Grant County, Oregon

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2007) |

Grant County | |

|---|---|

Grant County Courthouse in Canyon City | |

Location within the U.S. state of Oregon | |

Oregon's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 44°26′18″N 118°53′30″W / 44.43841°N 118.89173°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | October 14, 1864 |

| Named for | Ulysses S. Grant |

| Seat | Canyon City |

| Largest city | John Day |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4,529 sq mi (11,730 km2) |

| • Land | 4,529 sq mi (11,730 km2) |

| • Water | 0.7 sq mi (2 km2) 0.02% |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 7,233 |

| • Estimate (2023) | 7,215 |

| • Density | 1.6/sq mi (0.6/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| Congressional district | 2nd |

| Website | www |

Grant County is one of the 36 counties in the U.S. state of Oregon. As of the 2020 census, the population was 7,233,[1] making it Oregon's fourth-least populous county. The county seat is Canyon City.[2] It is named for President Ulysses S. Grant,[3] who served as an army officer in the Oregon Territory, and at the time of the county's creation was a Union general in the American Civil War.

Grant County is included in the eight-county definition of Eastern Oregon.

History

[edit]Grant County was established on October 14, 1864, from parts of old Wasco and old Umatilla counties. Prior to its creation, cases brought to court were tried in The Dalles, county seat of the vast Wasco County. The great distance to The Dalles made law enforcement a difficult problem, and imposed a heavy burden on citizens who had a need to transact business at the courthouse. In 1889, more than half of the southern part of the original Grant County was taken to form Harney County. Also in 1899, a small part of northwestern Grant County was taken (along with parts of Crook and Gilliam counties) to form Wheeler County.[4]

After gold was discovered in 1862 on Whiskey Flat, it has been estimated that within ten days 1,000 miners were camped along Canyon Creek. This increased population created a need for county government. Grant County's government operates in accordance with the Oregon Constitution which was ratified by the People of Oregon in November 1857, and the revised Statutes of Oregon. It employs the old-western county government system: the County Court, with a County Judge and two Commissioners. While the County Court no longer exercises much judicial authority, it serves as the executive branch of county government.

The third man to serve as County Judge of Grant County was Cincinnatus Hiner "Joaquin" Miller (1837–1913), the noted poet, playwright, and western naturalist, called the "Poet of the Sierras" and the "Byron of the Rockies."

The county seat is Canyon City, which served as the chief community of the county for many years. In 1864, when the county was organized, Canyon City is said to have boasted the largest population of any community in Oregon. Mining and ranching, along with timber and then the service and public works that followed, brought people into the area and communities grew around the natural centers of industry and agriculture. Canyon City hosts an annual summer festival called "'62 Days" (referencing the local gold discovery in 1862) to celebrate its history and residents.

Since the 1930s, the city of John Day has served as the main economic center of the county, and boasts the largest population.

Geography

[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 4,529 square miles (11,730 km2), of which 4,529 square miles (11,730 km2) is land and 0.7 square miles (1.8 km2) (0.02%) is water.[5]

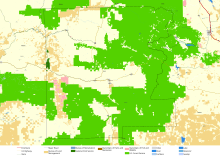

Approximately 63% of the land area of the county is controlled by the Federal Government, most of which is controlled by the U.S. Forest Service, and the Bureau of Land Management. Grant County contains most of the Malheur National Forest and sections of the Wallowa–Whitman, Umatilla and Ochoco National Forests, and has more than 150,000 acres (610 km2) of federally designated Wilderness Areas.

Grant County contains the headwaters of the John Day River, which has more miles of Wild and Scenic River designation than any other river in the United States.

The elevation of the county varies from 1,820 on the John Day River near Kimberly, to 9,038 feet (2,755 m) at the summit of Strawberry Mountain. The terrain of the county varies from grassland steppes and rangelands in relatively open or rolling hills and valleys, to steep, rugged, rocky high-alpine landscapes. Between these, the county contains heavily timbered land, many rolling hills, canyons and mountainous terrain. Portions of the county are technically high desert, dominated by sagebrush and sparse grasses.

Grant County includes the southern part of the Blue Mountains. One unique characteristic of the typical forestland of the area is the relatively low density of underbrush. Travelers and emigrants of the 19th century remarked that the absences of underbrush, and the wide spacing of the trees, made it possible to drive a wagon and team of horses virtually anywhere the grade would permit. The forested land of the county vary from sparse stands of Western Juniper in more arid, open, or rocky ground, to spruce-fir stands in the highest terrain. Other forested areas (mainly above 3,200 feet (980 m) in elevation) are marked by stands of Ponderosa Pine, Douglas-fir, hybrid Grand x White Fir, Western Larch and Lodgepole Pine. At high elevations there are stands of Engelmann Spruce, Subalpine Fir, and Whitebark Pine, as well as a few stands of Western White Pine. Cottonwoods grow along some rivers and streams, and there are small groves of birch and Quaking Aspen at higher elevations. There is also a rare and isolated stand of Alaska Yellow Cedar in the Aldrich Mountains. Other flora includes a wide variety of native grasses and wildflowers, huckleberries, wild strawberries, elderberries, several types of edible mushrooms and Oregon-grape, the state plant. Non-native Cheatgrass is also prevalent in many areas of the county.

Grant County is also home to what may be one of the largest living organism in the world, a giant fungus of the species Armillaria solidipes that lives within the Malheur National Forest. It was found to span 8.9 square kilometres (2,200 acres). Its total mass has been estimated to be between 8,500 and 10,500 tons, and its age at somewhere between 2,000 and 8,500 years.[6]

The physical terrain one encounters today is far different than in prehistoric times. Fossil records show that, in the Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras, much of the county was an ancient seabed. After emerging, the absence of the Cascade Mountains allowed the region to experience a relatively wet temperate climate. Ancient Tertiary rivers flowed through the area on courses that would be impossible today. During the Cenozoic Era, volcanic activity and extensive lava flows in the region dramatically changed the landscape. The John Day Fault (one of the only major faults in North America to run east–west) runs along the southern edge of the John Day Valley, caused an uplift, forming the Strawberry and Aldrich mountain ranges and the northern boundary of the Great Basin. Relatively recently in geological terms, during the last Ice age and shortly thereafter, large lakes were present in southeastern Oregon. Continual glaciers were still clinging to mountains in the area in the late 19th century, and one small glacier on Strawberry Mountain often remains year-round.

The geology of Grant County is rich, including one of the largest fossil concentrations in North America: The John Day Fossil Beds, which the U.S. Congress designated as a National Monument in 1974. Valuable metals, including gold, silver, platinum group elements, chrome, copper and cobalt, are found in the region. It was this mineral wealth, and the development of gold mines in particular, that spurred the permanent settlement of the area. Large zones of serpentine, a metamorphic rock, dating from the Triassic period, are found in numerous locations. Strawberry Mountain (an extinct volcano), the granite peaks and boulders of the Elkhorn Mountains, and numerous rim rocks, lava flows and basalt outcrops are evidence of the historic volcanic activity in the region. Hydrothermal resources are still present, with a number of hot and warm springs.

The remnants of ferns, semi-tropical and temperate deciduous forests, shellfish, saber-toothed cats, extinct horse and camel species, and giant sloth, among other extinct species found in the John Day Fossil Beds, are a reminder that the flora and fauna of the region has changed significantly over the millennia. While deer, elk, pronghorn, cougar, bear and upland game bird populations thrive today, some of these animals were remarkably scarce 200 years ago. Explorers and trappers traveling through the region in the early 19th century remarked on the scarcity of game animals and their ability (or inability, as the case were) to find food.

Native fish in the region include several trout species; warm water fish such as bass and perch are found in the lower John Day River; and migratory salmon and steelhead are found in the county seasonally. While salmon and steelhead returns to the John Day Basin experienced a sharp decline during the past 50 years, mainly due to the construction of large dams on the Columbia River, the major watercourses of John Day Basin remain free of physical obstructions, and the numbers of returning salmon and steelhead have improved in recent years, marking some of the best fish runs recorded in the past half-century.

Most of Grant County is drained by the four forks of the John Day River, all of which have their headwaters in the county. The John Day River system drains some 7,900 square miles (20,000 km2). It is the third longest free-flowing river in the "lower 48" and has more miles of federal "Wild and Scenic River" designation than any other river in the United States. The river system in Grant County includes the upper 100 miles (160 km) of the Main Stem, all of the 112 miles (180 km) of the North Fork, all 75 miles (121 km) of the Middle Fork, and all 60 miles (97 km) of the South Fork of the John Day River. From Grant County, the lower John Day River flows another 184 miles (296 km) to its confluence with the Columbia River. The southeastern corner of the county includes the headwaters of the Malheur and Little Malheur rivers, which find their way to the Snake River. The southern part of Grant County includes the northernmost reaches of the Great Basin, including the Silvies River watershed, which flows south into Harney Lake in the High Desert of Eastern Oregon. A small area in the southwestern corner of Grant County is in the Crooked River and Deschutes River watersheds.

Grant County is an arid to temperate region, with average annual precipitation ranging from 9 inches (230 mm) near Picture Gorge, to over 40 inches (1,000 mm) in the Strawberry Mountains. Annual precipitation in the valleys averages between 12 and 14 inches (360 mm), while the uplands or highlands of the county average between 16 and 24 inches (610 mm). Grant County averages between 40 and 60 days each year that see more than 0.10 inches (2.5 mm) of precipitation. A great deal of the county's precipitation comes in the form of winter snow in the mountains. This snow pack is vital to recharge aquifers, resulting in spring run-off, and in-stream flows of water throughout the year.

Average temperatures in the county range from the warmest community, Monument, with average daily highs/lows of 90°/50 °F in July and 42°/22 °F in January; to the coolest community, Seneca, with average daily highs/lows of 80°/38 °F in July and 33°/8 °F in January. Extreme temperatures in the county show 30-year highs/lows of: 103°/-37 °F at Austin; 112°/-23 °F at John Day; 108°/-25 °F at Long Creek; 112°/-26 °F at Monument; and 100°/-48 °F at Seneca.

Grant County has an estimated 200 days of clear sunny or mostly sunny days, or an estimated 300 days of clear sunny, mostly sunny, or partly sunny days each year. The county experiences an estimated 65 days of overcast skies, with about 165 days of partly to mostly cloudy days annually.

Adjacent counties

[edit]Grant County is bordered by a total of eight Oregon counties. This is the most of any county in the state.

- Morrow County - northwest

- Umatilla County - north

- Union County - northeast

- Baker County - east

- Malheur County - southeast/Mountain Time Border

- Harney County - south

- Crook County - southwest

- Wheeler County - west

National protected areas

[edit]- John Day Fossil Beds National Monument (part)

- Malheur National Forest (part)

- Ochoco National Forest (part)

- Umatilla National Forest (part)

- Wallowa–Whitman National Forest (part)

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 2,251 | — | |

| 1880 | 4,303 | 91.2% | |

| 1890 | 5,080 | 18.1% | |

| 1900 | 5,948 | 17.1% | |

| 1910 | 5,607 | −5.7% | |

| 1920 | 5,496 | −2.0% | |

| 1930 | 5,940 | 8.1% | |

| 1940 | 6,380 | 7.4% | |

| 1950 | 8,329 | 30.5% | |

| 1960 | 7,726 | −7.2% | |

| 1970 | 6,996 | −9.4% | |

| 1980 | 8,210 | 17.4% | |

| 1990 | 7,853 | −4.3% | |

| 2000 | 7,935 | 1.0% | |

| 2010 | 7,445 | −6.2% | |

| 2020 | 7,233 | −2.8% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 7,215 | [7] | −0.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[8] 1790–1960[9] 1900–1990[10] 1990–2000[11] 2010–2020[1] | |||

2010 census

[edit]As of the 2010 census, there were 7,445 people, 3,352 households, and 2,167 families residing in the county.[12] The population density was 1.6 inhabitants per square mile (0.62/km2). There were 4,344 housing units at an average density of 1.0 units per square mile (0.39 units/km2).[13] The racial makeup of the county was 95.0% white, 1.2% American Indian, 0.3% Asian, 0.2% black or African American, 0.1% Pacific islander, 0.9% from other races, and 2.3% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 2.8% of the population.[12] In terms of ancestry, 27.7% were German, 16.3% were English, 12.6% were Irish, 7.5% were American and 5.4% were Scottish.[14]

Of the 3,352 households, 22.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 54.1% were married couples living together, 7.5% had a female householder with no husband present, 35.4% were non-families, and 30.3% of all households were made up of individuals. The average household size was 2.19 and the average family size was 2.69. The median age was 50.0 years.[12]

The median income for a household in the county was $35,974 and the median income for a family was $43,521. Males had a median income of $40,603 versus $27,326 for females. The per capita income for the county was $22,041. About 11.4% of families and 14.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 19.3% of those under age 18 and 11.9% of those age 65 or over.[15]

2000 census

[edit]As of the 2000 census, there were 7,935 people, 3,246 households, and 2,233 families residing in the county. The population density was 2 people per square mile (0.77 people/km2). There were 4,004 housing units at an average density of 1 units per square mile (0.39/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 95.69% White, 0.10% Black or African American, 1.60% Native American, 0.19% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.68% from other races, and 1.70% from two or more races. 2.05% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. 17.5% were of English, 17.1% German, 14.3% American and 9.0% Irish ancestry.

There were 3,246 households, out of which 30.10% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 57.90% were married couples living together, 7.90% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.20% were non-families. 27.10% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.90% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.39 and the average family size was 2.89.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 25.80% under the age of 18, 5.60% from 18 to 24, 24.00% from 25 to 44, 27.90% from 45 to 64, and 16.80% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females there were 99.30 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.10 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $32,560, and the median income for a family was $37,159. Males had a median income of $31,843 versus $22,253 for females. The per capita income for the county was $16,794. About 11.20% of families and 13.70% of the population were below the poverty line, including 16.60% of those under age 18 and 10.20% of those age 65 or over.

2000 U.S. Census statistics for Grant County show that the total workforce for Grant County was 3,800, or 62% of the total population over age 16. These people were employed as follows:

56.9% private wage/salaried positions; 14.7% private self-employed (not incorporated business); 0.8% private unpaid family workers; 27.6% public employees (municipal, county, state, federal governments);

By industry: 20.6% education, health, social services; 17.3% agriculture, forestry, mining; 10.0% manufacturing; 9.8% retail trade; 7.6% arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodations, and food; 6.9% public administration; 6.5% construction; 5.9% other services; 5.1% transportation, warehousing, utilities; 4.1% professional, administrative, and waste management; 3.1% finance, insurance, real estate, leasing; 1.7% information; 1.5% wholesale trade;

Communities

[edit]Cities

[edit]- Canyon City (county seat)

- Dayville

- Granite

- Greenhorn

- John Day

- Long Creek

- Monument

- Mount Vernon

- Prairie City

- Seneca

Unincorporated communities

[edit]Politics

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (June 2017) |

Like the other counties in eastern Oregon, the majority of registered voters who are affiliated with a political party in Grant County are members of the Republican Party. George W. Bush's performance here in 2000 marked the strongest of any Republican in the county, carrying just over 80% of Grant's votes in it. In the 2008 presidential election, 70.97% of Grant County voters voted for Republican John McCain, while 26.05% voted for Democrat Barack Obama and 3.94% of voters either voted for a Third Party candidate or wrote in a candidate.[16] These numbers show a small but definite shift towards the Democratic candidate when compared to the 2004 presidential election, in which 78.9% of Grant County voters voted for George W. Bush, while 19.2% voted for John Kerry, and 1.9% of voters either voted for a Third Party candidate or wrote in a candidate.[17] The 2008 presidential election, however, was the last time a Democratic nominee won over 1,000 votes in the county.

In the 2020 election, the county had shifted back to the Republican candidate Donald Trump, who received 77.28% of the votes, compared to Joseph Biden's share of 20.17%. The remaining 2.55% of voters chose either a Third Party candidate or wrote in a candidate.[18]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 3,545 | 77.13% | 929 | 20.21% | 122 | 2.65% |

| 2016 | 3,210 | 73.96% | 739 | 17.03% | 391 | 9.01% |

| 2012 | 2,926 | 74.81% | 853 | 21.81% | 132 | 3.38% |

| 2008 | 2,785 | 71.25% | 1,006 | 25.74% | 118 | 3.02% |

| 2004 | 3,204 | 78.90% | 780 | 19.21% | 77 | 1.90% |

| 2000 | 3,078 | 80.03% | 589 | 15.31% | 179 | 4.65% |

| 1996 | 2,110 | 54.99% | 1,180 | 30.75% | 547 | 14.26% |

| 1992 | 1,496 | 37.53% | 1,135 | 28.47% | 1,355 | 33.99% |

| 1988 | 2,264 | 58.90% | 1,437 | 37.38% | 143 | 3.72% |

| 1984 | 2,695 | 66.69% | 1,344 | 33.26% | 2 | 0.05% |

| 1980 | 2,519 | 60.16% | 1,274 | 30.43% | 394 | 9.41% |

| 1976 | 1,640 | 51.15% | 1,393 | 43.45% | 173 | 5.40% |

| 1972 | 1,781 | 60.35% | 932 | 31.58% | 238 | 8.07% |

| 1968 | 1,632 | 58.00% | 934 | 33.19% | 248 | 8.81% |

| 1964 | 1,149 | 37.90% | 1,877 | 61.91% | 6 | 0.20% |

| 1960 | 1,697 | 54.13% | 1,438 | 45.87% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1956 | 1,822 | 59.10% | 1,261 | 40.90% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1952 | 1,941 | 61.66% | 1,190 | 37.80% | 17 | 0.54% |

| 1948 | 1,090 | 47.54% | 1,156 | 50.41% | 47 | 2.05% |

| 1944 | 1,006 | 45.67% | 1,072 | 48.66% | 125 | 5.67% |

| 1940 | 1,103 | 40.93% | 1,582 | 58.70% | 10 | 0.37% |

| 1936 | 697 | 28.00% | 1,436 | 57.69% | 356 | 14.30% |

| 1932 | 733 | 31.53% | 1,496 | 64.34% | 96 | 4.13% |

| 1928 | 1,411 | 74.03% | 469 | 24.61% | 26 | 1.36% |

| 1924 | 1,126 | 56.90% | 459 | 23.19% | 394 | 19.91% |

| 1920 | 1,310 | 68.59% | 497 | 26.02% | 103 | 5.39% |

| 1916 | 941 | 40.56% | 1,210 | 52.16% | 169 | 7.28% |

| 1912 | 418 | 30.74% | 413 | 30.37% | 529 | 38.90% |

| 1908 | 748 | 56.93% | 433 | 32.95% | 133 | 10.12% |

| 1904 | 1,007 | 67.81% | 316 | 21.28% | 162 | 10.91% |

Economy

[edit]With the discovery of gold near Canyon City in June 1862, and near Granite in July 1862, gold miners streamed into the area. The eminent geologist, Waldemar Lindgren, who visited the area in 1900, estimated that approximately $16 million in gold had been mined from the Canyon City area alone by that time. (In 1900, the value of gold was fixed at $20.67 per ounce, so that $16 million in gold would have been roughly 800,000 ounces—worth today [at $1,600 an ounce] about $1.28 Billion) Mining remained the dominant sector of the area's economy, with increasing lode-ore production annually, until October 1942 when the U. S. War Labor Board made gold mining illegal by Executive Order, Public Law L-208. This effectively led to several mining towns being abandoned and the demise of the mining industry in eastern Oregon and elsewhere; idle equipment was removed as scrap drives during World War II literally dismantled a great deal of the county's mining infrastructure. In Oregon, Grant County's gold production was second only to Baker County.

Because of the wealth of natural resources found in Grant County, agriculture, ranching, and timber industries naturally grew with and contributed to the development of the county. In the early days, sheep formed a large part of the agricultural base and the area boasted some of the largest sheep bands in the world, supplying a great volume of wool to, among others, the world-renowned Pendleton Wool Works in Pendleton. Cattle ranchers and sheep ranchers were often at odds and physical confrontations were not uncommon. By the 1920 and 1930s, however, cattle ranching became—and continues to be—the dominant sector of the agricultural industry. Crop farming, dairy production and orchards operated on small scales during the late 19th century and early 20th century, but declined during World War II due to changing market and labor pressures. The commercial timber industry in Grant County grew rapidly in the 1920s, and again during and after World War II. Livestock raising and timber harvesting remain important sectors of Grant County's economy, although the production and profitability of these industries has declined in recent years due mainly to political and expanding-market factors. Two wood-fired co-gen electric plants have been built in the county, one of which continues to operate in Prairie City.

Due mainly to federal land management policies and global market pressures affecting timber and agricultural production and extraction, the county has experienced the second highest unemployment rate in Oregon for more than 30 years. The county has experienced some growth in recreational activities (including hunting) and tourism, as well as cottage industry, but residents have struggled to develop new productive industries and to diversify their economy. Slightly more than a quarter of the county's workforce is employed by some level of government or public services.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 141.

- ^ "Grant County Government". gcoregonlive.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ Beale, Bob (October 4, 2003). "Environment & Nature News - Humungous fungus: world's largest organism? - 10/04/2003". abc.net.au Science Online. Archived from the original on August 31, 2016.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Counties: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 24, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 26, 2015. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ a b c "DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ "Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ "DP02 SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ "DP03 SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ "2008 Grant County Oregon Election Results". gcoregonlive2.com. Archived from the original on March 11, 2009.

- ^ "Grant County, Oregon detailed profile - houses, real estate, cost of living, wages, work, agriculture, ancestries, and more". www.city-data.com. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ "Oregon a state divided by Trump, Biden: county by county returns (updated)". www.oregonlive.vom. November 4, 2020. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "Voter Registration by County". sos.oregon.gov. Office of the Secretary of State of Oregon. April 10, 2009.

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Turnbull, George S. (1939). . . Binfords & Mort.