101,000 copies

- "He did his duty. Will You do Yours". December 1914. PRC 20. Portrait of Lord Roberts (who had recently died of pneumonia after visiting Indian troops on the Western Front) with his Victoria Cross. 95,000 copies.

The "King's Message" reprinted in poster form ran to 290,000 copies.[44][page needed]

Recruiting staff

[edit]Notable men who served as army recruiters during the war included:

- Sergeant John Doogan, Victoria Cross recipient

- Captain Samuel Hoare, later intelligence officer and Conservative politician

- Major Lionel Nathan de Rothschild, banker and Conservative MP (awarded OBE for his services)

See also

[edit]- Monthly recruiting figures for the British Army in the First World War

- British Army First World War reserve brigades

- Conscription in Australia

- Conscription Crisis of 1917 in Canada

- Compulsory military training in New Zealand

- No-Conscription Fellowship

- Opposition to World War I

- Temporary gentlemen

References

[edit]- ^ a b Chandler 1996, p. 211.

- ^ SMEBE 1922, p. 30

- ^ a b Tuchman 2014, pp. 231–233.

- ^ Becke 1935, p. 6.

- ^ "British Army Medical Categories 1914". www.eehe.org.uk. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d Baker, Chris. "Instructions for the physical examination of recruits". Retrieved 15 August 2022 – via The long, long trail.

- ^ "the Museum of New Zealand's description of the poster". Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ a b Simkins 2007.

- ^ Rinaldi 2008, p. 16.

- ^ SMEBE 1922, p. 364

- ^ "Enlistments [bar chart] Regular Army and TF 1914-1918". BEF 1915: Loos and the Kitchener battalions. Great War Forum. 8 January 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

SMEBE has monthly recruiting data for Regs and TF combined for the whole war (shown in the chart below). I wonder how long it took for the casualty data to hit home? The dates for Loos run into mid October, so allowing for a few weeks for the casualty numbers to filter back, it is possible that the full impact was not absorbed by the public until mid to late November?

- ^ Simkins, Peter (29 January 2014). "Voluntary recruiting in Britain, 1914-1915". The British Library. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ "Recruiting [bar charts] Aug-Dec 1914". BEF 1915: Loos and the Kitchener battalions. Great War Forum. 8 January 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

I recall late Sep 1914 that the authorities tightened up the requirements in order to put the brakes on recruiting, only to relax it again in Nov 1914, once the backlog had started to clear. The effects can be clearly seen in the daily data (see below). The subtle changes in the recruiting criteria are of great interest. Sadly I only have daily recruiting data for 1914 [within "New Armies: Organisation", archive reference WO 162/3]. Thereafter it becomes monthly.

- ^ "How did Britain let 250,000 underage soldiers fight in WW1?". iWonder. BBC. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ a b Baker, Chris. "Enlisting into the army". Retrieved 15 August 2022 – via The long, long trail.

- ^ Langley Pt2 2014, p. 29.

- ^ Gregory 2007.

- ^ SMEBE 1922, p. 364

- ^ Floud 1990.

- ^ "General Register Office: National Registration: Correspondence and Papers".

- ^ Beckett 1990, p. 4–13.

- ^ "The National Registration Act 1915". Gloucestershire Archives – via www.gloucestershire.gov.uk.

- ^ Arthur Henderson (7 September 1915). Manpower and conscription (pdf) (Report). Cabinet Office. CAB 37/134/5 – via The National Archives UK.

- ^ "Captain David Henderson: Labour Party leader's son on the Somme". www.thehistorypress.co.uk.

- ^ Baker, Chris. "The Group System (Derby Scheme)". Retrieved 15 August 2022 – via The long, long trail.

- ^ "Lord Derby's plain words". General News. The Times. No. 41002. London. 3 November 1915. col C, p. 7.

In the Recruiting Supplement which is presented free with to-day's issue of The Times will bo found a letter in which Lord Derby explains in further detail the conditions by which the success of his recruiting scheme will be judged.

- ^ "Attitudes Towards Conscription". WW1 East Sussex. 20 June 2017.

- ^ Manchester Guardian October and November 1915.

- ^ Times (London) Special Supplement, 3 November 1915 p. 3.

- ^ "The Derby scheme, crown armband". www.photodetective.co.uk.

- ^ Manpower available for HM Forces (pdf) (Report). Cabinet Papers. Cabinet Office. 1 January 1916. CAB 37/140/1 – via The National Archives UK.

- ^ a b "Conscription WW1". www.parliament.uk.

- ^ Richard Norton-Taylor (14 May 2014). "Ignore the propaganda, conscription was not so popular". The Guardian. Defence and security blog.

- ^ Andy McSmith (16 May 2014). "Britain introduces conscription when the appeal to patriotic sentiment was no longer enough". The Independent. A History of the First World War in 100 moments.

- ^ Rippon 2009.

- ^ "Conscription and Conscientious Objection – History of government". history.blog.gov.uk. 30 September 2014.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, p. 152.

- ^ Beckett 1990, p. 7.

- ^ SMEBE 1922, p. 228-231

- ^ "Derby scheme: Statement of the War Committee, 24 October 1916". Army recruiting: Derby scheme (paper) (Report). Records of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Cabinet Office. 1916. CAB 17/158 – via The National Archives UK.

- ^ SMEBE 1922

- ^ Beckett 1990, p. 31.

- ^ Daily Telegraph Thursday 17 February 1916, reprinted in Daily Telegraph Wednesday 17 February 2016 page 26

- ^ Taylor 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Becke, Major A. F. (1935). Order of Battle of Divisions Part 1. The Regular British Divisions. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-1-871167-09-2.

- Beckett, Ian (1985). A Nation in Arms: A Social Study of the British Army in the First World War. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-1737-7. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- Beckett, Ian (1990). "The Real Unknown Army; British Conscripts, 1916-1919". In Becker, Jean-Jacques; Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane (eds.). Les Societes Europeennes et la Guerre de 1914-1918. Nanterre: Publications de l'Université de Nanterre. ISBN 978-2-95-042550-8.

- Bowman, Timothy; et al., eds. (2020). The disparity of sacrifice : Irish recruitment to the British armed forces, 1914-1918. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-78-962185-3.

- Chandler, David (1996). The Oxford History of the British Army. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-285333-3.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-185-5.

- Floud, Roderick; et al., eds. (1990). Height, Health, and History: Nutritional Status in the United Kingdom, 1750–1980. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-130314-9.

- Gregory, Adrian (2007). The Last Great War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Langley, David (September 2014). "British Line Infantry Reserves for the Great War - Part 2". Stand To! (101). The Western Front Association: 27–31.

- Rinaldi, Richard A (2008). Order of Battle of the British Army 1914. Takoma Park, Maryland: Tiger Lilly Books. ISBN 978-0-9776072-8-0.

- Rippon, Nicola (2009). The Plot to Kill Lloyd George: The Story of Alice Wheeldon and the Peartree Conspiracy. Wharncliffe Books. ISBN 978-1-84563-079-9.

- Simkins, Peter (2007). Kitchener's Army: The Raising of the New Armies, 1914–16. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84-415585-9.

- Taylor, James (2013). Your Country Needs YOU - The Secret History of the Propaganda Poster (ebook). Salford, Manchester: Saraband. ISBN 978-1-90-864311-7.

- Tuchman, Barbara W. (2014) [1962]. Guns of August. Random House Trade. ISBN 978-0-345-38623-6.

- Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War. 1914–1920. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 1922.

External links

[edit]- The British Army in the Great War

- Collection of World War I Recruiting Posters issued by the British Army in the Library of Trinity College Dublin