Shigeru Miyamoto

Shigeru Miyamoto | |

|---|---|

宮本 茂 | |

Miyamoto in 2015 | |

| Born | November 16, 1952 Sonobe, Kyoto, Japan |

| Alma mater | Kanazawa College of Art |

| Occupations |

|

| Employer | Nintendo (1977–present) |

| Notable work | |

| Title | General Manager of Nintendo EAD (1984–2015) Senior Managing Director at Nintendo (2002–2015) Representative Director at Nintendo (2002–present) Fellow at Nintendo (2015–present)[1] |

| Spouse | Yasuko Miyamoto |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | AIAS Hall of Fame Award (1998)[2] BAFTA Fellowship (2010) Person of Cultural Merit (2019) |

| Signature | |

| |

Shigeru Miyamoto (Japanese: 宮本 茂, Hepburn: Miyamoto Shigeru, born November 16, 1952) is a Japanese video game designer, producer and game director at Nintendo, where he serves as one of its representative directors as an executive since 2002. Widely regarded as one of the most accomplished and influential designers in video games, he is the creator of some of the most acclaimed and best-selling game franchises of all time, including Mario, The Legend of Zelda, Donkey Kong, Star Fox and Pikmin. More than 1 billion copies of games featuring franchises created by Miyamoto have been sold.

Born in Sonobe, Kyoto, Miyamoto graduated from Kanazawa Municipal College of Industrial Arts. He originally sought a career as a manga artist, until developing an interest in video games. With the help of his father, he joined Nintendo in 1977 after impressing the president, Hiroshi Yamauchi, with his toys.[3] He helped create art for the arcade game Sheriff,[4] and was later tasked with designing a new arcade game, leading to the 1981 game Donkey Kong.

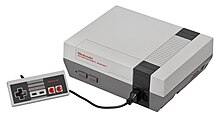

Miyamoto's games Super Mario Bros. (1985) and The Legend of Zelda (1986) helped the Nintendo Entertainment System dominate the console game market. His games have been flagships of every Nintendo video game console, from the arcade machines of the late 1970s to the present day. He managed Nintendo's Entertainment Analysis & Development software division, which developed many Nintendo games, and he played an important role in the creation of other influential games such as Pokémon Red and Blue (1996) and Metroid Prime (2002). Following the death of Nintendo president Satoru Iwata in July 2015, Miyamoto became acting president alongside Genyo Takeda until he was formally appointed "Creative Fellow" a few months later.[5]

Early life

Miyamoto was born on November 16, 1952, in the Japanese town of Sonobe, Kyoto Prefecture.[3] His parents were of "modest means", and his father taught English.[3]

From an early age, Miyamoto explored the natural areas around his home. He discovered a cave, and, after days of hesitation, went inside. His expeditions into the Kyoto countryside inspired his later work, particularly The Legend of Zelda, a seminal video game.[6]

In the early 1970s, Miyamoto graduated from Kanazawa Municipal College of Industrial Arts with a degree in industrial design.[3] He had a love for manga and initially hoped to become a professional manga artist before considering a career in video games.[7] He was influenced by manga's classic kishōtenketsu narrative structure,[8] as well as Western genre television shows.[9] He was inspired to enter the video game industry by the 1978 arcade hit Space Invaders.[10]

Career

1977–1984: Arcade beginnings and Donkey Kong

I feel that I have been very lucky to be a game designer since the dawn of the industry. I am not an engineer, but I have had the opportunities to learn the principles of game [design] from scratch, over a long period of time. And because I am so pioneering and trying to keep at the forefront, I have grown accustomed to first creating the very tools necessary for game creation.

— Shigeru Miyamoto (translated)[11]

In the 1970s, Nintendo was a relatively small Japanese company that sold playing cards and other novelties, although it had started to branch out into toys and games in the 1960s. Through a mutual friend, Miyamoto's father arranged an interview with Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi. After showing some of his toy creations, he was hired in 1977 as an apprentice in the planning department.[3]

Miyamoto helped create the art for the coin-operated arcade game, Sheriff.[4] He first helped the company develop a game after the 1980 release Radar Scope. The game achieved moderate success in Japan, but by 1981, Nintendo's efforts to break it into the North American video game market had failed, leaving them with a large number of unsold units and on the verge of financial collapse. Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi decided to convert unsold Radar Scope units into a new arcade game. He tasked Miyamoto with the conversion,[12]: 157 about which Miyamoto has said self-deprecatingly that "no one else was available" to do the work.[13] Nintendo's head engineer, Gunpei Yokoi, supervised the project.[12]: 158

Miyamoto imagined many characters and plot concepts, but eventually settled on a love triangle between a gorilla, a carpenter, and a woman. He meant to mirror the rivalry between comic characters Bluto and Popeye for the woman Olive Oyl, although Nintendo's original intentions to gain rights to Popeye failed.[3] Bluto evolved into an ape, a form Miyamoto claimed was "nothing too evil or repulsive".[14]: 47 This ape would be the pet of the main character, "a funny, hang-loose kind of guy".[14]: 47 Miyamoto also named "Beauty and the Beast" and the 1933 film King Kong as influences.[15]: 36 Miyamoto had high hopes for his new project, but lacked the technical skills to program it himself; instead, he conceived the game's concepts, then consulted technicians on whether they were possible. He wanted to make the characters different sizes, move in different manners, and react in various ways. However, Yokoi viewed Miyamoto's original design as too complex.[14]: 47–48 Yokoi suggested using see-saws to catapult the hero across the screen but this proved too difficult to program. Miyamoto next thought of using sloped platforms and ladders for travel, with barrels for obstacles. When he asked that the game have multiple stages, the four-man programming team complained that he was essentially asking them to make the game repeat, but the team eventually successfully programmed the game.[15]: 38–39 When the game was sent to Nintendo of America for testing, the sales manager disapproved of its vast differentiation from the maze and shooter games common at the time.[14]: 49 When American staffers began naming the characters, they settled on "Pauline" for the woman, after Polly James, wife of Nintendo's Redmond, Washington, warehouse manager, Don James. The playable character, initially "Jumpman", was eventually named for Mario Segale, the warehouse landlord.[16][17][14]: 109 These character names were printed on the American cabinet art and used in promotional materials. The staff also pushed for an English name, and thus it received the title Donkey Kong.[15]: 212

Donkey Kong was a success, leading Miyamoto to work on sequels Donkey Kong Jr. in 1982 and Donkey Kong 3 in 1983. In January 1983, the 1982 Arcade Awards gave Donkey Kong the Best Single-player video game award and the Certificate of Merit as runner-up for Coin-Op Game of the Year.[18] In his next game, he gave Mario a brother: Luigi. He named the new game Mario Bros. Yokoi convinced Miyamoto to give Mario some superhuman abilities, namely the ability to fall from any height unharmed. Mario's appearance in Donkey Kong—overalls, a hat, and a thick mustache—led Miyamoto to change aspects of the game to make Mario look like a plumber rather than a carpenter.[19] Miyamoto felt that New York City provided the best setting for the game, with its "labyrinthine subterranean network of sewage pipes". To date, games in the Mario Bros. franchise have been released for more than a dozen platforms.[20] Shortly after, Miyamoto also worked the character sprites and game design for the Baseball, Tennis, and Golf games on the NES.[21]

1985–1989: NES/Famicom, Super Mario Bros., and The Legend of Zelda

As Nintendo released its first home video game console, the Family Computer (rereleased in North America as the Nintendo Entertainment System), Miyamoto made two of the most popular titles for the console and in the history of video games as a whole: Super Mario Bros. (a sequel to Mario Bros.) and The Legend of Zelda (an entirely original title).[22]

In both games, Miyamoto decided to focus more on gameplay than on high scores, unlike many games of the time.[6] Super Mario Bros. largely took a linear approach, with the player traversing the stage by running, jumping, and dodging or defeating enemies.[23][24] It was a culmination of Miyamoto's gameplay concepts and technical knowledge drawn from his experiences of designing Donkey Kong, Mario Bros, Devil World (1984), the side-scrolling racing game Excitebike (1984), and the 1985 NES port of side-scrolling beat 'em up Kung-Fu Master (1984).[25] This culminated in his concept of a platformer set in an expansive world that would have the player "strategize while scrolling sideways" over long distances, have aboveground and underground levels, and have colorful backgrounds rather than black backgrounds.[26]

By contrast, Miyamoto employed nonlinear gameplay in The Legend of Zelda, forcing the player to think their way through riddles and puzzles.[27] The world was expansive and seemingly endless, offering "an array of choice and depth never seen before in a video game."[3] With The Legend of Zelda, Miyamoto sought to make an in-game world that players would identify with, a "miniature garden that they can put inside their drawer."[6] He drew his inspiration from his experiences as a boy around Kyoto, where he explored nearby fields, woods, and caves; each Zelda game embodies this sense of exploration.[6] "When I was a child," Miyamoto said, "I went hiking and found a lake. It was quite a surprise for me to stumble upon it. When I traveled around the country without a map, trying to find my way, stumbling on amazing things as I went, I realized how it felt to go on an adventure like this."[14]: 51 He recreated his memories of becoming lost amid the maze of sliding doors in his family home in Zelda's labyrinthine dungeons.[14]: 52 In February 1986, Nintendo released it as the launch game for the Nintendo Entertainment System's new Disk System peripheral.[28]

Miyamoto worked on various other different games for the Nintendo Entertainment System, including Ice Climber and Kid Icarus. He also worked on sequels to both Super Mario Bros and The Legend of Zelda. Super Mario Bros. 2, released only in Japan at the time, reuses gameplay elements from Super Mario Bros., though the game is much more difficult than its predecessor. Nintendo of America disliked Super Mario Bros. 2, which they found to be frustratingly difficult and otherwise little more than a modification of Super Mario Bros. Rather than risk the franchise's popularity, they canceled its stateside release and looked for an alternative. They realized they already had one option in Yume Kojo: Doki Doki Panic (Dream Factory: Heart-Pounding Panic), also designed by Miyamoto.[29] This game was reworked and released as Super Mario Bros. 2 (not to be confused with the Japanese game of the same name) in North America and Europe. The Japanese version of Super Mario Bros. 2 was eventually released in North America as Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels.[30]

The successor to The Legend of Zelda, Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, bears little resemblance to the first game in the series. The Adventure of Link features side-scrolling areas within a larger world map rather than the bird's eye view of the previous title. The game incorporates a strategic combat system and more RPG elements, including an experience points (EXP) system, magic spells, and more interaction with non-player characters (NPCs). Link has extra lives; no other game in the series includes this feature.[31] The Adventure of Link plays out in a two-mode dynamic. The overworld, the area where the majority of the action occurs in other The Legend of Zelda games, is still from a top-down perspective, but it now serves as a hub to the other areas. Whenever Link enters a new area such as a town, the game switches to a side-scrolling view. These separate methods of traveling and entering combat are one of many aspects adapted from the role-playing genre.[31] The game was highly successful at the time, and introduced elements such as Link's "magic meter" and the Dark Link character that would become commonplace in future Zelda games, although the role-playing elements such as experience points and the platform-style side-scrolling and multiple lives were never used again in the official series. The game is also looked upon as one of the most difficult games in the Zelda series and 8-bit gaming as a whole. Additionally, The Adventure of Link was one of the first games to combine role-playing video game and platforming elements to a considerable degree.[32]

Soon after, Super Mario Bros. 3 was developed by Nintendo Entertainment Analysis & Development; the game took more than two years to complete.[33] The game offers numerous modifications on the original Super Mario Bros., ranging from costumes with different abilities to new enemies.[33][34] Bowser's children were designed to be unique in appearance and personality; Miyamoto based the characters on seven of his programmers as a tribute to their work on the game.[33] The Koopalings' names were later altered to mimic names of well-known, Western musicians in the English localization.[33] In a first for the Mario series, the player navigates via two game screens: an overworld map and a level playfield. The overworld map displays an overhead representation of the current world and has several paths leading from the world's entrance to a castle. Moving the on-screen character to a certain tile will allow access to that level's playfield, a linear stage populated with obstacles and enemies. The majority of the game takes place in these levels.[23][24]

1990–2000: SNES, Nintendo 64, Super Mario 64, and Ocarina of Time

A merger between Nintendo's various internal research and development teams led to the creation of Nintendo Entertainment Analysis & Development (Nintendo EAD), which Miyamoto eventually headed. Nintendo EAD had approximately fifteen months to develop F-Zero, a launch game for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System.[35] Miyamoto worked through various games on the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, one of them Star Fox. For the game, programmer Jez San convinced Nintendo to develop an upgrade for the Super Nintendo, allowing it to handle three-dimensional graphics better: the Super FX chip.[36][37] Using this new hardware, Miyamoto and Katsuya Eguchi designed the Star Fox game with an early implementation of three-dimensional graphics.[38]

Miyamoto produced two major Mario games for the system. The first, Super Mario World, was a launch game. It features an overworld as in Super Mario Bros. 3 and introduces a new character, Yoshi, who appears in many other Nintendo games. The second Mario game for the system, Super Mario RPG, went in a somewhat different direction. Miyamoto led a team consisting of a partnership between Nintendo and Square; it took nearly a year to develop the graphics.[39] The story takes place in a newly rendered Mushroom Kingdom based on the Super Mario Bros. series.[40]

Miyamoto also created The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, the third entry in the series. Dropping the side-scrolling elements of its predecessor, A Link to the Past introduced to the series elements that are still commonplace today, such as the concept of an alternate or parallel world, the Master Sword, and other new weapons and items.[41][42]

Shigeru Miyamoto mentored Satoshi Tajiri, guiding him during the creation process of Pocket Monsters: Red and Green (released in English as Pokémon Red and Blue), the initial video games in the Pokémon series. He also acted as the producer for these games and worked on social gameplay concepts such as trading.[43] Pokémon would go on to be one of the most popular entertainment franchises in the world, spanning video games, anime, and various other merchandise.[44]

Miyamoto made several games for the Nintendo 64, mostly from his previous franchises. His first game on the new system, and one of its launch games, is Super Mario 64, for which he was the principal director. In developing the game, he began with character design and the camera system. Miyamoto and the other designers were initially unsure of which direction the game should take, and spent months to select an appropriate camera view and layout.[45] The original concept involved a fixed path much like an isometric-type game, before the choice was made to settle on a free-roaming 3D design.[45] He guided the design of the Nintendo 64 controller in tandem with that of Super Mario 64.[45]

Using what he had learned about the Nintendo 64 from developing Super Mario 64 and Star Fox 64,[9] Miyamoto produced his next game, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, leading a team of several directors.[46] Its engine was based on that of Super Mario 64 but was so heavily modified as to be a somewhat different engine. Individual parts of Ocarina of Time were handled by multiple directors—a new strategy for Nintendo EAD. However, when things progressed slower than expected, Miyamoto returned to the development team with a more central role assisted in public by interpreter Bill Trinen.[47] The team was new to 3D games, but assistant director Makoto Miyanaga recalls a sense of "passion for creating something new and unprecedented".[48] Miyamoto went on to produce a sequel to Ocarina of Time, known as The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask. By reusing the game engine and graphics from Ocarina of Time, a smaller team required only 18 months to finish Majora's Mask.[49]

Miyamoto worked on a variety of Mario series spin-offs for the Nintendo 64, including Mario Kart 64[50] and Mario Party.

2000–2011: GameCube, Wii, and DS

Miyamoto produced various games for the GameCube, including the launch game Luigi's Mansion. The game was first revealed at Nintendo Space World 2000 as a technical demo designed to show off the graphical capabilities of the GameCube.[51] Miyamoto made an original short demo of the game concepts, and Nintendo decided to turn it into a full game. Luigi's Mansion was later shown at E3 2001 with the GameCube console.[52] Miyamoto continued to make additional Mario spinoffs in these years. He also produced the 3D game series Metroid Prime, after the original designer Yokoi, a friend and mentor of Miyamoto's, died.[53] In this time he developed Pikmin and its sequel Pikmin 2, based on his experiences gardening.[3] He also worked on new games for the Star Fox, Donkey Kong, F-Zero, and The Legend of Zelda series on both the GameCube and the Game Boy Advance systems.[54][55][56] With the help of Hideo Kojima, he guided the developers of Metal Gear Solid: The Twin Snakes.[57] He helped with many games on the Nintendo DS, including the remake of Super Mario 64, titled Super Mario 64 DS, and the new game Nintendogs, a new franchise based on his own experiences with dogs.[58] At E3 2005, Miyamoto showed off Nintendogs with Tina Wood, where he promised to show her "a few more tricks" backstage.[59]

Miyamoto played a major role in the development of the Wii, a console that popularized motion control gaming, and its launch game Wii Sports, which helped show the capability of the new control scheme. Miyamoto went on to produce other titles in the Wii series, including Wii Fit. His inspiration for Wii Fit was to encourage conversation and family bonding.[3]

At E3 2004, Miyamoto unveiled The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess, appearing dressed as the protagonist Link with a sword and shield. Also released for the GameCube, the game was among the Wii's launch games and the first in the Zelda series to implement motion controls. He also helped with The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword, which featured more accurate motion controls. He also produced two Zelda titles for the Nintendo DS, The Legend of Zelda: Phantom Hourglass and The Legend of Zelda: Spirit Tracks. These were the first titles in the series to implement touch screen controls.

Miyamoto produced three major Mario titles for Wii from 2007 to 2010: Super Mario Galaxy,[60] New Super Mario Bros. Wii,[61] and Super Mario Galaxy 2.[62]

2011–present: Wii U, 3DS, Switch and other projects

Unlike in the 2000s in which he was involved on many projects as producer, Miyamoto's activities in development were less pronounced in that decade with Miyamoto only producing Luigi's Mansion: Dark Moon and Star Fox Zero.[63][64] Otherwise, Miyamoto was credited as General Producer, Executive Producer and Supervisor for most projects, which are positions with much less involvement in comparison to a producer.

Following the death of Nintendo president Satoru Iwata in July 2015, Miyamoto was appointed as an acting Representative Director, alongside Genyo Takeda.[65] He was relieved of this position in September 2015 when Tatsumi Kimishima assumed the role of the company's president. He was also appointed the position of "Creative Fellow" at the same time, providing expert advice to Kimishima as a "support network" alongside Takeda.[66] In his capacity as Creative Fellow, he provides feedback and guidance to game directors during development.[67][68]

In 2018, it was announced that Miyamoto would be working as a producer on The Super Mario Bros. Movie based on the Mario franchise by Illumination.[69]

Miyamoto was heavily involved with the design and construction of Super Nintendo World, a themed area featured at Universal Studios Japan and Universal Studios Hollywood and under construction at Universal Studios Singapore and Universal Epic Universe. Miyamoto oversaw the design and construction of the land and its attractions and acted as Nintendo's public representative on the land, hosting several promotional materials including a December 2020 Nintendo Direct in which he gave a tour of parts of the land.[70]

Development philosophy

People have paid me a lot of lip service, calling me a genius story teller or a talented animator, and have gone so far as to suggest that I try my hand at movies, since my style of game design is, in their words, quite similar to making movies. But I feel that I am not a movie maker, but rather that my strength lies in my pioneering spirit to make use of technology to create the best, interactive commodities possible, and use that interactivity to give users a game they can enjoy and play comfortably.

— Shigeru Miyamoto (translated)[11]

Miyamoto, and Nintendo as a whole, do not use focus groups. Instead, Miyamoto figures out if a game is fun for himself. He says that if he enjoys it, others will too.[3] He elaborates, citing the conception of the Pokémon series as an example, "And that's the point – Not to make something sell, something very popular, but to love something, and make something that we creators can love. It's the very core feeling we should have in making games."[71] Miyamoto wants players to experience kyokan; he wants "the players to feel about the game what the developers felt themselves."[3]

He then tests it with friends and family. He encourages younger developers to consider people who are new to gaming, for example by having them switch their dominant hand with their other hand to feel the experience of an unfamiliar game.[3]

Miyamoto's philosophy does not focus on hyper-realistic graphics, although he realizes they have their place. He is more focused on the game mechanics, such as the choices and challenges in the game.[3] Similar to how manga artists subverted their genre, Miyamoto hopes to subvert some of the basic principles he had popularized in his early games, retaining some elements but eliminating others.[3]

His game design philosophy typically prioritizes gameplay over storytelling. In a 1992 interview, he said "the important thing is that it feels good when you're playing it" and "that quality is not determined by the story, but by the controls, the sound, and the rhythm and pacing". However, he requires a "compatibility [between] the story and gameplay [because] a good story can smooth over that discrepancy and make it all feel natural".[72]

His use of real-time rendered cinematics (not prerendered video) serves both his own rapidly interactive development process with no rendering delays, and the player's interaction with the game's continuity. He prefers to change his games right until they are finalized, and to make "something unique and unprecedented". He prefers the game to be interactively fun rather than have elaborate film sequences, stating in 1999, "I will never make movie-like games";[71] therefore, the more than 90 total minutes of short cutscenes interspersed throughout Ocarina of Time[11] deliver more interactive cinematic qualities.[71][73] His vision mandates a rapid and malleable development process with small teams, as when he directed substantial changes to the overall game scenario in the final months of the development of Ocarina of Time. He said, "The reason behind using such a simple process, as I am sure you have all experienced in the workshop, is that there is a total limit on team energy. There is a limit to the work a team can do, and there is a limit to my own energy. We opted not to use that limited time and energy on pre-rendered images for use in cinema scenes, but rather on tests on other inter-active elements and polishing up the game".[11]

For these reasons, he opposes prerendered cutscenes.[11][9][71] Of Ocarina of Time, he says "we were able to make use of truly cinematic methods with our camera work without relying on [prerendered video]."[11]

Miyamoto has occasionally been critical of the role-playing game (RPG) genre. In a 1992 interview, when asked whether Zelda is an RPG series, he declined but classified it as "a real-time adventure"; he said he was "not interested in [games] decided by stats and numbers [but in preserving] as much of that 'live' feeling as possible", which he said "action games are better suited in conveying".[72] In 2003, he described his "fundamental dislike" of the RPG genre: "I think that with an RPG you are completely bound hand and foot, and can't move. But gradually you become able to move your hands and legs... you become slightly untied. And in the end, you feel powerful. So what you get out of an RPG is a feeling of happiness. But I don't think they're something that's fundamentally fun to play. With a game like that, anyone can become really good at it. With Mario though, if you're not good at it, you may never get good."[74] While critical of the RPG gameplay system,[74] he has occasionally praised certain aspects of RPGs, such as Yuji Horii's writing in the Dragon Quest series, the "interactive cinematic approach" of the Final Fantasy series,[72] and Shigesato Itoi's dialogue in the Mother series.[74]

Impact

Time called Miyamoto "the Spielberg of video games"[75] and "the father of modern video games,"[10] while The Daily Telegraph says he is "regarded by many as possibly the most important game designer of all time."[76] GameTrailers called him "the most influential game creator in history."[77] Miyamoto has significantly influenced various aspects of the medium. The Daily Telegraph credited him with creating "some of the most innovative, ground breaking and successful work in his field."[76] Many of Miyamoto's works have pioneered new video game concepts or refined existing ones. Miyamoto's games have received outstanding critical praise, some being considered the greatest games of all time.

Miyamoto's games have also sold very well, becoming some of the bestselling games on Nintendo consoles and of all time. As of 1999, his games had sold 250 million units and grossed billions of dollars.[76]

Calling him one of the few "video-game auteurs," The New Yorker credited Miyamoto's role in creating the franchises that drove console sales, as well as designing the consoles themselves. They described Miyamoto as Nintendo's "guiding spirit, its meal ticket, and its playful public face," noting that Nintendo might not exist without him.[3] The Daily Telegraph similarly attributed Nintendo's success to Miyamoto more than any other person.[76] Next Generation listed him in their "75 Most Important People in the Games Industry of 1995", elaborating that, "He's the most successful game developer in history. He has a unique and brilliant mind as well as an unparalleled grasp of what gamers want to play."[78]

Industry

Miyamoto's first major arcade hit Donkey Kong was highly influential. It spawned a number of other games with a mix of running, jumping, and vertical traversal.[79] Particularly novel, the vertical genre was initially referred to as "Donkey Kong-type" or "Kong-style",[80][79] before finalizing as "platform".[79] Earlier games either use storytelling or cutscenes, but Donkey Kong combines both to introduce the use of cutscenes to visually advance a complete story.[81] It has multiple, distinct levels that progress the storyline.[82][81] Computer and Video Games called Donkey Kong "the most momentous" release of 1981.[83]

Miyamoto's best known and most influential game, Super Mario Bros., "depending on your point of view, created an industry or resuscitated a comatose one".[3] The Daily Telegraph said it "set the standard for all future videogames".[76] G4 noted its revolutionary gameplay and its role in "almost single-handedly" rescuing the video game industry after the North American video game crash of 1983.[84] The game also popularized the side-scrolling video game genre. The New Yorker described Mario as the first folk hero of video games, with as much influence as Mickey Mouse.[3]

GameSpot featured The Legend of Zelda as one of the 15 most influential games of all time, for being an early example of open world, nonlinear gameplay, and for its introduction of battery backup saving, laying the foundations for later action-adventure games like Metroid and role-playing video games like Final Fantasy, while influencing most modern games in general.[85] In 2009, Game Informer called The Legend of Zelda "no less than the greatest game of all time" on their list of "The Top 200 Games of All Time", saying that it was "ahead of its time by years if not decades".[86]

At the time of the release of Star Fox, the use of filled, three-dimensional polygons in a console game was very unusual, apart from a handful of earlier titles.[87] Due to its success, Star Fox has become a Nintendo franchise, with five more games and numerous appearances by its characters in other Nintendo games such as the Super Smash Bros. series.

His game Super Mario 64 defined the field of 3D game design, particularly with its use of a dynamic camera system and the implementation of its analog control.[88][89][90] The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time's gameplay system introduced features such as a target lock system and context-sensitive buttons that have since become common elements in 3D adventure games.[91][92]

The Wii, which Miyamoto played a major role in designing, is the first wireless motion-controlled video game console.[3]

Critical reception

Miyamoto's games have received outstanding critical praise, and are widely considered among the greatest of all time.[3]

Games in Miyamoto's The Legend of Zelda series have received outstanding critical acclaim. A Link to the Past is a landmark game for Nintendo and is widely considered today to be one of the greatest video games of all time. Ocarina of Time is widely considered by critics and gamers alike to be one of the greatest video games ever made.[93][94][95][96] Ocarina of Time was listed by Guinness World Records as the highest-rated video game in history, citing its Metacritic score of 99 out of 100.[97] Twilight Princess was released to universal critical acclaim, and is the third highest-rated game for the Wii.[98] It received perfect scores from major publications such as CVG, Electronic Gaming Monthly, Game Informer, GamesRadar, and GameSpy.[99][100][101][102][103]

Critical analysis of Super Mario Bros. has been extremely positive, with many touting it as one of the best video games of all time.[104] In 2009, Game Informer put Super Mario Bros. in second place on its list of "The Top 200 Games of All Time", behind The Legend of Zelda, saying that it "remains a monument to brilliant design and fun gameplay".[86]

Super Mario 64 is acclaimed by many critics and fans as one of the greatest and most revolutionary video games of all time.[105][106][107][108][109][110]

According to Metacritic, Super Mario Galaxy and Super Mario Galaxy 2 are the highest- and second-highest-rated games, respectively, for the Wii.[98]

A 1995 article in Maximum stated that "in gaming circles Miyamoto's name carries far more weight than Steven Spielberg's could ever sustain."[111]

Commercial reception

More than 1 billion copies of games featuring franchises created by Miyamoto have been sold.[112]

Miyamoto's Mario series is, by far, the best-selling video game franchise of all time, selling over 500 million units. Super Mario Bros. is the sixth best-selling video game of all time. The game was the all-time bestselling video game for over 20 years until its lifetime sales were surpassed by Wii Sports.[113] Super Mario Bros., Super Mario Bros. 3, and Super Mario Bros. 2 were, respectively, the three bestselling games for the Nintendo Entertainment System. Levi Buchanan of IGN considered Super Mario Bros. 3's appearance in the film The Wizard as a show-stealing element, and referred to the movie as a "90-minute commercial" for the game.[114] Super Mario World was the bestselling game for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System.[115][116] Super Mario 64 was the bestselling Nintendo 64 game,[117] and as of May 21, 2003, the game had sold eleven million copies.[118] At the end of 2007, Guinness World Records reported sales of 11.8 million copies. As of September 25, 2007, it was the seventh best-selling video game in the United States with six million copies sold.[119] By June 2007, Super Mario 64 had become the second most popular game on Wii's Virtual Console, behind Super Mario Bros.[120] Super Mario Sunshine is the third best-selling GameCube game.[121]

The original game in The Legend of Zelda series is the fifth-bestselling game for the Nintendo Entertainment System. The Wind Waker is the fourth bestselling GameCube game. Twilight Princess was commercially successful. In the PAL region, which covers most of Asia, Africa, South America, Australia, New Zealand, and most of Western Europe, Twilight Princess is the bestselling Zelda game ever. During its first week, the game was sold with three out of every four Wii purchases.[122] The game had sold 4.52 million copies on the Wii as of March 1, 2008,[123] and 1.32 million on the GameCube as of March 31, 2007.[124]

The Mario Kart series is currently the most successful racing game franchise of all time. Mario Kart titles tend to be among the bestselling games for their respective consoles; Super Mario Kart is the third bestselling video game for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, Mario Kart 64 is the second bestselling Nintendo 64 game, Mario Kart: Double Dash is the second bestselling game for the GameCube,[121] and Mario Kart Wii is the second bestselling game for the Wii.

Miyamoto produced Wii Sports, another of the bestselling games of all time and part of the Wii series. Wii Fit designed by Miyamoto, was the third best selling console game not packaged with a console, with 22.67 million copies sold.[125]

Outside of video games, Miyamoto produced The Super Mario Bros. Movie, which ended up becoming the third-highest-grossing animated movie of all time, grossing $1.347 billion worldwide during its theatrical run as of July 14, 2023. It is also the highest-grossing film based on a video game (or video game series) by a huge margin, making it a huge statistical outlier; for context, the second-highest-grossing film based on a video game is Warcraft (2016), which grossed $900 million less, for a total of about $439 million.

Awards and recognition

[Miyamoto] approaches the games playfully, which seems kind of obvious, but most people don't. And he approaches things from the players' point of view, which is part of his magic.

The name of the main character of the PC game Daikatana, Hiro Miyamoto, is a homage to Miyamoto.[126] The character Gary Oak from the Pokémon anime series is named Shigeru in Japan and is the rival of Ash Ketchum (called Satoshi in Japan). Pokémon creator Satoshi Tajiri was mentored by Miyamoto.

In 1998, Miyamoto was honored as the first person inducted into the Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences' Hall of Fame.[127] In 2006, Miyamoto was made a Chevalier (knight) of the French Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Minister of Culture Renaud Donnedieu de Vabres.[128]

On November 28, 2006, Miyamoto was featured in TIME Asia's "60 Years of Asian Heroes".[129] He was later chosen as one of Time Magazine's 100 Most Influential People of the Year in both 2007[130] and also in 2008, in which he topped the list with a total vote of 1,766,424.[131] At the Game Developers Choice Awards, on March 7, 2007, Miyamoto received the Lifetime Achievement Award "for a career that spans the creation of Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda, and Donkey Kong to the company's recent revolutionary systems, Nintendo DS and Wii."[132] GameTrailers and IGN placed Miyamoto first on their lists for the "Top Ten Game Creators" and the "Top 100 Game Creators of All Time" respectively.[133][134]

In a survey of game developers by industry publication Develop, 30% of the developers, by far the largest portion,[3] chose Miyamoto as their "Ultimate Development Hero".[135] Miyamoto has been interviewed by companies and organizations such as CNN's Talk Asia.[136] He was made a Fellow of BAFTA at the British Academy Video Games Awards on March 19, 2010.[137] In 2012, Miyamoto was also the first interactive creator to be awarded the highest recognition in Spain, the Prince of Asturias Award, in the category of Communications and Humanities.[138][139]

Miyamoto was awarded Japan's Person of Cultural Merit in 2019 in recognition for his contributions towards Japan's video game industry.[140] He was the first person in the video game industry to receive the honor.[141]

Personal life

Miyamoto is married to Yasuko, and they have two children. In 2010, his son was 25 and working at an advertising agency, while his daughter was 23 and studying zoology at the time. His children played video games in their youth, but he also made them go outside. Although he can speak some English, he is not fluent and prefers to speak in Japanese for interviews.[3]

Miyamoto does not generally sign autographs, out of concern that he would be inundated. He also does not appear on Japanese television, so as to minimize his chance of being recognized. More foreign tourists than Japanese people approach him.[3]

Miyamoto spends little time playing video games in his personal time, preferring to play the guitar, mandolin, and banjo.[142] He avidly enjoys bluegrass music.[3] Miyamoto said in a 2016 interview that when he had his own family he took up gardening with his wife, which influenced other games that he was making at the time.[143] He has a Shetland Sheepdog named Pikku that provided the inspiration for Nintendogs.[144] He is also a semi-professional dog breeder.[145]

He has been quoted as stating, "Video games are bad for you? That's what they said about rock and roll."[146] Another quote that he was known to have had alleged said was "a delayed game is eventually good, but a rushed game is forever bad." In 2023, fans deduced that it was taken from a quote by Siobhan Beeman, who worked on the Wing Commander franchise at Origin Systems. She first uttered the phrase at GDC in 1996, or something close to it, “a game’s only late until it ships, but it sucks forever.” It somehow was misconstrued as a Miyamoto quote, circulating on the Internet for many years.[147][148][149]

Miyamoto enjoys rearranging furniture in his house, even late at night.[3] He also stated that he has a hobby of guessing the dimensions of objects, then checking to see if he was correct, and reportedly carries a measuring tape with him everywhere.[150] In December 2016, Miyamoto showcased his hobby on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, while also performing the Super Mario Bros. theme on guitar with The Roots during the same show.[151][152]

Selected works

References

- ^ This would later be converted to Super Mario Bros. 2 outside Japan.

- ^ "Annual Report 2019" (PDF). Nintendo. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 14, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ "D.I.C.E Special Awards". Archived from the original on November 4, 2016. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Paumgarten, Nick (December 12, 2010). "Master of Play". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on February 21, 2011.

- ^ a b "Iwata asks – Punch Out!". Nintendo. Archived from the original on January 11, 2010. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ "Notice Regarding Personnel Change of a Representative Director and Role Changes of Directors" (PDF). Nintendo. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 14, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Vestal, Andrew; Cliff O'Neill; Brad Shoemaker (November 14, 2000). "History of Zelda". GameSpot. Archived from the original on February 4, 2010. Retrieved September 30, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "E3 2011: Miyamoto speaks his mind". GameSpot. June 17, 2011. Archived from the original on June 19, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ "Nintendo's "kishōtenketsu" Mario level design philosophy explained". Eurogamer.net. March 17, 2015. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ a b c Miyamoto, Shigeru. "Iwata Asks: The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time 3D: Mr. Shigeru Miyamoto" (Interview). Interviewed by Satoru Iwata. Nintendo of America, Inc. Archived from the original on July 25, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Sayre, Carolyn (July 19, 2007). "10 Questions for Shigeru Miyamoto". Time. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f IGN Staff; Miyamoto, Shigeru (March 18, 1999). "GDC: Miyamoto Keynote Speech". Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ a b Kent, Steven L. (2002). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. New York: Random House International. ISBN 978-0-7615-3643-7. OCLC 59416169. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ^ Muldoon, Moira (December 2, 1998). "The father of Mario and Zelda". Salon. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sheff, David (1999). Game Over: Press Start to Continue: The Maturing of Mario. Wilton, Connecticut: GamePress.

- ^ a b c Kohler, Chris (June 10, 2014). "Nintendo's New Games Sound Great, Just Don't Expect Them Anytime Soon". WIRED. Archived from the original on June 23, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Kohler, Chris (February 17, 2012). "Game Life Podcast: When Jay Mohr Met Tomonobu Itagaki". Wired. Archived from the original on April 17, 2014. Retrieved September 28, 2024.

And so we thought, 'This guy [Segale] is a recluse. No one's ever actually met him.' So we thought, 'Wouldn't it be a great joke if we named this character Mario?' And so we said, 'That's great,' and we sent a telex to Japan, and that's how Mario got his name.

Interview with Don James starts at 51:16. Quotation occurs at 52:00. - ^ "Nintendo Treehouse Live - E3 2018 - Arcade Archives Donkey Kong, Sky Skipper". YouTube. Nintendo Everything. June 14, 2018. Archived from the original on October 3, 2023. Retrieved September 28, 2024.

Mr. Arakawa, who was the president, and myself looked at the character, and we had a landlord that happened to be named Mario as well, and we'd never met the guy, so we thought it'd be funny to name this main character Mario after our landlord in Southcenter. And that's actually how Mario got his name.

Quotation occurs at 2:25. - ^ "Electronic Games Magazine". Internet Archive. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ "IGN Presents The History of Super Mario Bros". IGN. November 8, 2007. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ Marcarelli, Eric. "Every Mario Game". Toad's Castle. Archived from the original on October 14, 2008. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

- ^ Kohler, Chris. "Miyamoto Spills Donkey Kong's Darkest Secrets, 35 Years Later". Wired. Archived from the original on October 16, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ Sao, Akinori. "The Legend of Zelda Developer Interview". Nintendo. Archived from the original on November 25, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- ^ a b Mean Machine Staff (October 1991). "Nintendo Review: Super Mario Bros. 3". Mean Machines. No. 13. EMAP. pp. 56–59. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2006.

- ^ a b Nintendo Power Staff (January–February 1990). "Previews: Super Mario Bros. 3". Nintendo Power. No. 10. Nintendo. pp. 56–59.

- ^ Gifford, Kevin. "Super Mario Bros.' 25th: Miyamoto Reveals All". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ Shigeru Miyamoto (December 2010). Super Mario Bros. 25th Anniversary – Interview with Shigeru Miyamoto #2 (in Japanese). Nintendo Channel. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Bufton, Ben (January 1, 2005). "Shigeru Miyamoto Interview". ntsc-uk. Archived from the original on May 10, 2006. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ "放課後のクラブ活動のように" [Like after-school club activities]. 社長が訊く. Nintendo Co., Ltd. November 19, 2009. Archived from the original on February 10, 2010. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

1986年2月に、ファミコンのディスクシステムと同時発売された、アクションアドベンチャーゲーム。 / An action-adventure game simultaneously released with the Famicom Disk System in February 1986.

- ^ Rosenberg, Adam. "'Super Mario Bros. 2' Interview Reveals A Strange, Vertical-Only Prototype". Archived from the original on October 20, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ^ McLaughlin, Rus (September 14, 2010). "IGN Presents The History of Super Mario Bros". IGN. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ a b Nintendo (December 1, 1988). Zelda II: The Adventure of Link (NES). Nintendo.

- ^ Thomas, Lucas M. (June 4, 2007). "Zelda II: The Adventure of Link Review". IGN. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "IGN Top 100 Games 2007: 39 Super Mario Bros. 3". IGN. 2007. Archived from the original on April 9, 2017. Retrieved January 25, 2009.

- ^ McLaughlin, Rus (November 8, 2007). "The History of the Super Mario Bros". IGN. Archived from the original on February 17, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ^ Anthony JC; Pete Deol (December 15, 2000). "Nintendo GameCube Developer Profile: EAD". N-Sider. IGN. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ^ Syd Bolton. "Interview with Jez San, OBE". Armchair Empire. Archived from the original on December 17, 2007. Retrieved December 28, 2007.

- ^ Baum, Dan. "Retrospective". Silicon Graphics Computer Systems. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ "Interview with Shigeru Miyamoto". Nintendo Power. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ^ Scott Pelland; Kent Miller; Terry Munson; Paul Shinoda (April 1996). "Epic Center". Nintendo Power. Vol. 83. Nintendo. p. 56.

Led by Mario creator Shigeru Miyamoto, teams at Nintendo Company Ltd. and Square Soft spent more than a year developing the visuals.

- ^ Pelland, Scott; Miller, Kent; Munson, Terry; Shinoda, Paul (October 1996). "Epic Center". Nintendo Power. No. 89. M. Arakawa, Nintendo of America, Inc. p. 60.

- ^ Arakawa, M. (1992). The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past Nintendo Player's Strategy Guide. Nintendo. ASIN B000AMPXNM.

- ^ Stratton, Bryan (December 10, 2002). The Legend of Zelda — A Link to the Past. Prima Games. ISBN 0-7615-4118-7.

- ^ "#Pokemon20: Nintendo's Shigeru Miyamoto". The Official Pokémon YouTube channel. Archived from the original on August 14, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- ^ Chua-Eoan, Howard; Tim Larimer (November 14, 1999). "Beware of the Pokemania". Time. New York City: Time Inc. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ a b c "The Making of Mario 64: Giles Goddard Interview". NGC Magazine (61). Future Publishing. December 2001. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- ^ "Sensei Speaks". IGN. January 29, 1999. Archived from the original on December 11, 2007. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ^ "Bill Trinen". Giant Bomb. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ "Inside Zelda Part 12: The Role of the Sidekick". Nintendo Power. Vol. 203. May 2006. pp. 76–78.

- ^ Yoon, Andrew (October 16, 2013). "Zelda's Eiji Aonuma on annualization, and why the series needs 'a bit more time'". Shacknews. GameFly. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- ^ "What's Next for Shigeru Miyamoto?". Next Generation. No. 26. Imagine Media. February 1997. p. 144.

- ^ "Luigi's Mansion preview". IGN. October 9, 2001. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- ^ "Pre-E3: Luigi's Mansion Disc and Controller Revealed". IGN. May 15, 2001. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ "Metroid Prime Roundtable QA". IGN. November 15, 2002. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2008.

- ^ Star Fox Assault Instruction Booklet. Nintendo of America. 2005. pp. 7, 29, 34–35.

- ^ Satterfield, Shane (March 28, 2002). "Sega and Nintendo form developmental partnership". GameSpot. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

The companies [Sega and Nintendo] are codeveloping two F-Zero games... Nintendo will be handling the publishing duties for the GameCube version while Sega will take on the responsibility of releasing the arcade game.

- ^ "Interview: Sega talk F-Zero". Arcadia magazine. N-Europe. May 17, 2002. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

We're [Amusement Vision] taking care of the planning and execution. Once things really begin to take shape, we'll turn to Nintendo for supervision.

- ^ "Metal Gear Solid Official". IGN. May 2003. Archived from the original on February 9, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2006.

- ^ Harris, Craig (May 11, 2004). "E3 2004: Hands-on: Super Mario 64 x4". IGN. Archived from the original on December 30, 2008. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- ^ "Nintendo E3 2005 Press Conference". YouTube. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ "How Super Mario Galaxy was Born". Nintendo. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Klepek, Patrick (June 2, 2009). "New Super Mario Bros. Achieve Shigeru Miyamoto's Dream: Multiplayer". G4. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ^ Gantayat, Anoop (May 18, 2010). "Super Mario Galaxy 2 Staff Quizzed by Iwata". andriasang. Archived from the original on May 19, 2010. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- ^ "Like a Shephard". Iwata Asks: Luigi's Mansion: Dark Moon. Nintendo of America. Archived from the original on July 25, 2015. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- ^ Zangari, Alex (December 18, 2014). "Miyamoto Discusses How the GamePad is Used in Star Fox for Wii U". Gamnesia. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ "Notification of Death and Personnel Change of a Representative Director (President)" (PDF). Nintendo Co. Ltd. July 12, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 13, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ "Notice Regarding Personnel Change of a Representative Director and Role Changes of Directors" (PDF). Nintendo Co. Ltd. September 14, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 14, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ Hussain, Tamoor (September 14, 2015). "Nintendo Appoints New President". GameSpot. Archived from the original on September 16, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ "How Shigeru Miyamoto Influenced Mario Odyssey's Development". Game Informer. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ^ a b "Shigeru Miyamoto will co-produce a 'Mario' animated movie". February 2018. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Miyamoto: Super Nintendo World will be "worth the wait"". Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Miyamoto, Shigeru (August 28, 1999). "Miyamoto Talks Dolphin at Space World '99" (Interview). Interviewed by Chris Johnston. GameSpot. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ a b c "The Future of RPGs – Developer Interviews". The Super Famicom (in Japanese). Vol. 3, no. 22. November 27, 1992. pp. 89–97. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- "The Future of RPGs – 1992 Developer Interviews". Shmuplations. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ Iwawaki, Toshio; Aonuma, Eiji; Kawagoe, Takumi; Koizumi, Yoshiaki; Osawa, Toru. "Iwata Asks: The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time 3D: Original Development Staff – Part 1" (Interview). Interviewed by Satoru Iwata. Nintendo of America, Inc. Archived from the original on July 25, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Nintendo Official Magazine". Nintendo Official Magazine. September 14, 2003. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- ^ Jackson, David S. (July 20, 1996). "The Spielberg of video games". Time. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "danielpemberton.com". danielpemberton.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ "GT Countdown Video – Top Ten Game Creators". GameTrailers. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ "75 Power Players: The Wizard". Next Generation. No. 11. November 1995. p. 50.

- ^ a b c Altice, Nathan (2015). "Chapter 2: Ports". I Am Error: The Nintendo Family Computer / Entertainment System Platform. MIT Press. pp. 53–80. ISBN 9780262028776.

- ^ "Gorilla Keeps on Climbing! Kong". Computer and Video Games. No. 26 (December 1983). November 16, 1983. pp. 40–1.

- ^ a b Lebowitz, Josiah; Klug, Chris (2011). Interactive Storytelling for Video Games: A Player-centered Approach to Creating Memorable Characters and Stories. Taylor & Francis. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-240-81717-0. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ "Donkey Kong". Retro Gamer. Future Publishing Limited. September 13, 2008. Archived from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ Glancey, Paul (1996). "The Complete History of Computer and Video Games". Computer and Video Games. pp. 15–6.

- ^ "G4TV's Top 100 Games – 1 Super Mario Bros". G4TV. 2012. Archived from the original on November 23, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ^ "15 Most Influential Games of All Time: The Legend of Zelda". GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 30, 2006. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ a b Staff (December 2009). "The Top 200 Games of All Time". Game Informer. No. 200. pp. 44–79. ISSN 1067-6392. OCLC 27315596.

- ^ News & Features Team (June 27, 2006). "Essential Games for the Animal Within". IGN. Archived from the original on November 27, 2006. Retrieved September 4, 2006.

- ^ "15 Most Influential Games of All Time". GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 30, 2006. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ "N64 Reader Tributes: Super Mario 64". IGN. Archived from the original on October 19, 2006. Retrieved October 21, 2006.

- ^ "The Essential 50 Part 36: Super Mario 64". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved October 21, 2006.

- ^ "The Essential 50 Part 40: The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- ^ Fahs, Travis (December 17, 2008). "IGN Presents the History of Zelda". IGN. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2009.

- ^ "Ocarina of Time Hits Virtual Console". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

the apex of 6-4bit[sic] gaming and oft-cited "Best Game Ever Made, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, has touched down over the pond for play on the Wii Virtual Console in most PAL-enabled regions.

- ^ "Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time". Metacritic. Archived from the original on November 21, 2010. Retrieved February 3, 2010. Metacritic here states that Ocarina of Time is "[c]onsidered by many to be the greatest single-player video game ever created in any genre".

- ^ "The Best Video Games in the History of Humanity". Filibustercartoons.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2010. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ Ryan, Michael E. (July 24, 2013) [2000]. "I Gotta Have This Game Machine!". Familypc. Vol. 7, no. 11. p. 112.

Considered by many to be the greatest video game ever

- ^ Guinness World Records. "Guinness World Records Gamer's Edition – Records – Nintendo". Archived from the original on April 5, 2008.

- ^ a b "Highest and Lowest Scoring Games". Metacritic. Archived from the original on September 8, 2013. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ Parish, Jeremy (November 16, 2006). "1up's Wii Review: Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- ^ Parish, Jeremy (January 2007). "The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess review". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Vol. 211. pp. 56–58.

- ^ Reiner, Andrew. "The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess". Game Informer. Archived from the original on August 1, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2006.

- ^ Williams, Bryn (November 13, 2006). "The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess Review". GameSpy. Archived from the original on December 2, 2006. Retrieved December 5, 2006.

- ^ "Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess Review. Wii Reviews". November 21, 2006. Archived from the original on July 26, 2008. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ^ Sources calling Super Mario Bros. one of the all-time best games include these:

- "G4TV's Top 100 Games". www.g4tv.com. G4. 2012. Archived from the original on November 23, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- "Top 100 Greatest Video Games Ever Made". www.gamingbolt.com. GamingBolt. April 19, 2013. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- "The Top 200 Games of All Time". Game Informer. No. 200. January 2010.

- "IGN's Top 100 Games of All Time". IGN. 2003. Archived from the original on December 7, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- "IGN's Top 100 Games of All Time". IGN. 2003. Archived from the original on December 7, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- "The Top 100 Games of All Time!". IGN. 2007. Archived from the original on December 3, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- "Top 100 Games Of All Time". IGN. 2015. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- "The 100 Greatest Video Games of All Time". slantmagazine.com. June 9, 2014. Archived from the original on July 12, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "All-TIME 100 Video Games". Time. November 15, 2012. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- Peckham, Matt; Eadicicco, Lisa; Fitzpatrick, Alex; Vella, Matt; Patrick Pullen, John; Raab, Josh; Grossman, Lev (August 23, 2016). "The 50 Best Video Games of All Time". Archived from the original on August 30, 2016. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- Polygon Staff (November 27, 2017). "The 500 Best Video Games of All Time". Polygon.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- "The Top 300 Games of All Time". Game Informer. No. 300. April 2018.

- ^ "IGN's Top 100 Games". IGN. 2003. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ^ "IGN's Top 100 Games". IGN. 2005. Archived from the original on March 1, 2010. Retrieved February 11, 2006.

- ^ "IGN's Top 100 Games of All Time". IGN. 2007. Archived from the original on February 16, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ^ "Top 100 Games of All Time". Game Informer. August 2001. p. 36.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Computer Games of All Time". Yahoo! Games. Archived from the original on November 27, 2011. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ^ "Fall 2005: 10-Year Anniversary Contest — The 10 Best Games Ever". GameFAQs. Archived from the original on February 20, 2007. Retrieved January 26, 2007.

- ^ "Mario No Dinosaur". Maximum: The Video Game Magazine. No. 1. October 1995. pp. 138–140.

- ^ MacDonald, Keza (December 30, 2023). "Nintendo's design guru Shigeru Miyamoto: 'I wanted to make something weird'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on February 17, 2024. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ "Getting That "Resort Feel"". Iwata Asks: Wii Sports Resort. Nintendo. p. 4. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016.

As it comes free with every Wii console outside Japan, I'm not quite sure if calling it "World Number One" is exactly the right way to describe it, but in any case it's surpassed the record set by Super Mario Bros., which was unbroken for over twenty years.

- ^ Buchanan, Levi (June 18, 2008). "The 90-Minute Super Mario Bros. 3 Commercial". IGN. Archived from the original on December 15, 2008. Retrieved January 25, 2009.

- ^ "1990". The Nintendo Years. Next-Gen.biz. June 25, 2007. p. 2. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved June 27, 2007.

- ^ "Mario Sales Data". Archived from the original on October 1, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ Craig Glenday, ed. (March 11, 2008). "Hardware: Best-Sellers by Platform". Guinness World Records Gamer's Edition 2008. Guinness World Records. Guinness. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-904994-21-3.

- ^ "All Time Top 20 Best Selling Games". Ownt.com. May 23, 2005. Archived from the original on February 21, 2006. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- ^ Sidener, Jonathan (September 25, 2007). "Microsoft pins Xbox 360 hopes on 'Halo 3' sales". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ^ Thorsen, Tor (June 1, 2007). "Wii VC: 4.7m downloads, 100 games". GameSpot. Archived from the original on June 5, 2009. Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- ^ a b O'Malley, James (September 11, 2015). "30 Best-Selling Super Mario Games of All Time on the Plumber's 30th Birthday". Gizmodo. Univision Communications. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ Sinclair, Brendan (November 27, 2006). "Over 600,000 Wiis served". GameSpot. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ^ "Million-Seller Titles of NINTENDO Products" (PDF). Nintendo. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 10, 2008. Retrieved May 1, 2008.

- ^ "Supplementary Information about Earnings Release" (PDF). Nintendo. April 27, 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- ^ "Nintendo Top Selling Software Sales Units: Wii". Nintendo. March 31, 2012. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ "A Hardcore Elegy for Ion Storm". Salon.com. p. 5. Archived from the original on December 6, 2006. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- ^ "Miyamoto Will Enter Hall of Fame". GameSpot. May 12, 1998. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

- ^ François Bliss de la Boissière (March 15, 2006). "From Paris with Love: de Chevalier dans l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres". Archived from the original on November 12, 2009. Retrieved August 25, 2009.

- ^ Wright, Will (November 13, 2006). "Shigeru Miyamoto: The video-game guru who made it O.K. to play". TIME Magazine. Archived from the original on June 14, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2006.

- ^ Wendel, Johnathan (May 3, 2007). "The TIME 100 (2007) – Shigeru Miyamoto". TIME Magazine. Archived from the original on November 12, 2011. Retrieved May 3, 2007.

- ^ "Who is Most Influential? – The 2008 TIME 100 Finalists". TIME Magazine. April 1, 2008. Archived from the original on February 3, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ Carless, Simon (February 12, 2007). "2007 Game Developers Choice Awards To Honor Miyamoto, Pajitnov". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on March 7, 2007. Retrieved February 12, 2007.

- ^ "Top Ten Game Creators". Gametrailers.com. Archived from the original on February 18, 2010. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ "Top 100 Game Creators of all Time". IGN. Archived from the original on April 2, 2010. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ Funk, John (June 15, 2009). "Miyamoto Is Developers' Hero". The Escapist. Archived from the original on February 6, 2010. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ Rao, Anjali. "Shigeru Miyamoto Talk Asia Interview". CNN. Archived from the original on April 1, 2009. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ Beaumont, Claudine (February 24, 2010). "Shigeru Miyamoto honoured by Bafta". London Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group. Archived from the original on March 12, 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ "Shigeru Miyamoto, Prince of Asturias Award for Communication and Humanities". Fundación Príncipe de Asturias. May 23, 2012. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Brice, Katherine (March 24, 2010). "Miyamoto nominated for top Spanish honour". GamesIndustry.biz. Eurogamer Network. Archived from the original on June 9, 2010. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ Taylor, Haydn (October 29, 2019). "Shigeru Miyamoto recognised with Japanese cultural award". GamesIndustry.biz. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ Allen Kim (October 29, 2019). "'Mario Bros.' creator Shigeru Miyamoto to be given one of Japan's highest honors". CNN. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ^ "Shigeru Miyamoto Developer Bio". MobyGames. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- ^ Shigeru Miyamoto's childhood influences on game design, archived from the original on February 25, 2023, retrieved February 25, 2023

- ^ Totilo, Stephen (September 27, 2005). "Nintendo Fans Swarm Mario's Father During New York Visit". MTV. Archived from the original on September 22, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- ^ Gibson, Ellie (August 23, 2005). "Nintendogs Interview // DS // Eurogamer". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- ^ ThinkExist.com Quotations. "Shigeru Miyamoto quotes". Thinkexist.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ Game Central. "Shigeru Miyamoto never said his most famous quote reveals new research". Metro. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ rawmeatcowboy. "Miyamoto's "delayed game" quote appears to be misattributed". Go Nintendo. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ Yin-Poole, Wesley. "Did Miyamoto Really Say "A Delayed Game Is Eventually Good, but a Rushed Game Is Forever Bad?"". IGN. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ Good, Owen (October 14, 2009). "Miyamoto's Secret Hobby: Measuring Stuff". Kotaku. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- ^ Good, Owen S. (December 10, 2016). "Watch Shigeru Miyamoto measure things for The Tonight Show". Polygon. Archived from the original on December 10, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Ricker, Thomas (December 8, 2016). "Watch Miyamoto play the Super Mario Bros theme song with The Roots". The Verge. Archived from the original on December 10, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ a b "Wii Official Site at Nintendo". Us.wii.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "Donkey Kong – Credits". allgame. October 3, 2010. Archived from the original on June 29, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Staff (April 2010). "The Man Behind Mario". GamesTM. No. 95. pp. 64–69.

- ^ "Retroradar: Discovering Sky Skipper". Retro Gamer. No. 170. July 2017. pp. 6–7.

- ^ "Donkey Kong Jr. Tech Info - GameSpot.com". archive.ph. July 30, 2012. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ^ "Mario Bros. Tech Info". Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ "Donkey Kong 3 Tech Info". Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ a b Kohler, Chris. "Miyamoto Spills Donkey Kong's Darkest Secrets, 35 Years Later". Wired. Archived from the original on June 22, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Yamashita, Akira (January 8, 1989). "Shigeru Miyamoto Interview: Profile of Shigeru Miyamoto". Micom BASIC (in Japanese). No. 1989–02. [Famicom (as director & game designer) – Hogan's Alley, Excitebike, Super Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda, Wild Gunman, Duck Hunt, Devil World, Spartan X]

- ^ "Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels Tech Info". Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ^ "Nintendo Switch: The Evoulution of Gaming". handmadewritings. October 31, 2016. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "Yume Kōjō: Dokidoki Panic credits (NES, 1987)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Knorr, Alyse (April 27, 2016). "The Making (And Legacy) Of Super Mario Bros. 3". Kotaku. G/O Media. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ a b "Interview with Shigeru Miyamoto". Nintendo Power. January 1997. Archived from the original on December 21, 2008. Retrieved December 2, 2008.

- ^ Nintendo (August 6, 1995). BS Zelda no Densetsu (Satellaview) (in Japanese) (Aug 95 ed.). St.GIGA.

Credits: オリジナル ゲームデザイン – 宮本 茂

- ^ "Pokémon Red Version (Game Boy, 1998) credits". MobyGames. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Pokémon Blue Version (Game Boy, 1998) credits". MobyGames. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Super Mario 64 – Credits". allgame. October 3, 2010. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "Wave Race 64: Kawasaki Jet Ski (1996)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Pokémon Snap (Nintendo 64, 1999) credits". MobyGames. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Paper Mario (Nintendo 64, 2000) credits". MobyGames. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask (2000)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Pikmin (2001)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Super Mario Sunshine credits (GameCube, 2002)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ "Metroid Prime (GameCube, 2002) credits". MobyGames. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker credits (GameCube, 2002)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ "Pikmin 2 credits (GameCube, 2004)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ "Nintendogs (2005)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess (Wii, 2006) credits". MobyGames. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Wii Sports (Wii, 2006) credits". MobyGames. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Super Mario Galaxy". November 12, 2007. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021 – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ "The Boar". theboar.org. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Wii Fit (2007)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Super Mario Galaxy 2 credits (Wii, 2010)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ "The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword credits (Wii, 2011)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Iwata, Satoru. "Asking Mr. Miyamoto Right Before Release". Iwata Asks. Nintendo. Archived from the original on July 25, 2015. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ^ "Pikmin 3 credits (Wii U, 2013)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ "Super Mario 3D World credits (Wii U, 2013)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ "The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds credits (Nintendo 3DS, 2013)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ "Super Mario Maker (Wii U, 2015) credits". MobyGames. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Star Fox Zero (2016)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ Otero, Jose (September 9, 2016). "11 Things We Learned About Super Mario Run". ign.com. Archived from the original on September 10, 2016. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ "The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017) credits". MobyGames. Archived from the original on July 23, 2023. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ "Super Mario Odyssey (2017) credits". MobyGames. Archived from the original on July 23, 2023. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ Bailey, Kat (February 20, 2023). "Interview: Shigeru Miyamoto Opens Up About Super Nintendo World and Nintendo's Future". IGN. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom (2023) credits". MobyGames. Archived from the original on July 23, 2023. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ "'Legend of Zelda' Live-Action Film in Development From Nintendo and 'Maze Runner' Director Wes Ball". Variety. November 7, 2023. Archived from the original on November 7, 2023. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

External links

- Shigeru Miyamoto at IMDb

- Shigeru Miyamoto on Nintendo Miiverse

- "Master of Play" profile in the New Yorker, December 20, 2010

- New York Times profile, May 25, 2008

- Video profile of Shigeru Miyamoto at the Wayback Machine (archived July 15, 2011) from the digital TV series Play Value

- Shigeru Miyamoto

- 1952 births

- 20th-century Japanese artists

- 21st-century Japanese artists

- Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences Hall of Fame inductees

- BAFTA fellows

- Chevaliers of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres

- Game Developers Conference Lifetime Achievement Award recipients

- Golden Joystick Award winners

- Japanese animated film producers

- Japanese video game designers

- Japanese video game directors

- Japanese video game producers

- Living people

- Nintendo people

- People from Kyoto Prefecture

- Persons of Cultural Merit

- Japanese video game artists