Distilled water

Distilled water is water that has been boiled into vapor and condensed back into liquid in a separate container. Impurities in the original water that do not boil below or near the boiling point of water remain in the original container. Thus, distilled water is a type of purified water.

History

[edit]Drinking water has been distilled from seawater since at least about AD 200, when the process was clearly described by Alexander of Aphrodisias.[1] Its history predates this, as a passage in Aristotle's Meteorologica refers to the distillation of water.[2] Captain Israel Williams of the Friendship (1797) improvised a way to distill water, which he described in his journal.[3]

Applications

[edit]In chemical and biological laboratories, as well as in industry, in some appliances, deionized water or reverse osmosis water can be used instead of distilled water as a cheaper alternative. If exceptionally high-purity water is required, double distilled water is used.

In general, non-purified water could cause or interfere with chemical reactions as well as leave mineral deposits after boiling away. One method of removing impurities from water and other fluids is distillation.

For example, ions commonly found in tap water would drastically reduce lifespans of lead–acid batteries used in cars and trucks. These ions are not acceptable in automotive cooling systems because they corrode internal engine components and deplete typical antifreeze anti-corrosion additives.[4]

Any non-volatile or mineral components in water are left behind when the water evaporates or boils away. Water escaping as steam, for example from a boiler of heating system or steam engine, leaves behind any dissolved materials leading to mineral deposits known as boiler scale.

Low-volume humidifiers such as cigar humidors can use distilled water to avoid mineral deposits.[5]

Certain biological applications require controlled impurities, especially in experiments. For example, distilling water to be added to an aquarium would remove known and unknown non-volatile contaminants. Living things require specific minerals; adding distilled water to an ecosystem, such as an aquarium, would reduce the concentration of these minerals. Fish and other living things that have evolved to survive in lakes and oceans should be expected to thrive at mineral ranges found in their original habitat.[6]

Controlled impurities as well as equipment reliability are critically important in medical applications where, for example, distilled water is used in continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines to humidify air for breathing. Distilled water will not leave contaminants behind when the humidifier in the CPAP machine evaporates the water.[7][8]

It is also possible for brewers to blend distilled water with hard water to mimic the soft waters of Pilsen.[9]

Another application was to increase the density of the air to assist early airplane jet engines during takeoff in 'hot and high' atmospheric conditions, as was used on the early Boeing 707.[10]

Use in steam irons

[edit]Distilled water can be used in steam irons for pressing clothes to minimize the build-up of limescale in hard water areas shortening the lifespan of steam irons. Some steam irons have built in filters to remove minerals from the water meaning standard tap water can be used.

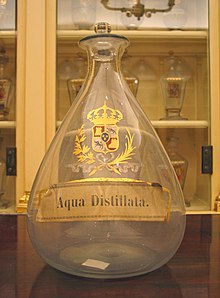

Equipment to distill water

[edit]

Until World War II, distilling seawater to produce fresh water was time-consuming and expensive in fuel. The saying was: "It takes one gallon of fuel to make one gallon of fresh water."[citation needed] Shortly before the war, Dr. R. V. Kleinschmidt developed a compression still, which became known as the Kleinschmidt still, for extracting fresh water from seawater or contaminated water. By compressing the steam produced by boiling water, 175 US gal (660 L; 146 imp gal) of fresh water could be extracted from seawater for every gallon (3.8 L; 0.83 imp gal) of fuel used. During World War II this equipment became standard on Allied ships and on trailer mounts for armies. This method was in widespread use in ships and portable water distilling units[11] during the latter half of the century. Modern vessels now use flash-type evaporators to boil seawater, heating the water to between 70 and 80 °C (158 and 176 °F) and evaporating the water in a vacuum; this is then collected as condensation before being stored.

Solar stills can be relatively simple to design and build, with very cheap materials.[12]

Distilling water with commercial equipment will almost completely remove all dissolved minerals such as calcium, magnesium, sodium, fluoride, potassium, iron, and zinc leaving a TDS of <1PPM, and reduce its electrical conductivity to <2 μS/cm. Typical tap water has electrical conductivity in the range of 200–800 μS/cm. The pH of distilled water is always slightly lower than 7 (neutral) due to the fact that distilled water will absorb small amounts of carbon dioxide gas from the atmosphere which forms traces of carbonic acid and lowers the pH of distilled water to around 5.8 pH (very weakly acidic).[13]

Drinking distilled water

[edit]Bottled distilled water can usually be found in supermarkets or pharmacies, and home water distillers are available as well. Water purification, such as distillation, is especially important in regions where water resources or tap water is not suitable for ingesting without boiling or chemical treatment.

Municipal water supplies almost always contain trace components at levels which are regulated to be safe for consumption.[14] Some other components such as trace levels of aluminium may result from the treatment process. Fluoride and other ions are not removed through conventional water filter treatments. However, distillation eliminates most impurities.[15]

Distilled water is also used for drinking water in arid seaside areas lacking sufficient freshwater, via desalination of seawater.[16]

Health effects

[edit]Distillation removes all minerals from water. This results in demineralised water, which has not been proven to be healthier than drinking water. The World Health Organization investigated the health effects of demineralised water in 1982, and its experiments in humans found that demineralised water increased diuresis and the elimination of electrolytes, with decreased serum potassium concentration.[citation needed] Magnesium, calcium, and other nutrients in water can help to protect against nutritional deficiency. Recommendations for magnesium have been put at a minimum of 10 mg/L with 20–30 mg/L optimum; for calcium a 20 mg/L minimum and a 40–80 mg/L optimum, and a total water hardness (adding magnesium and calcium) of 2–4 mmol/L. At water hardness above 5 mmol/L, higher incidence of gallstones, kidney stones, urinary stones, arthrosis, and arthropathies have been observed.[citation needed] For fluoride the concentration recommended for dental health is 0.5–1.0 mg/L, with a maximum guideline value of 1.5 mg/L to avoid dental fluorosis.[17]

Water filtration and distillation devices are becoming increasingly common in households. Municipal water supplies often have minerals added or have trace impurities at levels which are regulated to be safe for consumption. Much of these additional impurities, such as volatile organic compounds, fluoride, and an estimated >75,000 other chemical compounds[18] are not removed through conventional filtration; however, distillation and reverse osmosis eliminate nearly all of these impurities.

The drinking of distilled water as a replacement for drinking water has been both advocated and discouraged for health reasons. Distilled water lacks minerals and ions, such as calcium, that play key roles in biological functions, such as in nervous system homeostasis, and are normally found in potable water. The lack of naturally occurring minerals in distilled water has raised some concerns. The Journal of General Internal Medicine published a study on the mineral contents of different waters available in the US. The study found that "drinking water sources available to North Americans may contain high levels of calcium, magnesium, and sodium and may provide clinically important portions of the recommended dietary intake of these minerals". It encouraged people to "check the mineral content of their drinking water, whether tap or bottled, and choose water most appropriate for their needs". Since distilled water is devoid of minerals, mineral intake through diet is needed to maintain good health.[19]

The consumption of "hard" water (water with minerals) is associated with beneficial cardiovascular effects. As noted in the American Journal of Epidemiology, consumption of hard drinking water is negatively correlated with atherosclerotic heart disease.[20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Taylor, F. Sherwood (1945). "The Evolution of the Still". Annals of Science. 5 (3): 186. doi:10.1080/00033794500201451. ISSN 0003-3790.

- ^ Aristotle. "Meteorology – Book II". The University of Adelaide. II.3, 358b16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-04-26. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ Trow, Charles Edward (1905). "Chapter XVI". The old shipmasters of Salem. New York and London: G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 178ff. OCLC 4669778.

Short of Fresh Water Causes Alarm — Captain Williams's Invention to Make Salt Water Fresh — His 'Still' Described by him

- ^ Pollution Prevention Fact Sheet Antifreeze Recycling & Disposal. Utah Department of Environmental Quality, US

- ^ "Distilled water | Empire City Auto Parts". 2020-06-19. Retrieved 2021-09-22.

- ^ "Basic Aquarium System Set-Up Trout-in-the-Classroom" (PDF). Department of Fish and Game. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- ^ "Distilled Water And CPAP Usage". cpap.com. Archived from the original on 2014-07-05.

- ^ "CPAP Humidifier Frequently Asked Questions - CPAP.com". cpap.com. Archived from the original on 2014-07-05.

- ^ "How to Brew – By John Palmer – Reading a Water Report". howtobrew.com. Archived from the original on 2009-10-05.

- ^ Down the Susquehanna to the Chesapeake by John H. Brubaker, Jack Brubaker – page 163

- ^ Bonnier Corporation (February 1946). Popular Science.

- ^ "Solar Water Distiller". thefarm.org. Archived from the original on 2009-08-19. Retrieved 2009-09-03.

- ^ Kulthanan, Kanokvalai; Nuchkull, Piyavadee; Varothai, Supenya (2013). "The pH of water from various sources: an overview for recommendation for patients with atopic dermatitis". Asia Pacific Allergy. 3 (3): 155–160. doi:10.5415/apallergy.2013.3.3.155. PMC 3736366. PMID 23956962. Distilled Water pH, 2022, retrieved 22 February 2023

- ^ "Drinking Water Contaminants". water.epa.gov. 2011. Archived from the original on February 2, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ Anjaneyulu, L.; Kumar, E. Arun; Sankannavar, Ravi; Rao, K. Kesava (13 June 2012). "Defluoridation of Drinking Water and Rainwater Harvesting Using a Solar Still". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 51 (23): 8040–8048. doi:10.1021/ie201692q.

- ^ Kozisek, F. (2005). "Health risks from drinking demineralised water (application/pdf Object)" (PDF). who.int. Retrieved October 25, 2011. (Chapter 12 of the World Health Organization report Nutrients in drinking-water)

- ^ Kozisek F. (1980). "Health risks from drinking demineralised water" (PDF). Nutrients in Drinking Water. World Health Organization. pp. 148–159. ISBN 92-4-159398-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-02-18.

- ^ "Walton International – Home". Watersystems.walton.com. 2010-11-05. Archived from the original on 2014-09-04. Retrieved 2011-12-11.

- ^ Azoulay A.; Garzon P.; Eisenberg M. J. (2001). "Comparison of the mineral content of tap water and bottled waters". J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16 (3): 168–175. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.04189.x. PMC 1495189. PMID 11318912.

- ^ Voors, A. W. (April 1, 1971). "Mineral in the municipal water and atherosclerotic heart death". American Journal of Epidemiology. Vol. 93, no. 4. pp. 259–266. PMID 5550342. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007.