Imperial Bedroom

| Imperial Bedroom | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 2 July 1982 | |||

| Recorded | November 1981 – March 1982 | |||

| Studio | AIR (London) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 50:49 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer | Geoff Emerick "from an original idea by Elvis Costello" | |||

| Elvis Costello and the Attractions chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Imperial Bedroom | ||||

| ||||

Imperial Bedroom is the seventh studio album by the English singer-songwriter Elvis Costello, and his sixth with the Attractions—keyboardist Steve Nieve, bassist Bruce Thomas and drummer Pete Thomas (no relation). It was released on 2 July 1982 through F-Beat Records in the United Kingdom and Columbia Records in the United States. Recording took place at AIR Studios in London from late 1981 to early 1982 with production handled by Geoff Emerick. Placing an emphasis on studio experimentation, the album saw the group use unusual instruments, including harpsichord, accordion and strings arranged by Nieve. Songs were rewritten constantly while Costello tinkered with the recordings, adding numerous overdubs.

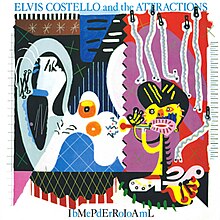

Employing a variety of pop styles that embody new wave, baroque pop and art rock, Imperial Bedroom contains an ornately lush production that several commentators compared to the Beatles and Phil Spector's wall of sound. The lyrics primarily concern love and relationships, with insight into the emotional problems of individuals. Squeeze's Chris Difford co-wrote the lyrics for "Boy With a Problem". The cover artwork, a painting by Barney Bubbles, is a pastiche of Pablo Picasso's Three Musicians.

Promoted under the tagline "Masterpiece?", Imperial Bedroom reached number 6 in the UK and number 30 in the US. Its singles, "You Little Fool" and "Man Out of Time", failed to break the top 50 in the UK. Its commercial performance led Costello to take a new direction with 1983's Punch the Clock. It was greeted with massive acclaim from music critics and continues to be regarded as one of Costello's best works. Reviewers praised the songwriting, production, instrumentation and performances, although its complexity was divisive. Imperial Bedroom has appeared on several best-of lists and has been reissued multiple times with bonus tracks.

Background

[edit]By 1981, Elvis Costello had released six studio albums in four years. Following the release of his country covers album Almost Blue (1981), the artist was facing diminishing popularity, particularly in America, where Trust (1981) and the Taking Liberties (1980) collection of outtakes had only reached the top 30;[1] Armed Forces (1979) and Get Happy!! (1980) both reached number two.[2] He had experimented musically with Get Happy!!, Trust and Almost Blue, and began to write more introspective lyrics than the angry material of his first three albums. However, the weaker commercial performances of these projects caused him to re-evaluate himself as an artist, leading him to take a new direction for his next album.[3]

Costello's initial vision for his seventh studio project was to record most of it live with minimal overdubs.[4][5] He and his backing band the Attractions—keyboardist Steve Nieve, bassist Bruce Thomas and drummer Pete Thomas (no relation)—spent two weeks rehearsing the material at a remote college in Devon using this method, yielding an eight-track album.[a] Costello eventually settled on using heavy studio experimentation when he found the material sounded too similar to Trust.[3][4]

Recording and production

[edit]

The band regrouped at London's AIR Studios in November 1981, where Costello had booked 12 weeks to record the album. He chose former Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick to produce the album, who the artist primarily used to "make his scattershot ideas a reality";[4] Emerick would be listed on the album sleeve as producing "from an original idea by Elvis Costello, assisted by Jon Jacobs".[6][7][8] It was Costello's first album of original material not produced by Nick Lowe, as Costello believed his complex ideas for the record would be too much for the producer;[3][6] engineer Roger Béchirian did not return either.[4] Lowe later returned to produce 1986's Blood & Chocolate.[6]

Emerick's primary role was to let the musicians take charge of themselves, as a way to "draw things out of the artist".[4] Costello commented in 1995: "He was used to being thrown an incomprehensible garble of sounds and musical directions and making some sense of it. After working with the Beatles at the height of their psychedelic era, he was used to innovation."[9] According to the author Tony Clayton-Lea, Emerick transformed the record from a "decent" eight-track demo album into an "aural tour de force".[3] The album was recorded at the same time as Paul McCartney's Tug of War,[3] on which Emerick simultaneously served as engineer while George Martin produced;[6] Emerick departed for small periods to work on Tug of War—with Jacobs taking over—before resuming work with Costello.[8] The artist later explained that he and McCartney were initially set to have non-conflicting recording schedules but the latter's was moved up, forcing Emerick to work between the two.[6]

The new record was Costello's first where the songs were not performed live before properly recording.[3] Costello instead drew upon brand new songs, but took some tracks from prior ventures: "Boy With a Problem" originated during the sessions for Trust, "Kid About It" from the artist's time producing Squeeze's East Side Story (1981) and "Tears Before Bedtime" during the sessions for Almost Blue. Tracks he wrote at home on the piano included "Almost Blue", "...And in Every Home" and "The Long Honeymoon".[6] Costello asked Sammy Cahn for input in writing what would become "The Long Honeymoon" but the writer declined, which gave him the motivation to finish writing it himself,[5] while Squeeze's Chris Difford co-wrote lyrics for "Boy With a Problem".[10]

To some extent Imperial Bedroom was the record on which the Attractions and I granted ourselves the sort of scope that we imagined the Beatles had enjoyed in the mid-'60s. We had engaged the engineering skills of the sonic, and somewhat unsung, genius behind many of those productions.[5]

—Elvis Costello, 2002

With an emphasis on studio experimentation, songs were constantly being rewritten in the studio; Costello took full control of the environment and concentrated the most on the sound of the recordings.[4][3] Unlike previous albums, where there was a general production idea, Costello stated that the band treated each song individually. Emerick concurred, stating, "My co-production consisted of abandoning the arrangements that we had carefully worked out."[11] Bruce Thomas recalled:[4][3]

The thing about Imperial Bedroom was that we went away and rehearsed all the songs and then didn't do the arrangements when we got in the studio. We just improvised totally new versions, changed the lyrics, changed the melody, changed the arrangement, so it's like we learned the structure of the songs then just deconstructed them and played completely different versions. [They] were changing all the time.

The group utilised unusual instruments, including mellotron, harpsichord, accordion, twelve-string guitar, marimba, strings and trumpets. Once Costello was satisfied with where a track was at, Emerick used his experience to shape them.[4][6][12] However, the "idiosyncratic, piecemeal approach" led to each track being led by a specific instrument rather than displaying the Attractions as a creative unit: "Shabby Doll" showcased piano and bass, while "Beyond Belief" showcased drums,[4] which Pete Thomas performed in one take after a heavy night of drinking;[11] Costello stated that Pete's performance led him to rewrite the number using the backing track as a guide.[5] A contemporary review from NME's Richard Cook noted that the guitars were demoted to "mere colouration", with the keyboards drawing "the predominant melodic shape".[10] Nieve also played the distorted guitar during the fade of "Tears Before Bedtime" as "a joke".[1]

The Attractions recorded some tracks without Costello present, such as "Pidgin English" and "Boy With a Problem".[4][6] Nieve arranged the majority of the string sections, including three Wagnerian-like French horns for "The Long Honeymoon", brass and woodwinds for "Pidgin English", "Philly-style violin" for "Town Cryer" and a full 40-piece orchestra for "...And in Every Home". Nieve conducted the orchestra himself, while Martin supervised the arrangement as it contained several allusions to his work with the Beatles;[6][11] Ringo Starr visited the studio during the session.[5]

The album's original working title was Music to Stop Clocks before being changed to This Is a Revolution of the Mind, a line from James Brown's "King Heroin" (1972). Clayton-Lea found this title "would blatantly publicize the health-conscious change of attitude".[3] It was changed again to P.S. I Love You—a line from "The Loved Ones" and "Pidgin English"[1]—before settling on Imperial Bedroom, the name of a track Costello wrote and recorded after the sessions wrapped.[5] He later remarked that the chosen title had "just the right combination of splendour and sleaze to fit all the tracks on the album".[1]

Later work

[edit]After completing the basic tracks in November 1981, Costello and the Attractions debuted several Imperial Bedroom tracks live during shows throughout late-December.[4] Reviewing the newer numbers during the New Year's Eve show, Robert Palmer of The New York Times commented: "Some of them have the harmonic and melodic sophistication of pop standards from the 1930s and 1940s."[13] On 7 January 1982, the band performed with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra at the Royal Albert Hall in London, mostly playing older hits and songs from Almost Blue and Imperial Bedroom.[4]

Costello continued tinkering with the Imperial Bedroom recordings alone throughout early 1982, including experimenting with vocal inflections on "Kid About It", "Human Hands" and "Pidgin English".[5] He also overdubbed "vocal groups" onto "Tears Before Bedtime", "The Loved Ones" and "Town Cryer" as a way to contrast with the more straightforward approaches in "Almost Blue", "Man Out of Time" and "The Long Honeymoon".[6] The biographer Graeme Thomson states that he wanted to move away from "having one feel throughout", a trait that had permeated Almost Blue.[4] He also commented that he believed the vocal and instrumental additions set Imperial Bedroom apart from his prior works.[6] The album was completed by March.[4]

Music and lyrics

[edit][The songs] exhibit a malaise of the spirit and a sinking feeling about happy endings. The souring and spoiling of England was just under way. Passing from town to town on the tours of the early '80s, I came to know some people who seemed just as disenchanted and discouraged. Their stories found their way into these songs.[5]

—Elvis Costello, 2002

A departure from the artist's previous albums,[14] Imperial Bedroom employs a variety of musical styles, characterised by commentators as new wave,[15][16] baroque pop,[17][18][19] and art rock.[12][20] Reviewers also found it Beatlesque,[18][21] and drew comparisons to Tin Pan Alley.[22][23][24] AllMusic's senior editor Stephen Thomas Erlewine regarded the songs as an extension of the jazz and pop infatuations explored on Trust.[24] In The New York Times, Palmer summarised, "the music is a sumptuous mélange of pop styles, from Beatles-baroque to Phil Spector Wall-of-Sound to torch-song intimacy."[25] Rolling Stone's Parke Puterbaugh wrote that the album contains a "potent, articulate musical kick" that relates to the Who's Tommy (1969), the Pretty Things' S.F. Sorrow (1968) and the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967).[26] The biographer David Gouldstone says the production makes the songs sound "spontaneous and immediate",[7] while the author James E. Perone remarks that Costello's voice is higher in the mix, presenting a "clearer presentation" of his voice than any of Lowe's productions.[12]

The lyrics on Imperial Bedroom are also a departure from previous albums, wherein every song is primarily concerned with topics of love and relationships, and delve further into the psych of dealing with emotions rather than the "revenge and guilt" fantasies of Costello's early work.[12][7][17][27] Gouldstone summarises the album as being about "the emotions, and more specifically the emotional problems, of individuals",[7] while Perone wrote that the songs "can be fully appreciated as a statement on importance of breaking through the noise and static of life to reach simple clarity and focus".[12] Puterbaugh compared its "thematic concerns" to the country albums Red Headed Stranger (1975) by Willie Nelson and The Battle (1976) by George Jones.[26] Many of the songs, particularly "Beyond Belief" and "Man Out of Time", represent an embellishment of somber reflection for Costello, having experienced numerous public and personal disturbances over the past five years and having little time for rumination.[5] Gouldstone states that every song on Imperial Bedroom is personal, with somewhat public themes on "Man Out of Time" and "Pidgin English" given personal embodiments.[7] Speaking to Palmer in June 1982, Costello commented that "the more personal songs are either imaginary scenarios, observations of other people, or observations of myself".[28] The subjects in the songs are far-reaching, representing a wide range of individuals from all levels of society.[27] After having mostly third person narrators on Trust,[29] Imperial Bedroom utilises mostly first-person narrators, with third-person ones making appearances on "The Long Honeymoon", "...And in Every Home" and "You Little Fool".[7] Despite some of the lyrical content, Costello imagined this to be his most optimistic album to date.[6]

Side one

[edit]The opening track, "Beyond Belief", evokes 1960s psychedelia and utilises an unusual song structure, wherein there is melodic contrast from section-to-section and the chorus does not appear until the track's outro, to describe a tense relationship study between two mutually mismatched forces.[12][10][30][31] Providing commentary on the confused state of the world, the song sets up a recurring theme where people do not learn from their mistakes.[7][12] Gouldstone comments that while Costello had previous acted as an observer or outsider, with "Beyond Belief" he now acts in a more positive role than playing a cynical observer.[7] AllMusic's Bill Janovitz viewed the track's use of vocal layering, effects and instrumentation as resembling and predating techniques of sampling and looping before their widespread use in rock.[31] "Tears Before Bedtime" returns to the "marital claustrophobia" of numerous Get Happy!! tracks,[7] concerning a dysfunctional relationship where the characters have given up hope that the fighting will end. Perone finds the song evidence of Costello's continued development in aligning moods of the words and music.[12]

"Shabby Doll" is an exploration of the feelings of anger and hate that come with rejection.[12] Taking its title from an old cabaret poster Costello saw in a hotel dining room,[b][5][33] the male character describes his female lover as a "shabby doll"—meaning she was once glamorous but is now past her prime—but by the end of the song, the role have reversed and he becomes the "shabby doll".[12][7] Like other album tracks, the song displays the artist's acknowledgement of distributing blame evenly between men and women that began on Trust. Its themes of betrayal are aided by the tension-building instrumentation of the Attractions.[12][33] "The Long Honeymoon" is a tale of infidelity that employs a Latin-type groove, jazz and lounge inflections on piano and French cabaret-style accordion.[7][12][34] Perone likens its arrangement to a 1940s/1950s torch song.[12] Its instrumental middle section boasts a rare guitar solo from Costello. Gouldstone compares its themes to the Trust numbers "Big Sister's Clothes" and "Shot With His Own Gun".[7]

Costello felt the partly autobiographical "Man Out of Time" was the "heart" of the album.[5][8] Bookended by a fast-paced band-led performance with screaming[12]—the initial recorded version[4]—"Man Out of Time" boasts a wall of sound production and excessive wordplay to describe three characters: the narrator, a woman and a man who holds a public position. The details are minimal and obtuse, but Gouldstone interprets it as the narrator's plea for the woman to love him after the man has left her; if she does not love him, he loses grasp on reality.[7][30] AllMusic's Rick Anderson opined that the song presents both the "best" and "worst" of the album, but found its "lush and heartbreakingly pretty" production lends the chorus its emotional weight.[22]

"Almost Blue"—titled after his preceding album of country covers—was based on Chet Baker's recording of "The Thrill Is Gone".[4] The album's only track that is not heavily produced,[7] "Almost Blue" is played in a somber jazz and lounge style, emphasising changing harmonies.[12] In "Almost Blue", the main character is devoid of feeling as he is lost in love, which he brought upon himself, while being in a relationship that has never reached full happiness.[7][12] Janovitz associated its sorrow quality to Frank Sinatra's 1954 In the Wee Small Hours and 1958 Only the Lonely LPs and overall mood to Miles Davis's Kind of Blue (1959).[35] In contrast to "Almost Blue", "...And in Every Home" vaunts the most extravagant production on the album. Its music is led by Nieve's orchestral arrangements,[12][20] which one reviewer likened to the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper.[34] The lyrics depict stagnant views of relationships, whose individuals' act in age-inappropriate ways; the characters cheat on their spouses with individuals half their age in an attempt to recapture their youth.[12][20] Gouldstone interprets it as a study of the waste of lives and marriage destruction.[7]

Side two

[edit]Costello described "The Loved Ones" as "the horror of a parade of relations at the fate of a doomed and wasted youth".[32] A mid-1960s pop number, Perone found its impressionist imagery catches a despised man in the midst of being alienated from society.[12] "Human Hands" is an operatic love song about the desire for human contact, with images of masturbation and prostitution.[12] According to Gouldstone, the narrator's seclusion is accentuated through references to the hostility of the outside world. Like "Man Out of Time", "he needs love to protect him from the chaos surrounding him", although his repeated attempts result in failure.[7]

Costello wrote "Kid About It" the morning after John Lennon's murder and reflects his mindset following the event.[5] A gospel-inspired waltz with a simple arrangement,[8][12] AllMusic's Stewart Mason compared the track's "1950s cool jazz" sound with that of "Almost Blue".[36] In "Kid About It", the narrator pleads to his lover but believes she is behaving immaturely and not taking the relationship seriously. Wanting to return to a less complicated time, he is done playing games and wants to fully settle down.[7][12] For his vocals, Costello sang in his lowest octave and strained on some of the higher notes, which Mason felt added "vulnerability" to the "emotionally open lyrics".[5][36] "Little Savage" returns to a more conventional pop/rock song style and structure.[c][12] The music contrasts with the lyrical theme of the difficulties and failures of relationships,[7] wherein the main character tells his lover his drinking eases the "emotional baggage" of their relationship.[12]

"Boy With a Problem" mixes midcentury torch with contemporary rock and connects prominent lyrical ideals throughout the record, including alcoholism, domestic violence, impotence, relationship dysfunction and lack of self-esteem.[12] The song depicts a marriage going through a tough period, in which the husband is drinking again and both parties are committing acts of violence on one another. The ending gives a sense of hope that she will forgive him.[7] In a stylistic detour, "Pidgin English" echoes 1960s psychedelia to a major extent.[12][37] Mason observes that the vocals are double-tracked in both stereo channels, giving the appearance of dueling inner dialogues.[37] In an example of Imperial Bedroom's focus on breaking free from the static of daily life, the song offers an expansion on the themes of "Human Hands", with Perone stating that it displays "numerous images of people's inability to articulate their emotions in a stream-of-consciousness style and contrasts the resulting confusion with the oft-repeated fade-out phrase "P.S. I love you".[12] Costello elaborates that "among the colloquialisms and lyrical puzzles of 'Pidgin English', there is a longing for the simple words to express love".[5]

"You Little Fool" is a more straightforward number akin to mid-1960s pop equipped with a harpsichord;[7][12][38] the author Mick St. Michael viewed it as "one step" from the Rolling Stones' "Mother's Little Helper" (1966).[1] In a lyric mirroring Trust's "Big Sister's Clothes", a teenage girl is ready to grow up to adulthood while her parents do not understand her nor approve of her love life. Perone says "You Little Fool" offers a culmination of the album's themes of "dejection over the messes people make of their lives".[7][12] The final track, "Town Cryer", is a soft soul ballad that uses Nieve's orchestral arrangements to the fullest extent; by the song's extended coda, the orchestra overtakes the rest of the band.[12][39] Costello utilises heavy wordplay to portray a man who has lost at love and has reached his breaking point: he dubs himself a "town crier" and is anxious to make his tears public. Gouldstone argues the introspective tone comes off as a deliberate personal confession.[7][12] Reviewing Imperial Bedroom on release, Trouser Press's Scott Isler argued that the line, "love and unhappiness go arm in arm", perfectly describes the album thematically.[17] Gouldstone contends that if the album itself is a quest to improve satisfaction following the overall dissatisfaction of Costello's earlier albums, the LP ends relatively the same as how it started; however, he maintains the journey itself has been "an enriching experience", and the long fade out of "Town Cryer" allows the listener to process the album as a whole before it ends.[7]

Artwork and packaging

[edit]

The cover artwork, a painting titled Snakecharmer & Reclining Octopus by Barney Bubbles (credited to "Sal Forlenza"), is a pastiche of Pablo Picasso's Three Musicians (1921). Costello was taken aback upon seeing the painting for the first time, believing Bubbles had responded to "the more violent and carnal aspects of the songs".[d][11][32] The painting depicts a resting woman with laced hands surrounded by zipper-like creatures—which spell out "Pablo Si"—sitting next to ringmaster-type figure, wearing what Costello interpreted as a tricorn hat.[32] In his book Let Them All Talk, Hinton describes the picture as "a violent exercise in harsh red and blues".[e][11] The cover won the Creem readers' poll for the best album cover of 1982.[40] The original LP's inner sleeve boasted photographs by David Bailey of the entire band in black-and-white.[11][41] The one of Costello, in which he glares into the camera with his chin resting on his fist, was used as the sleeve photo for the "Man Out of Time" single.[11]

Imperial Bedroom was Costello's first album to include a lyric sheet.[12] In a 1995 interview with the author Peter Doggett, he explained that up until that point, he was uncomfortable with having "little poems" printed on the sleeve, preferring his words to be heard rather than read.[9] Gouldstone interpreted the inclusion as to possibly not be misheard or misinterpreted.[7] The lyrics appear in a continuous flow, without punctuation nor breaks between songs, and in all caps,[17][10] which was done by Bubbles at Costello's instruction as he wanted the final result to be a graphic effect rather than, in his words, "stressing any order or hierarchy on the page".[f][32] Speaking to Doggett, he said: "It makes for quite interesting reading. You can make up your own lines, starting in the middle of one song and into the next one."[9] Eric Klinger of PopMatters later argued that the sheet "lent to the air of mystery and challenge to the listening", making it "even more of an immersive experience".[42]

Release and promotion

[edit]Although the album was finished by March 1982, its release was pushed back four months due to financial disputes between F-Beat and Columbia Records. Costello and the Attractions toured Holland and Oceania from April to June as pre-release promotion.[4] Released on 2 July 1982,[8][24] Imperial Bedroom reached number 6 on the UK Albums Chart and number 30 on the US Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart;[43][44] it spent 12 weeks overall in the UK top 100.[1] Elsewhere, it peaked at number 18 in Norway,[45] 30 in Sweden,[46] 37 in New Zealand,[47] 45 in the Netherlands and 49 in Australia.[48][49] F-Beat also issued a now-rare collectible double promotional LP, titled A Conversation with Elvis Costello, featuring album tracks interspersed with comments by the artist on the makings of each track.[1][9][11]

The album's singles performed poorly. The first, "You Little Fool" backed by the Lowe-produced outtakes "Big Sister" and "The Stamping Ground", was released in June 1982 and reached number 52 in the UK.[50][51] The second, "Man Out of Time" backed by an alternate version of "Town Cryer", was released in late-July and reached number 58; both failed to chart in the US.[50][51] The label, expecting another success akin to Armed Forces, were disappointed with the performance of Imperial Bedroom.[11][3] Costello later opined that the label's choices of singles were poor and "did little" to designate the album's change of style from previous records; he felt "Beyond Belief" would have performed well as the first single.[5][9] The non-album single "From Head to Toe", a Smokey Robinson cover, was issued in September and performed better than both Imperial Bedroom singles.[4][5] Clayton-Lea opines that Costello was "swimming against the commercial tide" in the age of New Romantic bands such as Adam and the Ants, Duran Duran, Depeche Mode, the Human League and Soft Cell.[3]

Imperial Bedroom was promoted under the one-word tagline, "Masterpiece?", which Thomson says attracted as much positive publicity as it did negative.[4] After refusing to conduct interviews for several years, Costello began speaking with the press again, explaining: "In the beginning [of my career], I did a few interviews, and I didn't feel they went very well, so I just stopped doing them. [...] Then when the time went by, and I felt there were some thing that were perhaps necessary to explain, I changed my mind."[4] According to Thomson, Costello's initial refusal did little to help in his diminishing sales numbers, as interviews were essential to album promoting at the time.[4] During a particular interview with Rolling Stone's Greil Marcus, he atoned for an incident that occurred on the American Armed Funk Tour in March 1979, in which he insulting various American musical artists James Brown and Ray Charles, using racial slurs, in a drunken exchange with Stephen Stills.[52] He gave further apologetic comments in The New York Times, Newsweek and the Los Angeles Times.[g][4][3]

Critical reception

[edit]| Initial reviews | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Record Mirror | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Smash Hits | 9/10[55] |

| Sounds | |

| The Village Voice | B+[57] |

Upon release, Imperial Bedroom was greeted with near universal acclaim.[4] Drawing comparisons to Sgt. Pepper,[58] Puterbaugh declared in Rolling Stone that Costello had written his masterpiece following years of experimentation.[26] Sounds magazine's Dave McCullough arguing that it sees Costello reach a "kind of peak of peaks".[56] In a highly positive review for NME, Richard Cook proclaimed: "This is pop music organised to an incredible sophistication. However it has been achieved, ... it sets out parameters of sound that seem to alter within the inner ear: which means that Costello has finally achieved a synthesis of words and music that correlates to the duplicity of each."[10]

Critics expressed admiration for Costello as a songwriter and artist.[h] Several declared him the finest songwriter in pop music,[14][59][58] earning comparisons to Lennon and McCartney, Cole Porter and George Gershwin.[31][38][60] Smash Hits writer David Hepworth asserted: "Like steel going through butter, the songs are offset by an edge that only a craftsman could manufacture."[55] Some critics felt Imperial Bedroom pushed Costello to the forefront of musical innovation, despite lacking major commercial appeal.[i] Record Review's David M. Gotz argued that the artist lacked youth appeal, but his work nonetheless "continues to be a stimulating experience for those who have enough time and sense to listen. [...] But he is definitely writing and performing some of the best songs in pop music."[61] Isler argued in Trouser Press that the album's recognition would improve over time, similar to the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds (1966).[17]

Reviewers highlighted the music, lyrics, Nieve's piano and orchestral work, and Emerick's production,[j] although Billboard magazine questioned whether Costello's longtime fans would appreciate it compared to the more "rough-edged rock" of Costello's Lowe-produced records.[64] Several gave high praise to the Attractions,[38][61] although some noted the band played a lesser role in the arrangements compared to previous records.[34][14] Reactions to Costello's singing were mostly positive, labelled by some the strongest of his career.[54][58] Others acknowledged the change in attitude from the artist's previous albums,[15][64] Barry Alfonso of LA Weekly describing Imperial Bedroom as "the most benign album he's recorded yet, a far cry from the bulk of his material four years ago".[14]

Critics were, however, divided on Imperial Bedroom's complexity.[15][65] While some argued it made Imperial Bedroom an album that would enjoy repeated listens,[26][34][38] others felt its concentration on complexity resulted in a "pretentious" and non-"easy-listening" final product that softened the impact of the songs.[18][57] Costello's lyrical wordplay was viewed as too cumbersome by some, but praised for its vocabulary.[k] Ken Tucker of The Philadelphia Inquirer griped that "In song after song, Costello forces you to become nothing more than a picky English teacher, grading his self-conscious compositions."[16] More negatively, some believed the album was more "artifice than art" and lacked innovation.[16][67] Bill Carlton of the New York Daily News wrote that Costello lacked the voice to convey the lyrics in an emotional way, describing the album as "pompous, narrow-minded, pseudo-literary hooey mired in incoherent, desultory musical forms, boring, lifeless melodies and log-jammed lyrics".[68]

Imperial Bedroom made appearances on several lists of the year's best albums, including number one placements by Record Mirror and The Village Voice on its annual Pazz & Jop critics poll.[69][70] NME placed it number two, behind Marvin Gaye's Midnight Love; the publication also placed "Man Out of Time" as one of the year's top ten tracks.[71] Additionally, The New York Times ranked it 1982's seventh best album,[25] while Rolling Stone included it in their list of the year's top 40 albums, recognising the LP as Costello's "most fully realized" and "most compassionate" album to date.[72]

Tour and subsequent events

[edit]Costello and the Attractions toured America from July to September 1982.[4] The singer boasted more friendly on-stage demeanor compared to previous tours,[11] including a stunt where he appeared in a full gorilla suit during the encore of the show coinciding with his 28th birthday. The setlists embraced funk and R&B flavours and mostly consisted of material from Get Happy!!, Trust and Imperial Bedroom, as well as covers and old hits.[4] He received backlash from fans who only wanted to hear older hits, which challenged him; he had previously rejected fan requests. Additionally, the studio craft of Imperial Bedroom meant the tracks, particularly "...And in Every Home", "Beyond Belief" and "Man Out of Time", were harder to play live.[4]

[Imperial Bedroom] got some of the greatest reviews imaginable, [but] it didn't sell more than any other record. The record company couldn't find any obvious hit singles on it, though I thought it had several.[4]

—Elvis Costello

Despite the massive critical success of Imperial Bedroom, its modest commercial performance forced Costello to reevaluate his musical style. Columbia, remaining eager for another Armed Forces, showed little interest in the artist's less-commercial works.[4] By 1982, Costello had garnered a loyal fanbase, largely through his own merits, but knew his heavily artistic and challenging material was doing him more harm than good, so he decided to change direction with his next record. He and the Attractions briefly toured Britain from mid-September to early-October, road-testing several new songs that would appear on 1983's Punch the Clock.[3][4][24]

Retrospective appraisal

[edit]| Retrospective reviews | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| The Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Entertainment Weekly | A+[76] |

| Mojo | |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Uncut | |

In later decades, Imperial Bedroom has received acclaim as one of Costello's best records,[19][24][42][80] with some proclaiming it his masterpiece.[12][31][21] Commentators agreed the record was Costello's showcase as a songwriter,[35][81] standing as the Bob Dylan or Van Morrison of the new wave era,[31] and earning him the respect of musicians and critics who disregarded him as a punk rocker.[24] In his book Let Them All Talk, Hinton proclaims Imperial Bedroom as "an album of astonishing vitality and musical optimism" that "remains perhaps his most perfect achievement", occupying "an aural richness" that would return on 1996's All This Useless Beauty.[11] Reviewing Costello's entire career, Klinger argued that its musical styles predated the artist's collaborations with Burt Bacharach, Allen Toussaint and the Brodsky Quartet.[42] On its 40th anniversary, Allison Rapp of Ultimate Classic Rock stated that Imperial Bedroom was one of Costello's most mature attempts at wrestling with one's existentialism.[82]

The production has been praised for its intricacy, offering a listening experience that rewards repeated listens.[l] Others have argued the album has aged well and highlight its wordplay,[7][83][79] and the performances of the Attractions.[8][73] Mojo's Mat Snow gave particular praise to Bruce Thomas's basslines and compared them to that of Paul McCartney, calling his work "models of dramatic invention".[81] Bruce himself considered it Costello and the Attractions' best record: "We were all throwing in musical ideas."[11] In his book The Words and Music of Elvis Costello, Perone contends that the LP demonstrated that the band could thrive in a more musically expansive environment compared to previous albums.[12] Actor Robert Downey Jr. named Imperial Bedroom his favourite album of all time in 2005. Speaking to Uncut, he stated:[84]

My first impression of it was that I could imagine someone spending their entire life thinking an album like this out, having enough life experience, getting the musicianship right. There was just so much on it. So many words, so many ideas. And every song is a triumph. It took me about 10 years to even begin to understand it. [...] [Costello's] made so many great albums, but Imperial Bedroom is the one that says: 'This is where the bar has been – now how about this, you fuckers?'

Imperial Bedroom has not been without its detractors, particularly regarding the production. Writing for Blender magazine, Douglas Wolk stated that the "hyperdense songwriting" and elaborate orchestrations make for a difficult listening experience,[73] a sentiment echoed by Slant Magazine.[83] Others, including Treblezine's Tyler Parks, have found it "pretentious" and "obsessed with its own virtuosity",[30] while Jason Mendelsohn of PopMatters believed its lush set pieces were the record's greatest strength and weakness, becoming so "overwrought" it makes you yearn for the artist's simpler works.[42] Costello himself admitted in the 2002 liner notes that the record "is not exactly easy listening as it is".[5] Gouldstone argues that "whatever your opinion of the production, Imperial Bedroom remains a collection of high-quality songs".[7]

Rankings

[edit]Imperial Bedroom has made appearances on several best-of lists. In 1989, Rolling Stone ranked it number 38 on its list of the 100 greatest albums of the 1980s.[85] Over two decades later, Slant Magazine listed the album at number 59 in a similar 2012 list. Staff writer Huw Jones stated that the album "affirms Costello as a poet laureate for the counterculture and a restless musical genius all in the space of 50 topsy-turvy minutes".[83] Three years later, the album was also included by Ultimate Classic Rock in their list of the 100 best rock albums of the 1980s.[60] In 1998, readers of Q magazine named it the 96th greatest album ever.[86] Five years later in 2003, Rolling Stone placed Imperial Bedroom at number 166 on list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time,[87] maintaining the rating in a 2012 revised list.[88]

The album was also voted number 321 in the third edition of writer Colin Larkin's book All Time Top 1000 Albums (2000),[89] and included in the 2018 edition of Robert Dimery's book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[90]

Reissues

[edit]Imperial Bedroom was first released on CD through Columbia and Demon Records in January 1986.[91] Its first extended reissue through Demon in the UK and Rykodisc in the US on CD came in May 1994, which was packaged with a slew of bonus tracks, including various outtakes and tracks recorded during sessions as Matrix Studios in February 1982.[92][91] The additional material received a positive mention by David Cavanagh in Q.[21] Imperial Bedroom was again reissued by Rhino Records on 19 November 2002 as a two-disc set with additional bonus tracks, including material from the initial two-week rehearsals preceding the sessions.[93][5] The album was later remastered and reissued by UMe on 6 November 2015.[94]

Track listing

[edit]All songs written by Elvis Costello, except where noted.

Original album

[edit]Side one

- "Beyond Belief" – 2:34

- "Tears Before Bedtime" – 3:02

- "Shabby Doll" – 4:48

- "The Long Honeymoon" – 4:15

- "Man Out of Time" – 5:26

- "Almost Blue" – 2:50

- "...And in Every Home" – 3:23

Side two

- "The Loved Ones" – 2:48

- "Human Hands" – 2:43

- "Kid About It" – 2:45

- "Little Savage" – 2:37

- "Boy With a Problem" (lyrics: Costello, Chris Difford) – 2:12

- "Pidgin English" – 3:58

- "You Little Fool" – 3:11

- "Town Cryer" – 4:16

1994 bonus tracks

[edit]All tracks produced by Elvis Costello.

- "From Head to Toe" (Smokey Robinson) – 2:34

- "The World of Broken Hearts" (Mort Shuman, Doc Pomus) – 3:01

- "Night Time" (Patrick Chambers) – 2:52

- "Really Mystified" (Tony Crane, John Gustafson) – 2:03

- "I Turn Around" (Demo) – 2:09

- "Seconds of Pleasure" (Version 2 of "The Invisible Man") – 3:43

- "The Stamping Ground" (Demo) – 3:09

- "Shabby Doll" (Early version) – 4:18

- "Imperial Bedroom" (Demo) – 2:47

2002 bonus disc

[edit]- "The Land of Give and Take" (Early version of "Beyond Belief") – 3:05

- "Tears Before Bedtime" (Alternate version) – 3:03

- "Man Out of Time" (Alternate version) – 3:43

- "Human Hands" (Early version) – 2:44

- "Kid About It" (Alternate version) – 3:18

- "Little Savage" (Alternate version) – 3:07

- "You Little Fool" (Alternate version) – 2:59

- "Town Cryer" (Fast version) – 2:15

- "Little Goody Two Shoes" (Alternate version of "Inch by Inch") – 3:10

- "The Town Where Time Stood Still" (Alternate version) – 2:57

- "...And in Every Home" (Rehearsal) – 3:12

- "I Turn Around" – 2:09

- "From Head to Toe" (Robinson) – 2:34

- "The World of Broken Hearts" (Shuman, Pomus) – 3:01

- "Night Time" (Chambers) – 2:52

- "Really Mystified" (Crane, Gustafson) – 2:03

- "The Stamping Ground" – 3:09

- "Shabby Doll" (Demo version) – 4:18

- "Man Out of Time" (Demo version) – 3:27

- "You Little Fool" (Demo version) – 3:11

- "Town Cryer" (Demo version) – 3:03

- "Seconds of Pleasure" (Demo version) – 3:19

- "Imperial Bedroom" – 2:47

Personnel

[edit]Credits adapted from AllMusic:[95]

- Elvis Costello – vocals, guitar, piano

- Steve Nieve – piano, organ, orchestrations, harpsichord,[4] accordion,[12] guitar on "Tears Before Bedtime"[1]

- Bruce Thomas – bass

- Pete Thomas – drums

Production

- Geoff Emerick – producer

- Jon Jacobs – assistant producer[6]

- Daniel Hersch – mastering

- David P. Bailey – photography

- Barney Bubbles – cover design

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1982) | Peak Position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (Kent Music Report)[49] | 49 |

| Dutch Albums (MegaCharts)[48] | 45 |

| New Zealand Albums (RIANZ)[47] | 37 |

| Norwegian Albums (VG-lista)[45] | 18 |

| Swedish Albums (Sverigetopplistan)[46] | 30 |

| UK Albums Chart[43] | 6 |

| US Billboard Top LPs & Tape[44] | 30 |

Notes

[edit]- ^ All that survives from these rehearsals on the finished album is the screaming introduction and tag that bookends "Man Out of Time". Material from these sessions were later released on the 2002 Rhino reissue of the album.[5]

- ^ Costello recalled John Lennon using a carnival poster as the basis for the Beatles' "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!" (1967) and wanted to the same for one of his own compositions.[32]

- ^ In the 2002 reissue liner notes, Costello stated that the album's slower pace necessitated the more up-tempo arrangement of "Little Savage", but found the unfinished version packaged in the reissue better served the song's overall meaning.[5]

- ^ According to his 2015 memoir, Bubbles' original painting is still in Costello's possession.

- ^ Costello would make a similar painting himself for the cover of Blood & Chocolate.[32]

- ^ In his memoir, Costello states that he initially resisted calls to include a lyric sheet but eventually relented.

- ^ Reflecting on the incident in his 2015 memoir, Costello wrote: "So what if my career was rolled back off the launching pad? Life eventually became a lot more interesting due to this failure to get into some undeserved and potentially fatal orbit."[53]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[17][26][56][57][25]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[10][17][55][61]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[26][16][58][61][34][10][55][62][54][63]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[38][10][58][14][66][23][59]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[4][42][81][21][19][30]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h St. Michael 1986, pp. 82–89.

- ^ "Elvis Costello – full Official Chart History". officialcharts.com. Official Charts Company. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Clayton-Lea 1999, chap. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Thomson 2004, chap. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Costello, Elvis (2002). Imperial Bedroom (reissue) (CD liner notes). Elvis Costello and the Attractions. US: Rhino Records. R2 78188.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Costello, Elvis (1994). Imperial Bedroom (reissue) (CD liner notes). Elvis Costello and the Attractions. US: Rykodisc. RCD 20278.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Gouldstone 1989, chap. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f Leviton, Mark (2 July 2022). "Elvis Costello and the Attractions' 'Imperial Bedroom': Multi-Colored Delights". Best Classic Bands. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Doggett, Peter (September 1995). "Elvis Costello: The Record Collector Interview". Record Collector. No. 193. pp. 38–44.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cook, Richard (3 July 1982). "Costello's confessional". NME. p. 33. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hinton 1999, chap. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Perone 2015, pp. 52–60.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (2 January 1982). "Pop: Elvis Costello's Celebration". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Alfonso, Barry (13–19 August 1982). "Elvis Costello perfects his aim". LA Weekly. p. 23. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- ^ a b c Walls, Richard C. (November 1982). "E.C.'s Emotional Rescue". Creem. p. 56. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2022 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ a b c d Tucker, Ken (18 July 1982). "Elvis Costello's 'Imperial Bedroom' can't match passion of early albums". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 12I. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- ^ a b c d e f g Isler, Scott (October 1982). "Not so silly love songs". Trouser Press. No. 78. p. 33.

- ^ a b c Himes, Geoffrey (22 August 1982). "Retain the Rock, Revive the Refined". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Gallucci, Michael (15 February 2022). "Elvis Costello Albums Ranked Worst to Best". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Mason, Stewart. "'...And in Every Home' – Elvis Costello / Elvis Costello & the Attractions". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Cavanagh, David (November 1994). "Elvis Costello & the Attractions: Imperial Bedroom". Q. No. 98. p. 136.

- ^ a b Anderson, Rick. "'Man Out of Time' – Elvis Costello / Elvis Costello & the Attractions". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ a b McCollum, Charles (19 August 1982). "Acidic Elvis going soft". The Washington Times. p. 2C.

- ^ a b c d e f g Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Imperial Bedroom – Elvis Costello / Elvis Costello & the Attractions". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Palmer, Robert (22 December 1982). "The Pop Life". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Puterbaugh, Parker (5 August 1982). "Imperial Bedroom". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 15 November 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ a b Swenson, John (31 October 1982). "Imperial Bedroom: Elvis Costello". Circus. pp. 75–76.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (27 June 1982). "Elvis Costello – Is He Pop's Top?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Gouldstone 1989, chap. 6.

- ^ a b c d Parks, Tyler (6 September 2006). "Elvis Costello and the Attractions: Imperial Bedroom review". Treblezine. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Janovitz, Bill. "'Beyond Belief' – Elvis Costello / Elvis Costello & the Attractions". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Costello 2015, pp. 66–75.

- ^ a b Janovitz, Bill. "'Shabby Doll' – Elvis Costello / Elvis Costello & the Attractions". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Denselow, Robin (9 July 1982). "Imperial Bedroom: Elvis Costello and the Attractions". The Guardian. p. 8. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- ^ a b Janovitz, Bill. "'Almost Blue' – Elvis Costello / Elvis Costello & the Attractions". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ a b Mason, Stewart. "'Kid About It' – Elvis Costello / Elvis Costello & the Attractions". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ a b Mason, Stewart. "'Pidgin English' – Elvis Costello / Elvis Costello & the Attractions". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Griffin, John (23 July 1982). "Elvis Costello comes of age". Montreal Gazette. p. C-8.

- ^ Mason, Stewart. "'Town Cryer' – Elvis Costello / Elvis Costello & the Attractions". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ "1982 Readers' Poll". Creem. March 1983.

- ^ Parkyn 1984, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e Mendelsohn, Jason; Klinger, Eric (5 February 2016). "Counterbalance: Elvis Costello and the Attractions – Imperial Bedroom". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Imperial Bedroom by Elvis Costello & the Attractions". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 14 December 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Elvis Costello Chart History". Billboard. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Elvis Costello and the Attractions – Imperial Bedroom" (ASP). norwegiancharts.com. VG-lista. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Elvis Costello and the Attractions – Imperial Bedroom" (ASP). swedishcharts.com (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Elvis Costello and the Attractions – Imperial Bedroom" (ASP). charts.nz. Recording Industry Association of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Elvis Costello and the Attractions – Imperial Bedroom" (ASP). dutchcharts.nl (in Dutch). MegaCharts. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992. St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ a b Hinton 1999, p. 428.

- ^ a b Parkyn 1984, p. 31.

- ^ Marcus, Greil (2 September 1982). "Elvis Costello Explains Himself". Rolling Stone. No. 377. pp. 12–17. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ Costello 2015, pp. 336–339.

- ^ a b c Hills, Simon (3 July 1982). "The main attraction" (PDF). Record Mirror. p. 26. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2022 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ a b c d Hepworth, David (8–21 July 1982). "Imperial Bedroom: Elvis Costello". Smash Hits. 4 (14): 23.

- ^ a b c McCullough, Dave (10 July 1982). "Breathless in bed". Sounds. p. 10.

- ^ a b c Christgau, Robert (5 October 1982). "Christgau's Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Considine, J. D. (August 1982). "Imperial Bedroom: Elvis Costello & the Attractions". Musician. No. 46. p. 88. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ a b Miller, Jim (9 August 1982). "No More Mr. Bad Guy". Newsweek. p. 41.

- ^ a b "Top 100 '80s Rock Albums". Ultimate Classic Rock. 12 July 2015. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d Gotz, David M. (December 1982). "Elvis in a mellow mood". Record Review. p. 49.

- ^ "Reviews: Out of the Box" (PDF). Cash Box. 10 July 1982. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ Marsh, Dave (24 September 1982). "Elvis Costello makes a stab at an '80s Beatles album". The Charlotte Observer. p. 2D.

- ^ a b "Top Album Picks" (PDF). Billboard. 10 July 1982. p. 62. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ Miles, Milo (13 July 1982). "Costello Unbound: Elvis brings fire to pop". The Boston Phoenix. p. 56. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ Birch, Ian (August 1982). "Imperial Bedroom: Elvis Costello and the Attractions". The Face. No. 28. p. 38.

- ^ Sweeting, Adam (3 July 1982). "Man out of time". Melody Maker. p. 16.

- ^ Carlton, Bill (8 July 1982). "Costello: music to torture yourself by". New York Daily News. p. 65.

- ^ "Albums of the Year" (PDF). Record Mirror. 1 January 1983. p. 7. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ "The 1982 Pazz & Jop Critics Poll". The Village Voice. 22 February 1983. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ "Albums and Tracks of the Year". NME. 2016. Archived from the original on 28 October 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ "The Top Forty Albums". Rolling Stone. No. 385. 23 December 1982. p. 105.

- ^ a b c Wolk, Douglas (March 2005). "Elvis Costello: Imperial Bedroom". Blender. Archived from the original on 4 February 2005. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ Kot, Greg (2 June 1991). "The Sounds Of Elvis, From San Francisco And Beyond". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2011). "Costello, Elvis". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- ^ White, Armond (10 May 1991). "Elvis Costello's albums". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 21 October 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ Doyle, Tom (November 2018). "Band Substance". Mojo. No. 300. p. 59.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (2004). "Elvis Costello". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). London: Fireside Books. pp. 193–195. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8. Archived from the original on 13 December 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ a b Hasted, Nick (January 2003). "Snide effects". Uncut. No. 68. p. 138.

- ^ Shipley, Al (30 January 2022). "Every Elvis Costello Album, Ranked". Spin. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Snow, Mat (December 2002). "Elvis Costello re-releases". Mojo. No. 109.

- ^ Rapp, Allison (2 July 2022). "When Elvis Costello Looked Inward on 'Imperial Bedroom'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 17 July 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Jones, Huw (5 March 2012). "The 100 Best Albums of the 1980s". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Downey, Robert Jr. (September 2005). "Imperial Bedroom – Elvis Costello & the Attractions". Uncut. No. 100. p. 33.

- ^ "Top 100 Albums of the 80s". Rolling Stone. No. 565. 16 November 1989. p. 96.

- ^ "100 Greatest Albums Ever". Q. No. 137. February 1998. pp. 37–80.

- ^ "Elvis Costello: Imperial Bedroom – The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 1 November 2003. Archived from the original on 28 February 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Elvis Costello: Imperial Bedroom – The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ Larkin, Colin, ed. (2006). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). London: Virgin Books. p. 131. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ Dimery, Robert; Lydon, Michael (2018). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die (Revised and Updated ed.). London: Cassell. ISBN 978-1-78840-080-0.

- ^ a b Clayton-Lea 1999, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Hinton 1999, p. 437.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Imperial Bedroom [Rhino Bonus Disc] – Elvis Costello / Elvis Costello & the Attractions". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Imperial Bedroom [2015] – Elvis Costello / Elvis Costello & the Attractions". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ "Imperial Bedroom – Elvis Costello / Elvis Costello & the Attractions Album Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Clayton-Lea, Tony (1999). Elvis Costello: A Biography. London: Andre Deutsch Ltd. ISBN 978-0-233-99339-3.

- Costello, Elvis (2015). Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink. London: Viking Books. ISBN 978-0-241-00346-6.

- Gouldstone, David (1989). Elvis Costello: God's Comic. New York City: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-04309-4.

- Hinton, Brian (1999). Let Them All Talk: The Music of Elvis Costello. London: Sanctuary Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-86074-196-8.

- Parkyn, Geoff (1984). Elvis Costello: The Illustrated Disco/Biography. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-0531-2.

- Perone, James E. (2015). The Words and Music of Elvis Costello. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-1-44083-216-1.

- St. Michael, Mick (1986). Elvis Costello: An Illustrated Biography. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-0772-0.

- Thomson, Graeme (2004). Complicated Shadows: The Life and Music of Elvis Costello. Edinburgh: Canongate Books. ISBN 978-1-84195-796-8.

External links

[edit]- Imperial Bedroom at Discogs (list of releases)