Helvetic Republic

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Helvetic Republic | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1798–1803 | |||||||||||||||

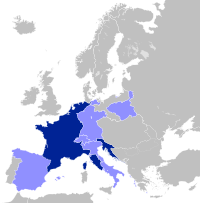

The Helvetic Republic, with borders according to the first Helvetic constitution of 12 April 1798. Modern Swiss borders are outlined in orange. | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Client state of France | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Aarau (1798) Lucerne (1798–1799) Bern (1799–1803)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Official languages | French, German, Italian[2][3] | ||||||||||||||

| Other languages | Romansh | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Directorial republic | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | French Revolutionary Wars | ||||||||||||||

• Confederation collapsed on French invasion | 5 March 1798 | ||||||||||||||

• Proclaimed | 12 April 1798 | ||||||||||||||

• Elections in Zürich | 14 April 1798 | ||||||||||||||

• Mutual defence treaty with France | 19 August 1798 | ||||||||||||||

• Diplomatic recognition by French allies | 19 September 1798 | ||||||||||||||

• Malmaison constitution | 29 May 1801 | ||||||||||||||

• Federal constitution | 27 February 1802 | ||||||||||||||

| 19 February 1803 | |||||||||||||||

| Currency | Swiss franc | ||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | CH | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Note: See below for a full list of predecessor states | |||||||||||||||

The Helvetic Republic (République helvétique (French), Helvetische Republik (German), Repubblica Elvetica (Italian), Republica helvetica (Romansh)) was a sister republic of France that existed between 1798 and 1803, during the French Revolutionary Wars. It was created following the French invasion and the consequent dissolution of the Old Swiss Confederacy, marking the end of the ancien régime in Switzerland.[4] Throughout its existence, the republic incorporated most of the territory of modern Switzerland, excluding the cantons of Geneva and Neuchâtel and the old Prince-Bishopric of Basel.[1]

The Swiss Confederacy, which until then had consisted of self-governing cantons united by a loose military alliance (and ruling over subject territories such as Vaud), was invaded by the French Revolutionary Army and turned into an ally known as the "Helvetic Republic". The interference with localism and traditional liberties was deeply resented, although some modernizing reforms took place.[5][6] Resistance was strongest in the more traditional Catholic cantons, with armed uprisings breaking out in spring 1798 in the central part of Switzerland. The French and Helvetic armies suppressed the uprisings, but opposition to the new government gradually increased over the years, as the Swiss resented their loss of local democracy, the new taxes, the centralization and the hostility to religion. Nonetheless, there were long-term effects to the Helvetic citizens.[7]

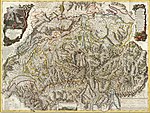

The Republic's name Helvetic, after the Helvetii, the Gaulish inhabitants of the Swiss Plateau in antiquity, was not an innovation; rather, the Swiss Confederacy had occasionally been dubbed Republica Helvetiorum in humanist Latin since the 17th century, and Helvetia, the Swiss national personification, made her first appearance in 1672.[citation needed] In Swiss history, the Helvetic Republic represents an early attempt to establish a centralized government in the country.

History

[edit]

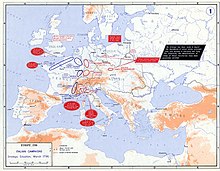

During the French Revolutionary Wars of the 1790s, the French Republican armies expanded eastward. In 1793, the National Convention had imposed friendship with the United States and the Swiss Confederation as the sole limit while delegating its powers in foreign policy to the Committee of Public Safety, but the situation changed when the more conservative Directoire took power in 1795 and Napoleon conquered Northern Italy in 1796. The French Republican armies enveloped Switzerland on the grounds of "liberating" the Swiss people, whose own system of government was deemed feudal, especially for annexed territories such as Vaud.

| History of Switzerland |

|---|

|

| Early history |

| Old Swiss Confederacy |

|

| Transitional period |

|

| Modern history |

|

| Timeline |

| Topical |

|

|

Some Swiss nationals, including Frédéric-César de La Harpe, had called for French intervention on these grounds. The invasion proceeded largely peacefully since the Swiss people failed to respond to the calls of their politicians to take up arms.

On 5 March 1798, French troops completely overran Switzerland and the Old Swiss Confederation collapsed. On 12 April 1798, 121 cantonal deputies proclaimed the Helvetic Republic, "One and Indivisible". On 14 April 1798, a cantonal assembly was called in the canton of Zürich, but most of the politicians from the previous assembly were re-elected. The new régime abolished cantonal sovereignty and feudal rights. The occupying forces established a centralised state based on the ideas of the French Revolution.

Many Swiss citizens resisted these "progressive" ideas, particularly in the central areas of the country. Some of the more controversial aspects of the new regime limited freedom of worship, which outraged many of the more devout citizens.

In response, the Cantons of Uri, Schwyz and Nidwalden raised an army of about 10,000 men led by Alois von Reding to fight the French. This army was deployed along the defensive line from Napf to Rapperswil. Reding besieged French-controlled Lucerne and marched across the Brünig pass into the Berner Oberland to support the armies of Bern. At the same time, the French General Balthasar Alexis Henri Antoine of Schauenburg marched out of occupied Zürich to attack Zug, Lucerne and the Sattel pass. Even though Reding's army won victories at Rothenthurm and Morgarten, Schauenburg's victory near Sattel allowed him to threaten the town of Schwyz. On 4 May 1798, the town council of Schwyz surrendered.[8]

On 13 May, Reding and Schauenburg agreed to a cease-fire, the terms of which included the rebel cantons merging into a single one, thus limiting their effectiveness in the central government. However, the French failed to keep their promises in respecting religious matters and before the year was out there was another uprising in Nidwalden which the authorities crushed, with towns and villages burnt down by French troops.

No general agreement existed about the future of the Swiss. Leading groups split into the Unitaires, who wanted a united republic, and the Federalists, who represented the old aristocracy and demanded a return to cantonal sovereignty. Coup attempts became frequent and the new régime had to rely on the French to survive. Furthermore, the occupying forces insisted that the accommodation and feeding of the soldiers be paid for by the local populace, which drained the economy. The treaty of alliance of 19 August with France, which also reaffirmed the French annexation of the Prince-Bishopric of Basel and imposed French rights over the Upper Rhine and the Simplon Pass for evident strategic reasons towards Germany and Italy, also broke the tradition of neutrality established by the Confederation. All this made it difficult to establish a new working state.

In 1799, Switzerland became a virtual battle-zone between the French, Austrian, and Imperial Russian armies, with the locals supporting mainly the latter two, rejecting calls to fight with the French armies in the name of the Helvetic Republic.

Instability in the Republic reached its peak in 1802–1803; it included the Bourla-papey uprising and the Stecklikrieg civil war of 1802. By then, the Republic was 12 million francs in debt, having started with a treasury of 6 million francs.[9] This, together with local resistance, caused the Helvetic Republic to collapse, and its government took refuge in Lausanne.

At that time, Napoleon Bonaparte, then First Consul of France, summoned representatives of both sides to Paris in order to negotiate a solution. Although the Federalist representatives formed a minority at the conciliation conference, known as the "Helvetic Consulta", Bonaparte characterised Switzerland as federal "by nature" and considered it unwise to force the country into any other constitutional framework.

On 19 February 1803, the Act of Mediation abolished the Helvetic Republic and restored the cantons. With the abolition of the centralized state, Switzerland became a confederation once again, called the Swiss Confederation.

Constitution

[edit]Before the advent of the Helvetic Republic, each individual canton had exercised complete sovereignty over its own territory or territories. Little central authority had existed, with matters concerning the country as a whole confined mainly to meetings of leading representatives from the cantons: the Diets.[10]

The constitution of the Helvetic Republic came mainly from the design of Peter Ochs, a magistrate from Basel. It established a central two-chamber legislature which included the Grand Council (with 8 members per canton) and the Senate (4 members per canton). The executive, known as the Directory, comprised 5 members. The Constitution also established actual Swiss citizenship, as opposed to just citizenship of one's canton of birth.[10] Under the Old Swiss Confederacy, citizenship was granted by each town and village only to residents. These citizens enjoyed access to community property and in some cases additional protection under the law. Additionally, the urban towns and the rural villages had differing rights and laws. The creation of a uniform Swiss citizenship, which applied equally for citizens of the old towns and their tenants and servants, led to conflict. The wealthier villagers and urban citizens held rights to forests, common land and other municipal property which they did not want to share with the "new citizens", who were generally poor. The compromise solution, which was written into the municipal laws of the Helvetic Republic, is still valid today. Two politically separate but often geographically similar organizations were created. The first, the so-called municipality, was a political community formed by-election and its voting body consists of all resident citizens. However, the community land and property remained with the former local citizens who were gathered together into the Bürgergemeinde.[11]

After an uprising led by Alois von Reding in 1798, some cantons were merged, thus reducing their anti-centralist effectiveness in the legislature. Uri, Schwyz, Zug and Unterwalden together became the canton of Waldstätten; Glarus and the Sarganserland became the canton of Linth, and Appenzell and St. Gallen combined as the canton of Säntis.

Due to the instability of the situation, the Helvetic Republic had over 6 constitutions in a period of four years.[10]

Legacy

[edit]

The Helvetic Republic did highlight the desirability of a central authority to handle matters for the country as a whole (as opposed to the individual cantons which handled matters at the local level). In the post-Napoleonic era, the differences between the cantons (varying currencies and systems of weights and measurements) and the perceived need for better co-ordination between them came to a head and culminated in the Swiss Federal Constitution of 1848. The Republic's 5-member Directory resembles the 7-member Swiss Federal Council, Switzerland's present-day[update] executive.

The Helvetic Republic is still very controversial within Switzerland.[12] Carl Hilty described the period as the first democratic experience in Swiss territory, while within conservatism it is seen as a time of national weakness and loss of independence. For cantons such as Vaud, Thurgau and Ticino, the three who in 1898 celebrated the centenary of their independence, the Republic was a time of political freedom and liberation from the rule of other cantons. However, the period was also marked by foreign domination and instability, and for the cantons of Bern, Schwyz and Nidwalden it signified military defeat.[12] In 1995, the Federal Assembly chose not to celebrate the 200 year anniversary of the Helvetic Republic but to allow individual cantons to celebrate if they wished. The Federal Councilors took part in official events in Aargau in January 1998.[12]

The Helvetic period represents a key step toward the modern federal state. For the first time, the population was defined as Swiss, not as inhabitants of a specific canton.

Administrative divisions

[edit]

The Helvetic Republic reduced the formerly sovereign cantons to mere administrative division, though keeping the denomination of cantons, while also raising to such status unrepresented territories previously ruled as subjects of the Confederation. In order to weaken the old power-structures, it defined new boundaries for some cantons. The Act of 1798 and subsequent developments resulted in the following cantons:

Predecessor states

[edit]As well as the Old Swiss Confederacy, the following territories became part of the Helvetic Republic:

Associate states

[edit]There were four associated states:

Condominiums

[edit]There were 21 condominiums:

County of Baden

County of Baden Vogtei of Bellinzona

Vogtei of Bellinzona Vogtei of Blenio

Vogtei of Blenio Freie Ämter

Freie Ämter Vogtei of Gams / Hohensax

Vogtei of Gams / Hohensax Lordship of Grandson

Lordship of Grandson Vogtei of Leventina

Vogtei of Leventina Landvogtei of Locarno

Landvogtei of Locarno Landvogtei of Lugano

Landvogtei of Lugano Landvogtei of Mendrisio

Landvogtei of Mendrisio Vogtei of Murten

Vogtei of Murten

Vogtei of Orbe-Échallens

Vogtei of Orbe-Échallens Imperial Abbey of Pfäfers

Imperial Abbey of Pfäfers Vogtei of Rheintal

Vogtei of Rheintal Vogtei of Rivera

Vogtei of Rivera County of Sargans

County of Sargans Schwarzenburg / Grasburg

Schwarzenburg / Grasburg Landgraviate of Thurgau

Landgraviate of Thurgau County of Uznach

County of Uznach Landvogtei of Valmaggia

Landvogtei of Valmaggia Vogtei of Windegg

Vogtei of Windegg

Protectorates

[edit]There were five protectorates:

Unassociated territories

[edit]The Helvetic Republic also annexed two territories not previously part of Switzerland:

Fricktal, a part of the Breisgau, within the Habsburg Further Austria, retained by Aargau

Fricktal, a part of the Breisgau, within the Habsburg Further Austria, retained by Aargau Konstanz, a part of the Bishopric of Constance, later restored to the Grand Duchy of Baden

Konstanz, a part of the Bishopric of Constance, later restored to the Grand Duchy of Baden

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Helvetic Republic in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ The constitution of the Helvetic Republic Archived 8 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine, as described in the Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ Ayres-Bennett, Wendy; Carruthers, Janice (2018). Manual of Romance Sociolinguistics. De Gruyter. p. 529. ISBN 9783110365955. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Lerner, Marc H. (2023), "Switzerland: Local Agency and French Intervention: The Helvetic Republic", The Cambridge History of the Age of Atlantic Revolutions, vol. 2, Cambridge University Press, pp. 303–328, doi:10.1017/9781108599405.015, ISBN 978-1-108-47598-3

- ^ Marc H. Lerner, "The Helvetic Republic: An Ambivalent Reception of French Revolutionary Liberty," French History (2004) 18#1 pp 50–75.

- ^ R.R. Palmer, The Age of the Democratic Revolution 2:394-421

- ^ Otto Dann; John Dinwiddy (1988). Nationalism in the Age of the French Revolution. Continuum. pp. 190–98. ISBN 9780907628972. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ The French Invasion in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ Hughes, Christopher, Switzerland (London, 1975) p.98

- ^ a b c Histoire de la Suisse, Éditions Fragnière, Fribourg, Switzerland

- ^ Bürgergemeinde in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ a b c Helvetic Republic, Historiography and commemorations in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

External links

[edit]- Marabello, Thomas Quinn (2023) "Challenges to Swiss Democracy: Neutrality, Napoleon, & Nationalism," Swiss American Historical Society Review, Vol. 59: No. 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol59/iss2/5. Pg. 46-48.

- Helvetic Republic in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Divisions of Switzerland under Napoleon (in French)

- Helvetic Republic

- Client states of the Napoleonic Wars

- Former republics

- 1790s in Europe

- 1800s in Switzerland

- States and territories established in 1798

- States and territories disestablished in 1803

- 1798 establishments in France

- 1803 disestablishments in France

- 18th-century establishments in Switzerland

- 1803 disestablishments in Switzerland

- Former countries