Humphrey Jennings

Humphrey Jennings | |

|---|---|

Jennings in Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey, suggesting a shot to Chick Fowle of the Crown Film Unit | |

| Born | Frank Humphrey Sinkler Jennings 19 August 1907 Walberswick, Suffolk, England |

| Died | 24 September 1950 (aged 43) Poros, Greece |

| Alma mater | Pembroke College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Documentary filmmaker |

| Known for | World War II film propaganda |

Frank Humphrey Sinkler Jennings (19 August 1907 – 24 September 1950) was an English documentary filmmaker and one of the founders of the Mass Observation organisation. Jennings was described by film critic and director Lindsay Anderson in 1954 as "the only real poet that British cinema has yet produced".[1]

Early life and career

[edit]Born in Walberswick, Suffolk, Jennings was the son of Guild Socialists, an architect father and a painter mother. He was educated at the Perse School and later read English at Pembroke College, Cambridge. When not studying, he painted and created advanced stage designs and was the founder-editor of Experiment in collaboration with William Empson and Jacob Bronowski.

After graduating with a starred First Class degree in English, Jennings undertook post-graduate research on the poet Thomas Gray, under the supervision of a predominantly absent I. A. Richards, who was teaching abroad. After abandoning what looked like being a successful academic career, Jennings undertook a number of jobs including photographer, painter and theatre designer. He joined the GPO Film Unit, then under John Grierson, in 1934, largely it is thought because Jennings needed the income after the birth of his first daughter, rather than from a strong interest in filmmaking. Relations with his colleagues were difficult; they saw him as something of a dilettante, but he did form a friendship with Alberto Cavalcanti.

In 1936, Jennings helped with the organisation of the 1936 Surrealist Exhibition in London, in association with André Breton, Roland Penrose and Herbert Read.[2] It was at about this time that Jennings, along with Charles Madge and Tom Harrisson, helped to found Mass Observation and co-edited with Madge the text May the Twelfth, a montage of extracts from observer reports of the 1937 coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth for Mass Observation. A fiftieth-anniversary edition of this text was published in 1987 by Faber.

In 1938, he edited an issue of the London Bulletin[3] which included a "collection of texts on the Impact of the Machine" and he used this material to prepare a series of talks to miners in the Swansea Valley while making The Silent Village several years later. This prompted him to add more material and he obtained a contract from Routledge to prepare it for publication as a book; he worked on it fitfully and thought it was almost ready just before his death. His daughter, Mary-Louise, asked Charles Madge to assist in finally editing it for publication in 1985 as Pandaemonium, 1660–1886: The Coming of the Machine as Seen by Contemporary Observers. The book was cited by writer Frank Cottrell Boyce as an influence in the London 2012 Olympics Opening Ceremony, with an early section of the ceremony named after it.[4]

The war years

[edit]The GPO Film Unit became the Crown Film Unit in 1940, a film-making propaganda arm of the Ministry of Information, and Jennings joined the new organisation.

Jennings only feature-length film, the 70-minute Fires Were Started (1943), also known as I Was A Fireman, details the work of the Auxiliary Fire Service in London. It blurs the lines between fiction and documentary because the scenes are re-enactments. This film, which uses techniques such as montage, is considered one of the classics of the genre.

His films are otherwise shorts, inclusively patriotic in sentiment and very British in their sensibility, such as: Spare Time (1939), London Can Take It! (1940), Words for Battle (1941), A Diary for Timothy (with a narration written by E.M. Forster, 1945), The Dim Little Island (1948) and Family Portrait (his last completed film, which tells of the Festival of Britain, 1950). Co-directed with Stewart McAllister, Jennings' best remembered short film is Listen to Britain (1942). Excerpts are often seen in other documentaries, especially portions of one of the concerts given by Dame Myra Hess in the National Gallery while its collection was evacuated for safe-keeping.

Personal life

[edit]Jennings married Cicely Cooper in 1929. The couple had two daughters. He was also associated with the American writer Emily Coleman and the American heiress Peggy Guggenheim in the 1930s.[5] He died in Poros, Greece,[6] in a fall on the cliffs of the Greek island while scouting locations for a film on post-war healthcare in Europe.

Reputation

[edit]

Humphrey Jennings' reputation always remained very high among filmmakers, but had faded among others. After 2001 this situation was partly rectified: firstly by the feature-length documentary by Oscar-winning documentary-maker Kevin Macdonald, Humphrey Jennings: The Man Who Listened to Britain (made by Figment Films in 2002 for British television's Channel 4); and secondly by Kevin Jackson's 450-page biography Humphrey Jennings (Picador, 2004). In 2003 two of his films, Listen to Britain and Spare Time, were included in the Tate Britain retrospective, A Century of Artists' Film in Britain which featured the work of over one hundred filmmakers. The Macdonald documentary is included in the Region 2 DVD of I Was a Fireman (Fires Were Started) released by Film First in 2008. An earlier BBC documentary written and directed by Robert Vas is entitled Heart of Britain (1970).[7][8]

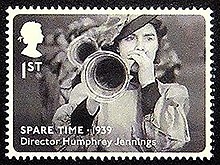

On 14 May 2014, his 1939 film Spare Time was one of those chosen to be commemorated in a set of Royal Mail stamps depicting notable GPO Film Unit films.[9][10]

The edition of BBC Radio 4's Great Lives, on 18 December 2018, was devoted to the life of Jennings.[11]

Filmography

[edit]As director

[edit]- Post-Haste (1934)

- Locomotives (1934)

- The Story of the Wheel (1934)

- Farewell Topsails (1937)

- Penny Journey (1938)

- Speaking from America (1938)

- The Farm (1938)

- English Harvest (1938)

- Making Fashion (1938)

- Spare Time (1939)

- SS Ionian (1939, a.k.a. Cargoes)

- The First Days (1939)

- Spring Offensive (1940)

- Welfare of the Workers (1940)

- London Can Take It! (1940, a.k.a. Britain Can Take It!)

- The Heart of Britain (1941, a.k.a. This Is England)

- Words for Battle (1941)

- Listen to Britain (co-director 1942)

- Fires Were Started (1943, a.k.a. I Was A Fireman)

- The Silent Village (1943)

- The True Story of Lili Marlene (1944)

- The Eighty Days (1944, a.k.a. V. 1)

- Myra Hess (1945)

- A Diary for Timothy (1945)

- A Defeated People (1946)

- The Cumberland Story (1947)

- The Dim Little Island (1949)

- Family Portrait (1950)

- The Good Life (completed by Graham Wallace 1951)

As producer/creative contributor

[edit]- Pett and Pott: A Fairy Story of the Suburbs (dir. Alberto Cavalcanti, 1934)

- The Birth of the Robot (dir. Len Lye, 1936)

References

[edit]- ^ Anderson, Lindsay (Spring 1954). "Only Connect: Some Aspects of the Work of Humphrey Jennings". Sight and Sound. 23 (4). Reprinted in Ryan, Paul, ed. (2004). Never Apologise: The Collected Writings. London: Plexus. pp. 358–365.

- ^ Sykes HD, Gascoyne D, Jennings H, et al. (1936). Surrealism: catalogue (PDF) (PDF). London: Women's Printing Society Ltd. p. 4.

- ^ David Hopkins (2018). "William Blake and British Surrealism: Humphrey Jennings, the Impact of Machines and the Case for Dada". Visual Culture in Britain. 19 (3): 312. doi:10.1080/14714787.2018.1522968. S2CID 192737893.

- ^ Boyce, Frank Cottrell (30 July 2012). "London 2012: opening ceremony saw all our mad dreams come true". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Morris, Desmond (2017). "Humphrey Jennings". Sixty-Nine Surrealists. Dark Windows Press. pp. 120–124. ISBN 978-1-909769-12-0.

- ^ Schneider, Steven Jay, ed. (2007). 501 Movie Directors. London: Cassell Illustrated. p. 164. ISBN 9781844035731. OCLC 1347156402.

- ^ '"'Heart of Britain (1970", exploreBFI

- ^ Bryony Dixon "Vas, Robert (1931–1978)", BFI screenonline reprinted from Directors in British and Irish Cinema

- ^ "Great British films celebrated on new Royal Mail stamps". BFI. 3 March 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ "British stamps honor films and GPO documentaries". Linns Stamp News. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - Great Lives, Tim Smit on Humphrey Jennings, Film Maker". BBC. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Aitken, Ian ed. Encyclopedia of the Documentary Film. Routledge (2005)

- Jackson, Kevin (Ed.). The Humphrey Jennings Film Reader (Carcanet, 1993)

- Jackson, Kevin. Humphrey Jennings (Picador, 2004).

- Merralls, James. Humphrey Jennings: A Biographical Sketch. Film Quarterly vol 15, no 2 (Winter 1961–62), pp. 29–34

- Winston, Brian. Fires Were Started- (BFI, 1999)

External links

[edit]- Humphrey Jennings at IMDb

- Bibliography of books and articles about Jennings via UC Berkeley Media Resources Center

- the BFI's "screenonline" site about Jennings

- Review of Kevin Jackson's Jennings biography

- Humphrey Jennings at Find a Grave

- 1907 births

- 1950 deaths

- Accidental deaths from falls

- Accidental deaths in Greece

- Alumni of Pembroke College, Cambridge

- Burials at the First Cemetery of Athens

- Civil servants in the Ministry of Information (United Kingdom)

- English documentary filmmakers

- English film directors

- Humphrey Jennings

- People educated at The Perse School

- People from Walberswick

- Propaganda film directors