Minneapolis Institute of Art

| |

Mia viewed from the north | |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

| Established | 1883 |

|---|---|

| Location | 2400 Third Avenue South Minneapolis, Minnesota |

| Coordinates | 44°57′31″N 93°16′27″W / 44.95861°N 93.27417°W |

| Collection size | 90,000+ |

| Visitors | 591,069 (2022)[1] |

| Director | Katherine Luber |

| Public transit access | metrotransit Bus: 11B, 11C, 17, 18 |

| Website | artsmia.org |

The Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia) is an arts museum located in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. Home to more than 90,000 works of art representing 5,000 years of world history, Mia is one of the largest art museums in the United States. Its permanent collection spans about 20,000 years and represents the world's diverse cultures across six continents. The museum has seven curatorial areas: Arts of Africa & the Americas; Contemporary Art; Decorative Arts, Textiles & Sculpture; Asian Art; Paintings; Photography and New Media; and Prints and Drawings.

Mia is one of the largest arts educators in Minnesota. More than a half-million people visit the museum each year, and a hundred thousand more are reached through the museum's Art Adventure program for elementary schoolchildren. The museum has a free general admission policy, as well as public programs, classes for children and adults, and interactive media programs.[2]

History

[edit]

The Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts was established in 1883 to bring the arts into the life of the community. This group, made up of business and professional leaders, organized art exhibits throughout the decade. In 1889, the Society, now known as the Minneapolis Institute of Art, moved into its first permanent space, inside the newly built Minneapolis Public Library.

The institute received gifts from Clinton Morrison and William Hood Dunwoody, among others, for its building fund. In 1911, Morrison donated the land, formerly occupied by his family's Villa Rosa mansion, in memory of his father, Dorilus Morrison, contingent on the institute's raising the $500,000 needed for the building. A few days later, the institute received a letter from Dunwoody, who got the ball rolling: "Put me down for $100,000." A fundraising dinner a few days later brought in $335,500, donated in 90 minutes.[3]

The new museum, designed by the firm of McKim, Mead and White, opened in 1915. The building came to be recognized as one of the finest examples of the Beaux-Arts architectural style in Minnesota. The art historian Bevis Hillier organized the exhibition Art Deco at the museum, presented from July to September 1971, which caused a resurgence of interest in this style of art. The building was originally meant to be the first of several sections, but only the front piece was built. Several additions have been built to other plans, including a 1974 addition by Kenzo Tange. An expansion designed by the 2012 Driehaus Prize winner Michael Graves was completed in June 2006. Before the latest expansion, just 4 percent of the museum's nearly 100,000 objects could be on view at the same time; now that figure is 5 percent.[4][5] Target Corporation, for which the new wing is named, was the biggest donor, with a lead gift of more than $10 million.[4]

In 2015, the institute rebranded itself, dropping the final "s" from its name, to become the Minneapolis Institute of Art and encouraging the use of the nickname Mia instead of the acronym MIA.[6][7]

Kaywin Feldman became director and president of the institute in 2008. During her tenure, attendance doubled, digital access was emphasized, and social justice and equity programs were adopted. In December 2018, she was named to be the next director of the National Gallery of Art took that office in March 2019.[8][9]

In October 2019, Katherine Luber, formerly of the San Antonio Museum of Art, was named as the new director and president of Mia.[10]

In January 2024, Robert Cozzolino, a curator who had garnered praise for spotlighting underrepresented artists, was fired. This decision prompted accusations that the museum has become “a toxic environment for people of color” under Luber's leadership. Over 450 members of the city’s art community, including David Lynch and Dyani White Hawk, signed an open letter of support in response to the Cozzolino's firing.[11][12][13]

Collection

[edit]The museum features an encyclopedic collection of approximately 80,000 objects[14] spanning 5,000 years of world history. Its collection includes paintings, photographs, prints and drawings, textiles, architecture, and decorative arts. There are collections of African art, art from Oceania and the Americas, and an especially strong collection of Asian art, called "one of the finest and most comprehensive Asian art collections in the country".[15] The Asian collection includes Chinese architecture, jades,[16] bronzes, and ceramics.[15]

The institute owns the Purcell-Cutts House, just east of Lake of the Isles. The house was designed by Purcell & Elmslie and is a masterpiece of Prairie School architecture. It was donated to the museum by Anson B. Cutts Jr., the son of its second owner. The house is available for tours on the second weekend of each month.[17][18]

Services

[edit]

In order to encourage private collecting and assist in the acquisition of important works of art, the museum has created "affinity groups" aligned with the seven curatorial areas of the museum. The groups schedule lectures, symposia, and travel for members.

The museum features a regular series of exhibitions that bring in traveling collections from other museums for display. Local business partners fund many of these exhibitions, and some feature the artists leading public tours through the exhibition.

The museum houses the Minnesota Artists Exhibition Program, an artist-controlled program devoted to the exhibition of works by artists who live in Minnesota.[19]

The Museum Library contains more than 60,000 volumes on art and art history. The library is open to the public.[20]

Outdoor exhibits

[edit]The institute has a number of exhibits outside the building.[21] A pair of Chinese lions sit on either side of the 24th Street entrance. They were a gift from Ella Pillsbury Crosby in 1998. Because a museum curator determined that it would be too difficult to export 18th-century statues, new ones were carved in China in the 18th century style.[22]

The bronze statue The Fighter of the Spirit, by Ernst Barlach stands near the 24th Street entrance. The statue shows a winged man holding a sword vertically, tip up, and standing on the back of a snarling beast. The statue was commissioned by the University of Kiel and was originally placed in front of its church (Holy Spirit Church). The statue did not fit with the ideals of the ruling National Socialist party; it was vandalized and condemned as degenerate art. As a result, the statue was removed and cut into four pieces, in preparation for melting down. However, the pieces were hidden on a farm and didn't resurface until 1946. The statue was repaired and placed in front of the Church of St. Nicholas (the Holy Spirit Church having been destroyed during the war).[23][24] Two copies of the statue were made at this time; the MIA acquired one copy in 1959; the other is in front of the Gethsemane Church in Berlin.[25][26]

The Chinese Garden, which can be seen from inside the café, contains Taihu stones. These stones are said to represent the mountains of the Buddhist and Taoist immortals.[21] The garden was a gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton.[27]

Target Park, which sits behind the museum, contains several contemporary statues, including an untitled work in bronze (c. 1968) by Pietro Consagra, Samba in African granite (1993) by Richard Erdman, and L'arbre de vie in stainless steel and pigment (20th century), designed by Jean Willy Mestach and manufactured by Michael Chowen.[28] There is also a granite and steel pavilion entitled Labyrinth (1993) by John Willenbecher. There are wide lines cut into the steel roof of the pavilion so that when the viewer stands inside, the labyrinth can be viewed by looking up.[21][29]

To celebrate its 100th anniversary, the institute purchased a sculpture by the Polish artist Igor Mitoraj (1944–2014). Eros Bendato Screpolato, 1999, is one of a series of bronze "bandaged heads" produced by Mitoraj. Similar Mitoraj sculptures can be found at other public sites, including Market Square in Kraków, Poland, and Citygarden in downtown St. Louis, Missouri.[30][31][32]

Management

[edit]Finances

[edit]

The William Hood Dunwoody Fund, endowed with one million dollars when Dunwoody died in 1914, has been used to purchase thousands of works.[33] Bruce Dayton, a life trustee of the institute since 1942, insisted that money raised in the $100 million fund-raising campaign for the Target wing, which opened in 2006, be split evenly between the building and the acquisitions endowment. That fund, now at $91 million, has allowed the institute to buy a rare early 18th-century Native American painted buckskin shirt and a nine-foot-long topographical View of Venice made by Jacopo de' Barbari in 1500, among other recent purchases.[34] In 2009, the value of the museum's $145 million endowment had fallen 21 percent from January 2008. The endowment typically provides nearly one-fifth of operating revenues. Contributions from individuals, corporations and foundations account for a quarter of revenues,[35] Almost half of the museum's operating money comes from the "park-museum fund," a century-old Hennepin County tax dating to 1911 that provides public support in exchange for free admission. That fund, which has risen steadily in recent years, provided the museum $12.6 million in the fiscal year of 2010. In 2011, the museum's annual budget was at $24.6 million, and endowment income was a total $4.3 million.[36]

In August 2016, the institute announced a $6 million bequest to fund the Gale Asian Art Initiative, which is designed to highlight the museum's holdings in Asian art, estimated at 16,800 objects. The bequest was made by Alfred P. Gale, an heir to the Pillsbury flour fortune. The first exhibition of the initiative will be Ink Unbound: Paintings by Liu Dan. Liu Dan, a contemporary Chinese artist has been asked to create an ink painting based on a painting in the museum's collection. Dan chose St. Paul and St. Barnabas at Lystra, a 17th-century painting by the Dutch artist Willem de Poorter.[37]

In popular culture

[edit]Scenes from the 1982 film The Personals were filmed in the museum, and Chuck Close's "Frank" and Max Beckmann's "Blind Man's Buff" were featured.[38]

Restitution claims

[edit]In 2008, the museum restituted Fernand Leger’s “Smoke Over Rooftops” to the heirs of Jewish collector Alphonse Kann whose collection had been looted by Nazis. The painting had passed through the Buchholz Gallery in New York in 1951.[39][40]

In April 2024, the Italian Ministry of Culture ordered a ban on loans to the museum due to a legal dispute regarding the provenance of the Stabiae Doriforo, a Roman-era copy of the ancient Greek sculpture The Doryphoros of Polykleitos, which Italy said was looted from Stabiae and was subsequently bought by the museum from a private dealer in 1986.[41]

Selected objects & paintings

[edit]-

Imperial Portrait of a Prince, China, Qing dynasty

-

Ceremonial vessel, central Thailand, c. 1000-300 BCE,

-

Pair of winged dragons, China, Warring States period

-

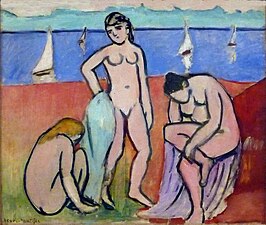

Henri Matisse, Les trois baigneuses (Three Bathers), 1907

-

El Greco, Cleansing of the Temple, 1571

-

Ceramic Bowl Fish, Mimbres, c. 1050-1150

-

Jean Siméon Chardin, The Attributes of Art, 1766

-

Joan Miró, Les cartes espagnoles (The Spanish Playing Cards), 1920

-

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees Saint-Rémy, November 1889

-

Rembrandt's Lucretia, 1666

-

Ainu attush robe, Hokkaido, Japan, 19th

-

Paul Gauguin, Under the Pandanus II, 1891

-

Fernand Léger, Le compotier (Table and Fruit), 1910–11

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Minneapolis Star-Tribune, December 30, 2022

- ^ "Minneapolis Institute of Art". New.artsmia.org. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Gihring, Tim (January 1, 2015). "Mia Stories". Minneapolis Institute of Art. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ a b Tillotson, Kristin (June 9, 2006). "Minneapolis Institute of Arts Opens New Wing". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Wurzer, Cathy (June 7, 2006). "Minneapolis Institute of Arts Opens New Wing". Mprnews.org. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "MIA reboots brand to become 'Mia'". Mprnews.org. August 10, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Tim Gihring (August 3, 2015). "Once at Mia: What's in a name? — Minneapolis Institute of Art". New.artsmia.org. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Kerr, Euan, "Mia's director will leave to head National Gallery", Minnesota Public Radio News, December 11, 2018.

- ^ McGlone, Peggy, "The National Gallery of Art will have a female director for the first time in its history", The Washington Post, December 11, 2018.

- ^ Sheets, Hilarie M. (October 1, 2019). "A New Leader for the Minneapolis Institute of Art". The New York Times. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ Karen K. Ho (February 26, 2024). "Firing of Minneapolis Institute of Art of Curator Prompts Accusations of Toxic Work Environment". ART News.

- ^ Alex V. Cipolle (February 22, 2024). "Allegations of toxic work environment shake Minneapolis Institute of Art". MPR News.

- ^ Alicia Eler (February 23, 2024). "Firing at Mia sparks union accusations of toxic work environment". Star Tribune.

- ^ "William M. Griswold Appointed New Director of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts". Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ a b "New and Improved: The Minneapolis Institute of Arts Reopens". Antiques and the Arts Online. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ^ Among these is a 1784 piece believed to be the largest historic jade sculpture outside of China. "Jade Mountain Illustrating the Gathering of Poets at the Lan T'ing Pavilion". Art de l'Asie. www.framemuseums.org. Archived from the original on October 7, 2007. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ^ "Purcell–Cutts House". Collections.artsmia.org. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Unified Vision: The Architecture and Design of the Prairie School > The Purcell-Cutts Tour". Archive.artsmia.org. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "The Minnesota Artists Exhibition Program (MAEP)". artsmia.org. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Museum Library". Minneapolis Institute of Art. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

Located on the first floor of the Michael Graves-designed Target wing, the Art Research and Reference Library Reading Room is free and open to the public.

- ^ a b c Mault, Coco (October 24, 2011). "A Look at MIA's Outdoor Art". Minnesota.cbslocal.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Gehrz, Jim; Abbe, Mary (December 29, 2012). "Ella Pillsbury Crosby: Museum Lioness". Startribune.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Paret, Peter; Helga Thieme (April 30, 2012). Myth and Modernity: Barlach's Drawings on the Nibelungen. Berghahn Books. pp. 45–47. ISBN 978-0-85745-346-4.

- ^ "Erinnerungstag 19. Juni 1954: Geistkämpfer von Ernst Barlach vor der Nikolaikirche enthüllt". kiel.de (in German). Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ "The Fighter of the Spirit, Ernst Barlach". Collections.artsmia.org. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ "Gethsemanekirche: Prenzlauer Berg". Berlin1.de (in German). Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ "Chinese Rock Garden, China". Collections.artsmia.org. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "You searched for target park — Minneapolis Institute of Art". New.artsmia.org. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Labyrinth, John Willenbecher". Collections.artsmia.org. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Eros Bendato". inyourpocket.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Uren, Adam (April 28, 2015). "The Big, Bronze Head Worth $1M: Meet Minneapolis Museum's Newest Attraction". Bringmethenews.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Gateway Foundation". Gateway-foundation.org. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "This fund can only be used for the purchase of works of art." Arts, Minneapolis Institute of (1922). Handbook of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. p. viii. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ Dobrzynski, Judith H. (March 14, 2012). "A Fund for Buying Art Burnishes Collections and Reputations". New York Times. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Abbe, Mary (March 5, 2009). "MIA Cuts Staff, Programming". Startribune.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Abbe, Mary (April 20, 2011). "Minneapolis Institute of Arts Cuts Jobs to Salvage Budget". Startribune.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Abbe, Mary (August 18, 2016). "Minneapolis Institute of Art Gets $6 Million for "Gale Asian Art Initiative"". Startribune.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Markle, Peter (director) (1982). The Personals. YouTube (motion picture). 91 minutes in.

- ^ Abbe, Mary; Tribune, Star. "MIA sends Nazi 'loot' home to Paris". Star Tribune. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

That painting was bequeathed to the museum in 1961 by Minneapolis businessman Putnam Dana McMillan, a General Mills vice president who bought it from the Buchholz Gallery in New York in 1951.

- ^ "Museum returns painting found to be Nazi loot". NBC News. October 31, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ "Museum returns painting found to be Nazi loot". Associated Press. April 24, 2024. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

External links

[edit]- 1883 establishments in Minnesota

- Art museums and galleries established in 1883

- Art museums and galleries in Minnesota

- Arts organizations based in Minneapolis

- Asian art museums in the United States

- Beaux-Arts architecture in Minnesota

- Culture of Minneapolis

- FRAME Museums

- McKim, Mead & White buildings

- Michael Graves buildings

- Museums in Minneapolis

- African art museums in the United States