Marshall Jewell

Marshall Jewell | |

|---|---|

Photo by Mathew Brady | |

| Chair of the Republican National Committee | |

| In office July 2, 1880 – February 10, 1883 | |

| Preceded by | J. Donald Cameron |

| Succeeded by | Dwight M. Sabin |

| 25th United States Postmaster General | |

| In office August 24, 1874 – July 12, 1876 | |

| President | Ulysses S. Grant |

| Preceded by | James Marshall |

| Succeeded by | James Tyner |

| United States Minister to Russia | |

| In office December 9, 1873 – July 19, 1874 | |

| President | Ulysses S. Grant |

| Preceded by | James Orr |

| Succeeded by | George Boker |

| 44th and 46th Governor of Connecticut | |

| In office May 16, 1871 – May 7, 1873 | |

| Lieutenant | Morris Tyler |

| Preceded by | James E. English |

| Succeeded by | Charles Ingersoll |

| In office May 5, 1869 – May 4, 1870 | |

| Lieutenant | Francis Wayland III |

| Preceded by | James E. English |

| Succeeded by | James E. English |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 20, 1825 Winchester, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Died | February 10, 1883 (aged 57) New Haven, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Political party | Whig (Before 1854) Republican (1854–1883) |

| Signature | |

Marshall Jewell (October 20, 1825 – February 10, 1883) was a manufacturer, pioneer telegrapher, telephone entrepreneur, world traveler, and political figure who served as 44th and 46th Governor of Connecticut, the US Minister to Russia, the 25th United States Postmaster General, and Republican Party National Chairman. Jewell, distinguished for his fine "china" skin, grey eyes, and white eyebrows, was popularly known as the "Porcelain Man".[1] As Postmaster General, Jewell made reforms and was intent on cleaning up the Postal Service from internal corruption and profiteering. Postmaster Jewell helped Secretary of the Treasury Benjamin H. Bristow shut down and prosecute the Whiskey Ring. President Grant, however, became suspicious of Jewell's loyalty after Jewell fired a Boston postmaster over non payment of a surety bond and asked for his resignation.[1]

A native of New Hampshire, Jewell was the son of a prominent tanner and currier. Having apprenticed in his father's tannery business,[2] Jewell moved to Boston where he learned the art of being a currier. In 1847, Jewell moved to Hartford where he worked for his father's business as a currier. Jewell stopped working as a currier and became a skilled telegrapher, where he worked in New York, Ohio, and Tennessee. Jewell was a Whig who supported the election of Zachary Taylor to the office of the presidency. Having supported Taylor, Jewell moved to Mississippi where he was elected General Superintendent of Telegraphers.[2] Jewell moved back to New York in 1849, and in 1850 he returned to his father's tannery business having entered into partnership with his father. Between 1859 and 1860, Jewell traveled to and visited Europe on business connected with the tannery firm, having returned to the United States during the onset of the American Civil War. In 1865 Jewell returned to Europe and traveled to Egypt and the Holy Land.[2]

Having returned to the United States, Jewell, a Republican, ran for Connecticut state senator in 1867; however, he failed to win the election.[3] In 1868, Jewell ran for the office of Connecticut Governor; however, he lost the election.[3] Jewell ran again the following year and was elected Governor of Connecticut in 1869, serving from 1869 until 1870, and was defeated in the 1870 election. Jewell was reelected to the governorship in 1871 and 1872, and served until 1873. In 1873, Jewell was appointed Consul to Russia by President Ulysses S. Grant and served until 1874 when he was appointed by President Grant as Postmaster General of the United States, a position he held until 1876. Jewell was also a presidential candidate at the 1876 Republican National Convention and served as the chairman of the Republican National Committee from 1880 until 1883. Having returned to Connecticut, Jewell became a wealthy merchant, having invested in the Hartford Evening Post and the Southern New England Telephone Company.[1][3] He died in 1883 in New Haven, Connecticut, and was interred at Cedar Hill Cemetery in Hartford, Connecticut.[4]

Early life and career

[edit]Marshall Jewell was born in Winchester, New Hampshire on October 25, 1825.[1] His father, Pliny Jewell, native of Hartford, was a prominent tanner and currier. His mother was Emily Alexander. His elder brother was named Harvey Jewell. The young Marshall received a limited education at common schools.[5] At an early age Jewell apprenticed for his father in the tannery business working as a day laborer until the age of 18. Jewell moved to Woburn where he learned the skill of being a currier.[5] Jewell returned to his father's tannery business in Hartford where he worked in the currier shop for two years.[1] In 1847, Jewell grew tired of the tannery business and having good business sense learned the telegraphy trade working in Boston, Rochester, and Akron.[5] As a highly skilled telegrapher, Jewell was put in charge of the Louisville and New Orleans telegraph line working in Columbia, Tennessee.[1][5]

Early political involvement

[edit]

In 1848, while working as a telegrapher, Jewell became interested in national politics becoming a Whig. Jewell supported Zachary Taylor for President of the United States. Jewell's political opinions would later draw him into the Republican Party formed in the mid-1850s[5] In 1849, Jewell returned north and was elected Superintendent of the telegraph line between Boston and New York living in New York City.[1][5]

Tanning partnership established

[edit]While Jewell was working as a telegrapher, Jewell's father Pliny's tanning business had increased substantially. Having left the telegraph business, moving back to Hartford, Jewell entered into partnership with his father's tanning and belting business on January 1, 1850.[1][5] Jewell, who had good business sense, for the next eight years increased his father's business and gained a positive reputation in the Hartford community.[1] Between 1852 and 1857 Jewell traveled widely throughout the United States to promote his manufactured leather product business.[5]

World travels and the American Civil War

[edit]From 1859 to 1860, Marshall went on a trip to Europe in order to expand his leather business. During the onset of the American Civil War Jewell purchased leather putting his business in a good position to gain government contracts.[5] During the Civil War, Jewell's tanning business flourished having supported the Northern war effort.[3] After the Civil War ended Jewell returned to Europe and extended his travels to Egypt and the Holy Land from 1865 to 1867.[1][5]

Governor of Connecticut

[edit]

Having returned from his extensive world travels abroad, in 1867, Jewell unsuccessfully ran for Connecticut state senator, having joined the Republican Party. In 1868, Jewell unsuccessfully ran for Governor of Connecticut. In 1869, Jewell was elected Governor of Connecticut having served until his defeat in 1870. Jewell was returned to office in the disputed election of 1871, and was last elected governor in 1872, having served three terms in office until 1873.[3] During Jewell's second term in office, Russian Grand Duke Alexis visited Washington, D.C., and Hartford, Connecticut. While in Hartford the Grand Duke stayed at Gov. Jewell's house. The Grand Duke was impressed by Jewell's ability to improve his status in the United States, having stated, "What! Is this the way Americans rise? from the tannery to the governor's chair?"[6]

U.S. Minister to Russia

[edit]On May 20, 1873, Ulysses S. Grant nominated Jewell as Minister to Russia, to replace James L. Orr. Jewell served with "marked ability" from May 29, 1873, to December 9, 1873.[2] While Minister to Russia, a prince from the Russian nobility became infatuated with a married American woman who was visiting St. Petersburg, having given her his family's royal diamonds. This created quite a scandal; however, Jewell investigated the matter and had the woman return the Russian diamonds to the Tsar's family.[1] Jewell, who was an observant man, noticed that inferior goods not made in the United States were falsely sold on the open Russian markets under an American name. Jewell appealed to the Russian government that this practice harmed authentic American trade with Russia. Jewell was able to negotiate a specific treaty that protected United States trademarks.[7]

While in Russia, Jewell, as a tanner, discovered that the Russians used birch tar to make the aromatic and hard-wearing Russia leather. Rather than keep this a secret for his own profit, Jewell sent a sample of the birch tar to the United States and American newspapers published how Russia leather was made.[8] Jewell was recalled from Minister to Russia when President Grant offered Jewell the office U.S. Postmaster General. Jewell had desired to hold a domestic office rather than an international office. Jewell's recall from Russia was a surprise to the American public, as he had served less than a year.[2]

U.S. Postmaster General

[edit]In 1874, a vacancy was created in President Grant's Cabinet when John A.J. Creswell resigned as U.S. Postmaster General. President Grant, who desired the position go to a New Englander, appointed Jewell U.S. Postmaster General in July 1874. Jewell, due to commitments as a Russian Minister and his return voyage to the United States, could not take office until August, while assistant Postmaster General, James William Marshall, served as acting U.S. Postmaster General until Jewell could take office.[2]

Reform efforts

[edit]Jewell took up the office of U.S. Postmaster with vigor, a man of many words and theories, having desired to reform the Postal Service from profiteering in lucrative postal contracts known as Star Routes. Having studied the European postal system, Jewell was the first post-master to establish a direct postal route service from New York City to Chicago.[5] Jewell wanted the Postal Service to be run like a business rather than through patronage. His ethical and progressive business practices, however, soon ran into conflict with those who wanted to the U.S. postal department to distribute patronage and lucrative contracts to brokers and mail route service providers.[5] Jewell often called meetings with his clerks giving them new instructions on reform. Jewell was noted to have said to his clerks, "We are cleaning up the department by degrees, and we are getting it found on business principles."[1] Postmaster Jewell aided and stood by Secretary of the Treasury Benjamin H. Bristow shut down and prosecute the notorious Whiskey Ring; a tax evasion scheme by whiskey distillers that depleted the U.S. Treasury millions of dollars.[9][5] Jewell was in favor of Bristow's presidential aspirations in 1876.[10]

Resignation

[edit]Washington, D.C., proved to be a challenge for Jewell's reforms of the Postal Service. During his tenure partisan politics caused Jewell to lose President Grant's support.[5] In one instance, Jewell fired Boston postmaster, William L. Burt, for non payment of a surety bond and replaced him with Edward C. Tobey on September 18, 1875. Burt, who would not let the issue settle had several conferences with President Grant one at Long Branch in 1875 and one at Washington, D.C., in 1876 to protest his removal. Jewell stated that although Burt was a capable Postmaster of Boston, he had given Burt ample time, five months, to have paid for the surety bond. One partisan broker complained that Jewell "ran the post-office as if it were a factory."[5] Following a Cabinet meeting in 1876, President Grant abruptly asked for Sec. Jewell's resignation without explanation. Jewell, who did not ask why Grant demanded his resignation, was shocked having believed he had the confidence of the President at the previous Cabinet meeting. President Grant, suspicious of any Cabinet members whom he was convinced were personally disloyal, believed that Jewell had been treacherous to his Administration and had conspired with another reformer, Secretary of the Treasury, Benjamin H. Bristow.[1]

Return to Hartford

[edit]After Jewell had been dismissed by President Grant as Postmaster, Jewell returned to Hartford who welcomed Jewell with open arms. Jewell devoted his time to his tanning business that had faltered while he had been away. Through a series of investments in the Hartford Evening Post and the Southern New England Telephone Company Jewell became a very wealthy man.[1]

1876 Republican Convention

[edit]

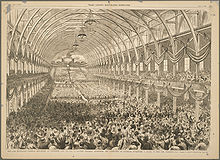

During the 1876 Republican National Convention held in Cincinnati, Ohio, Marshall Jewell was nominated by the State of Connecticut for President of the United States. Grant chose not to run and the Republicans did not choose to nominate him for a consecutive third term. Jewell was the first person from the State of Connecticut to be nominated at a national Republican Presidential Convention. On the first presidential ballot, Jewell received 11 votes, ten from Connecticut.[11] Jewell's name, however, was withdrawn from the remaining ballots. Benjamin Bristow also ran for the Republican presidential candidacy, but he could not get enough votes at the end of the balloting. Although Bristow was a frontrunner and had Jewell's support, he was considered controversial for his prosecution of the Whiskey Ring, a scandal that involved prominent Republican Party members. Instead, Rutherford B. Hayes, went on to win the Republican presidential nomination by receiving 384 votes on the seventh ballot.[12] Jewell was also nominated for Vice President of the United States by S.H. Russell from Texas; however, William A. Wheeler was unanimously nominated on the first ballot by 366 majority votes.[13] William Kellogg withdrew Jewell's name from the ballot after the votes cast were unanimously for Wheeler.[13] The state of Connecticut named Jewell on the 1876 Republican National Committee who elected Zachariah Chandler as chairman.[14]

Chairman of Republican Party

[edit]In 1879 Jewell accepted the appointment of National Chairman of the Republican Party having served to 1880. During the presidential election of 1880, Jewell's energetic approach to politics resulted in large part to the election of Republican candidate James A. Garfield to the office of President of the United States.[6]

Death, burial, and memorial

[edit]

Although considered a man of vitality in 1883, Jewell had contracted pneumonia that quickly took his life. When Jewell asked his doctor "How long does it take for a man to die?" His doctor responded, "In your condition, Governor, it is a matter of only a few hours." Marshall Jewell died on February 10, 1883, in Hartford, Connecticut.[6] Jewell was buried at Cedar Hill Cemetery on Valentine's Day, February 14, 1883. Flags were held at half mast on public and private buildings. The Connecticut Legislature suspended business and adjourned for the day. The Governors Guard guarded Jewell's body held in state at the Asylum Hill Congregational Church. Thousands of people viewed Jewell's body in state and paid their respects to the former Governor. Many prominent men attended Jewell's service, including former Secretary of the Treasury Benjamin Bristow, Postmaster Timothy O. Howe, and Secretary of Navy William E. Chandler.[15] A tall column pedestal and statue memorial monument with his family's name, "JEWELL", inscribed at the base, was placed near his burial site. Jewell's wife, Esther E Dickerson Jewell, died February 26, 1883, and was buried next to her husband Marshall Jewell at Cedar Hill Cemetery.

His daughter was Josephine Jewell Dodge, a prominent early childhood educator and anti-suffrage activist.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Chicago Daily Tribune (February 18, 1883), Marshall Jewell

- ^ a b c d e f New York Times (July 4, 1874), Appointment and Acceptance of the Hon. Marshall Jewell

- ^ a b c d e Miller Center (2012), Marshall Jewell (1874–1876): Postmaster General Archived May 8, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved May 24, 2012

- ^ "The Political Graveyard: Hartford County, Conn". Cedar Hill Cemetery. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved April 29, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Moody 1933, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Holloway (1885), Famous American Fortunes and the Men who Have Made Them, p. 446

- ^ Holloway, pp. 442-443

- ^ Holloway, p. 443

- ^ New England Historic Genealogical Society, p. 127

- ^ Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography 1887, p. 432.

- ^ Tweedy (1910). A history of the Republican national conventions from 1856 to 1908. pp. 155–157.

- ^ Tweedy 1910, p. 156

- ^ a b Tweedy 1910, pp. 157–158

- ^ Tweedy 1910, p. 158

- ^ New York Times (February 15, 1883), Laid at Rest.; Funeral of Ex-Gov. Marshall Jewell at Hartford.

- ^ "Josephine Marshall Jewell Dodge" in Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyer, eds., Notable American Women, 1607–1950, A Biographical Dictionary, vol. 2 (Harvard University Press 1971): 492-493. ISBN 9780674627345

Sources

[edit]- Moody, Robert E. (1933). Dumas Malone (ed.). Dictionary of American Biography Jewell, Marshall. New York City: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1887). Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography Jewell, Marshall. New York City: D. Appleton and Company. pp. 431–432.

- 1825 births

- 1883 deaths

- 19th-century American diplomats

- 19th-century American politicians

- Ambassadors of the United States to Russia

- Burials at Cedar Hill Cemetery (Hartford, Connecticut)

- Deaths from pneumonia in Connecticut

- Republican Party governors of Connecticut

- Grant administration cabinet members

- People from Winchester, New Hampshire

- Republican National Committee chairs

- United States postmasters general