Earl Monroe

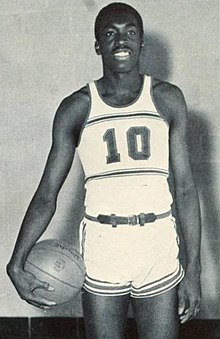

Monroe with Winston-Salem State in 1967 | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | November 21, 1944 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Listed height | 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m) |

| Listed weight | 185 lb (84 kg) |

| Career information | |

| High school | John Bartram (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) |

| College | Winston-Salem State (1963–1967) |

| NBA draft | 1967: 1st round, 2nd overall pick |

| Selected by the Baltimore Bullets | |

| Playing career | 1967–1980 |

| Position | Shooting guard / point guard |

| Number | 33, 10, 15 |

| Career history | |

| 1967–1971 | Baltimore Bullets |

| 1971–1980 | New York Knicks |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Career statistics | |

| Points | 17,454 (18.8 ppg) |

| Rebounds | 2,796 (3.0 rpg) |

| Assists | 3,594 (3.9 apg) |

| Stats at NBA.com | |

| Stats at Basketball Reference | |

| Basketball Hall of Fame as player | |

| College Basketball Hall of Fame Inducted in 2006 | |

Vernon Earl Monroe (born November 21, 1944) is an American former professional basketball player. He played for two teams, the Baltimore Bullets and the New York Knicks, during his career in the National Basketball Association (NBA). Both teams have retired Monroe's number. Due to his on-court success and flashy style of play, Monroe was given the nicknames "Black Jesus" and "Earl the Pearl". Monroe was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1990 and the International Sports Hall of Fame in 2013.[1] In 1996, Monroe was named as one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History, and in 2021, Monroe was named as one of the 75 greatest players in NBA history.[2][3]

Early years

[edit]Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Monroe was a playground legend from an early age. His high school teammates at John Bartram High School called him "Thomas Edison" because of the many moves he invented.

Growing up in his South Philadelphia neighborhood, Monroe was initially interested in soccer and baseball more than basketball. By age 14, Monroe was 6'3" and his interest in basketball grew, playing center during most of his youth. Some of his "shake-and-bake" style moves originated while playing on the asphalt playgrounds. "I had to develop flukey-duke shots, what we call la-la, hesitating in the air as long as possible before shooting," Monroe said.[4] As he was developing as a teenage player, other players would razz him. His mother gave Earl a blue notebook and told him to write down the names of those players. "As you get better than them," Monroe said his mother instructed, "I want you to scratch those names out."[5]

After graduating from John Bartram High School, Monroe attended a college preparatory school affiliated with Temple University. He worked as a shipping clerk in a factory, while frequently playing basketball at Leon Whitley's recreation center in Philadelphia.[6] Whitley had played at Winston-Salem Teacher College on their 1953 championship team and encouraged Monroe to attend Winston-Salem to play for coach Clarence "Big House" Gaines.[7]

College career

[edit]Monroe rose to prominence at a national level at then-Division II Winston-Salem State University, located in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Under Hall of Fame Coach Gaines, Monroe averaged 7.1 points his freshman year and Monroe tells a story of when he wanted to return to Philadelphia as a freshman. Coach Gaines called Monroe's mother and after a stern talk, Monroe stayed in college.[8]

Monroe then averaged 23.2 points as a sophomore, 29.8 points as a junior and 41.5 points his senior year (1,329 points in that 1966–1967 season). During that 1966–1967 season, Jerry McLeese, a sportswriter for the Winston-Salem Journal, called Monroe's points "Earl's pearls."[9] Soon after, fans began to chant "Earl, the Super Pearl," and the nickname was born.[10][7]

In 1967, Monroe earned NCAA College Division Player of the Year honors, leading the Rams to the 1967 NCAA College Division Championship with a 77–74 victory over SW Missouri State in the Final.[10]

Overall, in his four years at Winston-Salem State University, Monroe averaged 26.7 points, with 2,395 total points in 110 games.[10] He remains the leading scorer in Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association basketball history.[11]

After he finished his collegiate career, Monroe graduated from Winston-Salem and passed the national teaching exam. Monroe was not selected to the 1967 USA Basketball Team to represent the country at the 1967 Pan-American Games after trying out. The 40-person committee failed to select both Monroe and fellow future Hall of Fame player Elvin Hayes.[12][7][13][14] Monroe has said that USA coaches said his style of play was "too street, too playground, too black." adding, "It has always left a very, very bad taste in my mouth."[5]

NBA career

[edit]Baltimore Bullets (1967–1971)

[edit]In 1967, the two-time All-American was drafted number two overall by the Baltimore Bullets (now the Washington Wizards) in the first round of the 1967 NBA draft, behind Jimmy Walker, who was selected by the Detroit Pistons. Monroe then won the NBA Rookie of the Year Award in a season in which he averaged 24.3 points per game. He scored 56 points in a game against the Los Angeles Lakers, the third-highest rookie total in NBA history. It was also a franchise record, later broken by Gilbert Arenas on December 17, 2006.

Monroe and his teammate, future Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame inductee Wes Unseld, quickly became a formidable combination in Baltimore, and Monroe became a cult hero for his ability to run the fast break and for his circus-like shots. He said, "The thing is, I don't know what I'm going to do with the ball, and if I don't know, I'm quite sure the guy guarding me doesn't know either."[15] On February 6, 1970, he set an NBA record with 13 points in one overtime in a double-overtime victory over the Detroit Pistons (another mark since surpassed by Arenas).

In 1968–1969, Monroe averaged 25.8 points, 4.5 assists and 3.9 rebounds, as the Bullets finished 57–25 under coach Gene Shue, capturing the Eastern Division title. However, the Bullets were swept by the New York Knicks 4–0 in the playoffs after receiving a bye.[16]

The Bullets finished 50–32 in 1969–1970, as Monroe averaged 23.4 points, 4.9 assists and 3.1 rebounds, but did not make the NBA All-Star team. Oscar Robertson, Walt "Clyde" Frazier, Tom Van Arsdale, Hal Greer, and Flynn Robinson were the guards selected. The Bullets were again beaten by the Knicks 4–3 in the playoffs.[17]

In 1970–1971, the Bullets finished 42–40 under Coach Shue and captured the Central Division title. Monroe averaged 21.4 points, 4.4 assists and 2.6 rebounds. In the Eastern Conference playoffs, the Bullets defeated the Philadelphia 76ers 4–3, and then defeated the Knicks 4–3 in the Eastern Conference Finals to reach the 1971 NBA Finals.[18] Monroe averaged 23.0 points, 4.0 assists and 3.4 rebounds in the Philadelphia series.[19] He then averaged 24.4 points, 4.3 assists and 3.4 rebounds against the Knicks, including 26 points, 6 assists and 5 rebounds in the 93–91 Bullets' Game 7 victory.[20][21]

In the 1971 NBA Finals, the Bullets were matched against the Milwaukee Bucks with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Oscar Robertson and Bobby Dandridge. The Bucks swept the Bullets 4–0. Monroe averaged 16.3 points, 4.0 assists and 4.0 rebounds in the series.[22]

"Put a basketball in his hands and he does wondrous things with it," Bullets Coach Gene Shue said of Monroe. "He has the greatest combination of basketball ability and showmanship."[23]

In 328 games with the Bullets, Monroe averaged 23.7 points, 4.6 assists and 3.7 rebounds.[10]

New York Knicks (1971–1980)

[edit]After the 1970–1971 season, Monroe's agent Larry Fleisher informed the Bullets of Monroe's wishes to be traded to the Lakers, Chicago Bulls or his hometown Philadelphia 76ers. After four games into the 1971–1972 season, he traveled to Indianapolis to discuss a transfer to the American Basketball Association's Indiana Pacers.[24] He had begun the campaign without having signed a contract due to a salary dispute with Bullets management. When his trade request turned into an ultimatum, he was suspended by the team on October 22. He eventually signed a contract immediately after being sent from the Bullets to the New York Knicks for Mike Riordan, Dave Stallworth and an undisclosed amount of cash twenty days later on November 11, 1971.[25]

Upon his arrival with the Knicks, Monroe formed what was known as the "Rolls-Royce backcourt" with the equally flamboyant Walt Frazier. While there were initial questions as to whether Monroe and Frazier could coexist as teammates, the duo eventually meshed to become one of the most effective guard combinations of all time.

In 1971–1972, Monroe averaged 21.7 points in his three games with the Bullets before the trade and he struggled to adjust after the trade, averaging 11.4 points, 2.2 assists and 1.5 rebounds in 60 games with the Knicks.[10] However, the Knicks defeated the Bullets 4–2 and the Boston Celtics 4–1 to reach the 1972 NBA Finals. Monroe averaged 15.8 points and 3.3 assists in the Bullets' series against his former teammates.[26] In the Celtics series he averaged 13.6 points and 3.8 assists.[27]

In the 1972 NBA Finals, the Knicks were defeated by the Los Angeles Lakers with Jerry West and Wilt Chamberlain 4–1, losing four straight after winning Game 1. Monroe averaged 6.8 points and 2.6 assists in the series.[28]

In 1972–1973, Frazier and Monroe led the Knicks, under future Hall of Fame Coach Red Holtzman to the 1973 NBA Championship, along with future Hall of Fame teammates Bill Bradley, Jerry Lucas and Willis Reed, Dave DeBusschere and Phil Jackson.[29]

After a 57–25 regular season, in which Monroe averaged 15.5 points, 3.8 assists and 2.6 rebounds, his role on the team was defined. The Knicks then defeated the Bullets 4–1 and the Celtics 4–3 to reach the 1973 NBA Finals.[29][30] The Knicks had a rematch against the Los Angeles Lakers in the finals. The Knicks won the championship, four games to one, with Monroe averaging 16.0 points and 4.2 assists. Bradley averaged 18.6, Frazier 16.6, Reed 16.4 and DeBusschere 15.6 points to illustrate the Knicks' team play.[31]

In 1973–1974, the Knicks, after defeating the Bullets, were defeated by the eventual NBA Champion Celtics in the Eastern Conference Finals. Monroe averaged 14.0 points and 2.7 assists with 3.0 rebounds in the regular season.[32]

In the next four seasons, Monroe averaged 20.9 points, 20.7 points, 19.9 points and 17.8 points, before injures limited him in games and minutes during his final two seasons.

The Monroe-Frazier pairing is one of few backcourts ever to feature two Hall of Famers and NBA 50th Anniversary Team members. A four-time NBA All-Star, Monroe retired after the 1980 season due to serious knee injuries, which had plagued him throughout his career. In nine seasons and 592 games with the Knicks, Monroe averaged 16.2 points, 3.5 assists and 2.6 rebounds.[10]

Overall, Monroe played in 926 regular season NBA games, scoring 17,454 total points with 3,594 assists on 46% shooting. He averaged 18.8 points, 3.9 assists and 3.0 rebounds in his career. He scored over 1,000 points in nine of his thirteen professional seasons (1968–71, 1973, 1975–78) including a career-high 2,065 (25.8 points per game) in the 1968–69 season.[10]

In 2021, to commemorate the NBA's 75th Anniversary The Athletic ranked their top 75 players of all time, and named Monroe as the 58th greatest player in NBA history.[33]

Of his unique, flowing, fluid, silky-smooth on-court style of play, Monroe has said: "You know, I watch the games and even now I never see anyone who reminds me of me, the way I played."[34] "The ultimate playground player," is how Bill Bradley once described Monroe.[4]

"If for any reason someone were to remember me," Monroe said, "I hope they will remember me as a person who could play the game and excite the fans and excite himself."[23]

Personal life

[edit]

- Monroe has one son, Rodney (not the former NC State and NBA basketball player), and one daughter, Maya. Maya has coached in high school and college.[35]

- Earl Monroe and NC State basketball player Rodney did meet following an NC State game in 1990.[36]

- Monroe was named commissioner of the United States Basketball League in 1985.

- In 2012 Monroe launched a new candy company: NBA Candy Store [1]

- In recent years, he has been serving as a commentator for Madison Square Garden and as commissioner of the New Jersey Urban Development Corporation.

- Monroe has also been active in various community affairs and programs, including the President's Council on Physical Fitness and Health, the Crown Heights Youth Collective, the Literary Assistance Fund and the Harlem Junior Tennis Program. He has received many honors for these "off-the-court" community activities, including the Harlem Professionals Inspirational Award, Most Outstanding Model for American Youth, the YMCA Citizenship Award and Big Apple Sportsman of the Year Award.

- Monroe served as a spokesman for the American Heart Association, along with his former Knicks teammate Walt "Clyde" Frazier.

- In October 2005, Monroe opened a restaurant in New York City, named "Earl Monroe's Restaurant & Pearl Club". However, Monroe has since revoked the licensing rights to his name and the restaurant is now called The River Room.[37]

- Monroe, his brother and his sister all have been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.[38]

- Monroe is a spokesman for Merck's Journey for Control website, where he serves as a promoter of diabetes-friendly eating and "Diabetes Restaurant Month!"[39]

- Monroe owns and operates his own record label, Reverse Spin Records, in New York, doing pop, dance, hip-hop and R&B music, currently with pop/dance artist Ciara Corr.[40][41]

- In the Spike Lee film He Got Game, Jake Shuttlesworth (Denzel Washington) explains to his son, Jesus Shuttlesworth (Ray Allen), that his name was inspired by Monroe's nickname: "Jesus".

- Monroe is also a member of Groove Phi Groove

- From 1980 to 1981, Monroe had an endorsement deal with Jordache for a signature line of basketball sneakers that bore his nickname "Pearl" near the heel.[42]

Honors

[edit]- In 1977, Monroe was inducted into the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association Hall of Fame.[43]

- Monroe's number 15 jersey was retired by the New York Knicks on March 1, 1986.

- In 1990, he was enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

- Monroe was named one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History in 1996.

- In 2006, Monroe was inducted into the College Basketball Hall of Fame.

- On December 1, 2007, the Washington Wizards retired Monroe's number 10 jersey.[44]

- In 2005, an American Basketball Association team, the Baltimore Pearls, was named in honor of Earl Monroe.

- Monroe's number 10 jersey was retired by Winston-Salem in 2017.[8]

- In 2021, Monroe was elected to the NBA 75th Anniversary Team.

NBA career statistics

[edit]| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

| † | Won an NBA championship |

Regular season

[edit]| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1967–68 | Baltimore | 82 | — | 36.7 | .453 | — | .781 | 5.7 | 4.3 | — | — | 24.3 |

| 1968–69 | Baltimore | 80 | — | 38.4 | .440 | — | .768 | 3.5 | 4.9 | — | — | 25.8 |

| 1969–70 | Baltimore | 82 | — | 37.2 | .446 | — | .830 | 3.1 | 4.9 | — | — | 23.4 |

| 1970–71 | Baltimore | 81 | — | 35.1 | .442 | — | .802 | 2.6 | 4.4 | — | — | 21.4 |

| 1971–72 | Baltimore | 3 | — | 34.3 | .406 | — | .722 | 2.7 | 3.3 | — | — | 21.7 |

| 1971–72 | New York | 60 | — | 20.6 | .436 | — | .786 | 1.5 | 2.2 | — | — | 11.4 |

| 1972–73† | New York | 75 | — | 31.6 | .488 | — | .822 | 3.3 | 3.8 | — | — | 15.5 |

| 1973–74 | New York | 41 | — | 29.1 | .468 | — | .823 | 3.0 | 2.7 | .8 | .5 | 14.0 |

| 1974–75 | New York | 78 | — | 36.1 | .457 | — | .827 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 1.4 | .4 | 20.9 |

| 1975–76 | New York | 76 | — | 38.0 | .478 | — | .787 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 1.5 | .3 | 20.7 |

| 1976–77 | New York | 77 | — | 34.5 | .517 | — | .839 | 2.9 | 4.8 | 1.2 | .3 | 19.9 |

| 1977–78 | New York | 76 | — | 31.2 | .495 | — | .832 | 2.4 | 4.8 | .8 | .3 | 17.8 |

| 1978–79 | New York | 64 | — | 21.8 | .471 | — | .838 | 1.2 | 3.0 | .8 | .1 | 12.3 |

| 1979–80 | New York | 51 | — | 12.4 | .457 | — | .875 | .7 | 1.3 | .4 | .1 | 7.4 |

| Career | 926 | — | 32.0 | .464 | — | .807 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 1.0 | .3 | 18.8 | |

| All-Star | 4 | 3 | 21.3 | .359 | — | .706 | 3.0 | 2.8 | .3 | .0 | 10.0 | |

Playoffs

[edit]| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | Baltimore | 4 | — | 42.8 | .386 | — | .806 | 5.3 | 4.0 | — | — | 28.3 |

| 1970 | Baltimore | 7 | — | 42.7 | .481 | — | .800 | 3.3 | 4.0 | — | — | 28.0 |

| 1971 | Baltimore | 18 | — | 37.3 | .407 | .793 | 3.6 | 4.1 | — | — | 22.1 | |

| 1972 | New York | 16 | — | 26.8 | .411 | — | .789 | 2.8 | 2.9 | — | — | 12.3 |

| 1973† | New York | 16 | — | 31.5 | .526 | — | .750 | 3.2 | 3.2 | — | — | 16.1 |

| 1974 | New York | 12 | — | 33.9 | .491 | — | .855 | 4.0 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 17.4 |

| 1975 | New York | 3 | — | 29.7 | .267 | — | .818 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 14.0 |

| 1978 | New York | 6 | — | 24.2 | .387 | — | .611 | 0.8 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 9.8 |

| Career | 82 | — | 33.1 | .439 | — | .791 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 17.9 | |

References

[edit]- ^ Dr. Robert Goldman (March 12, 2013). "2013 International Sports Hall of Fame Inductees". www.sportshof.org. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ NBA at 50: Top 50 Players at NBA.com. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ^ NBA’s 75 Anniversary Team Players at NBA.com. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ^ a b "NBA.com: Earl Monroe Bio". www.nba.com.

- ^ a b "The 5 Best Stories From Earl Monroe at Drew University". Drew University.

- ^ Cady, Steve. "Earl Monroe: A Spectacular Shooter and a Master Showman", The New York Times, November 14, 1971. Accessed February 22, 2021. "At John Bartram High School, Monroe played center. After graduation, he spent one semester at Temple Prep before dropping out to take a $60‐a‐week job as a shipping clerk."

- ^ a b c "Vernon Earl/Earl the Pearl Monroe (1944- ) • BlackPast". July 16, 2012.

- ^ a b Bell, Daryl (February 7, 2017). "Winston-Salem State retires Earl 'The Pearl' Monroe's number". The Philadelphia Tribune.

- ^ "Ram Ramblings: Jerry McLeese, who gave Earl 'The Pearl' Monroe his nickname, has died". April 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Earl Monroe Stats". Basketball-Reference.com.

- ^ "Top 50 CIAA Basketball scorers of all-time". March 15, 2020.

- ^ "Becoming 'Earl the Pearl': How Earl Monroe earned his famous nickname". Sporting News. April 24, 2013.

- ^ "Reusse: NAIA stars stole the show at 1967 Pan Am Games auditions - StarTribune.com". www.startribune.com. Archived from the original on August 20, 2017.

- ^ "Fifth Pan American Games – 1967". www.usab.com. Archived from the original on May 6, 2015.

- ^ "Monroe's biography at". Nba.com. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "1968-69 Baltimore Bullets Roster and Stats". Basketball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1969-70 Baltimore Bullets Roster and Stats". Basketball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1970-71 Baltimore Bullets Roster and Stats". Basketball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1971 NBA Eastern Conference Semifinals - Philadelphia 76ers vs. Baltimore Bullets". Basketball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1971 NBA Eastern Conference Finals - Baltimore Bullets vs. New York Knicks". Basketball-Reference.com.

- ^ "Baltimore Bullets at New York Knicks Box Score, April 19, 1971". Basketball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1971 NBA Finals - Baltimore Bullets vs. Milwaukee Bucks". Basketball-Reference.com.

- ^ a b "Legends profile: Earl Monroe". NBA.com.

- ^ Sheridan, Chris (June 13, 2011). "For Monroe, ring not always the thing". ESPNNewYork.com. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Rogers, Thomas. "Stallworth and Riordan Sent to Baltimore," The New York Times, Friday, November 12, 1971. Retrieved May 19, 2020

- ^ "1972 NBA Eastern Conference Semifinals - New York Knicks vs. Baltimore Bullets". Basketball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1972 NBA Eastern Conference Finals - New York Knicks vs. Boston Celtics". Basketball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1972 NBA Finals - New York Knicks vs. Los Angeles Lakers". Basketball-Reference.com.

- ^ a b "1972-73 New York Knicks Roster and Stats". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ "Earl Monroe - American basketball player". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ "1973 NBA Finals - New York Knicks vs. Los Angeles Lakers". Basketball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1973-74 New York Knicks Roster and Stats". Basketball-Reference.com.

- ^ "NBA 75: At No. 58, Earl Monroe dazzled with his flashy dribbling and spectacular shooting".

- ^ Jacobson, Mark (October 31, 2005). "Knicks Legend Earl the Pearl Monroe Ups the Ante on Jock Food". Nymag.com. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "Maya Monroe, Daughter of New York Knick Great Earl Monroe, Named York College Assistant Women's Basketball Coach – CUNY Newswire". Archived from the original on February 18, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ "Wolfpack's Monroe Still Pearl in His Mother's Eyes". Los Angeles Times. January 14, 1990. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ^ "www.theriverroomofharlem.com is Expired or Suspended". www.theriverroomofharlem.com. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ "NBA Legends Frazier and Monroe Team up Once More to Educate". Diabeteshealth.com. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "Home Court of Diabetes Restaurant Month". Journeyforcontrol.com. Archived from the original on November 26, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Klingaman, Mike (October 6, 2009). "Catching Up With...former Bullet Earl Monroe". The Baltimore Sun. The Toy Department. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "About". Reverse Spin Records. Archived from the original on August 26, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "Jordache Earl "The Pearl" Monroe Sneaker 1980-1981 « DeFY. New York-Sneakers,Music,Fashion,Life". Defynewyork.com. September 29, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "Earl "The Pearl" Monroe (1977) - CIAA Hall of Fame Members".

- ^ "Wizards retiring Earl Monroe's No. 10". CBC. November 21, 2007.

Bibliography

[edit]Monroe, Earl; Troupe, Quincy (2013). Earl The Pearl: My Story.

External links

[edit]- 1944 births

- Living people

- American men's basketball players

- Baltimore Bullets (1963–1973) draft picks

- Baltimore Bullets (1963–1973) players

- Basketball players from Philadelphia

- John Bartram High School alumni

- Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame inductees

- NBA All-Stars

- NBA broadcasters

- NBA players with retired numbers

- National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame inductees

- New York Knicks players

- Point guards

- Shooting guards

- Winston-Salem State Rams men's basketball players

- 21st-century African-American sportspeople

- 20th-century African-American sportspeople